-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “India’s French Connection: Indian Artists in France” at DAG, New York, 2018–19. All images courtesy DAG, New York.

The exhibition “India’s French Connection: Indian Artists in France” at DAG New York was a fitting sequel to “The Progressive Revolution: Modern Art for a New India,” which opened at Asia Society last September. While the latter focused on artistic efforts at articulating India’s post-Partition identity, DAG’s show highlighted the impact of international movements on this national project. Works by around 20 artists who had traveled from newly independent India to Paris from the 1950s to ’70s revealed the ongoing evolution of new forms and expressions that had been spearheaded in Mumbai by the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG), whose manifesto emphasized “absolute freedom for contents and technique.” Although the PAG disbanded in 1956, India’s cultural decolonization had already hit its stride. Experimental techniques commingling ancient Indian forms with brilliant Fauvist colors and expressionistic applications had appeared in the early works of PAG members such as SH Raza and Akbar Padamsee even before they traveled to Europe. But it was in Paris—long considered a crucible for nurturing avant-garde movements—where many important Indian artists, from modernists including Jehangir Sabavala to contemporary figures like Nalini Malani, crystallized the synchronicity between Eastern-inspired iconography and Western methodologies.

Training at Parisian art schools including the École des Beaux-Arts and at workshops like the printmaking studio Atelier 17, propelled innovative explorations of European techniques and styles. For example, under the tutelage of English printmaker Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17, Krishna Reddy invented the viscosity technique that enabled the simultaneous printing of numerous colors. This in turn resulted in key multicolored, early prints such as Two Forms in One (1954), which depicts an orange, cocoon-like structure amid crisscrossing lines and prefigures the complex matrices of intertwining, web-like grids for which Reddy is known. In Laxman Pai’s watercolors from 1956, images of foliage and a rural woman are subtly embedded amid speckled and twirling brushstrokes. Even in Jehangir Sabavala’s Icarus (1965), an oil painting of an ethereal yellow figure floating within a blue sky, the former’s multiple wing-like arms, unmistakably inspired by Cubism, give it a refreshingly modern sensibility.

An East-West synthesis was best seen in depictions of the female body at the show. Prodosh Dasgupta’s evocative granite sculpture Suryamukhi (1978) of a curvaceous, supine woman, suggesting both a sexual as well as birthing posture, is rooted in images of the Indian mother goddess Lajja Gauri, while also recalling the style of modern British sculptor Henry Moore’s figures. A similar fecundity radiates from the voluptuous, pomegranate-like breasts depicted in Prokash Karmakar’s Untitled (1975) painting of a nude female torso. Elsewhere, in early, untitled works by Nalini Malani, Anjolie Ela Menon, and Paritosh Sen, female figures become emblems of feminine power and independence. While Malani’s seated figure in her 1978 oil painting looks firmly away from the viewer, Menon’s more brazen, Modigliani-esque frontal nude from 1959 gazes unflinchingly outward. Likewise, Sen’s standing female form, painted in shades of walnut and pecan in thick expressionistic brushstrokes, embodies abstract notions of force and vigor.

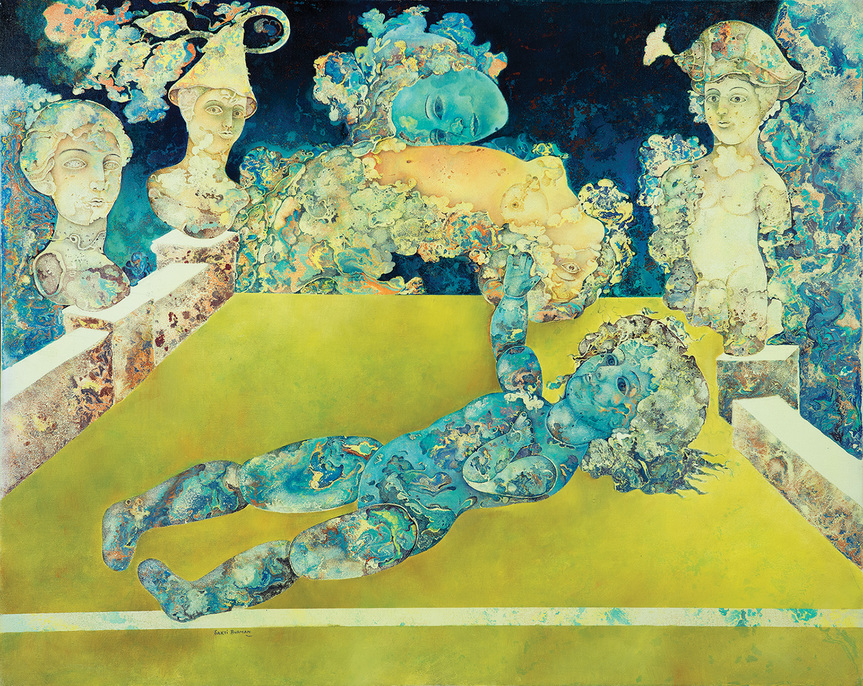

Although many of these artists returned to India, a few, notably Sakti Burman, SH Raza and Krishna Reddy, remained in Europe for decades and developed fluid abstract styles embedded in Eastern thought and representation. Raza’s early, vibrant landscapes evolved into his famous, tantric, mandala abstractions, and Burman’s 1973 painting Magie de poupée (Doll Magic) typifies his highly detailed, colorful canvases brimming with surreal visual references to Indian mythology. But none of these artists were ever included in French historical compendiums, and the acknowledgement of Indian modernism within Europe fell to the wayside.

Perhaps the most striking works in this newfound, Indian visual language are Himmat Shah’s black, painted terracotta heads made in 1982. These partly classical, partly primordial objects that defy neat aesthetic categorization represent a timeless contemporaneity. Far from what Western critics have termed as derivative, Shah’s sculptures, which evoke both Constantin Brancusi’s forms and traditional African masks, are nonetheless entrenched in the rugged style of Indian folk forms, and exemplify the plurality of an avant-garde movement that took shape in independent India.

“India’s French Connection: Indian Artists in France” is on view at DAG, New York, until April 8, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.