-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

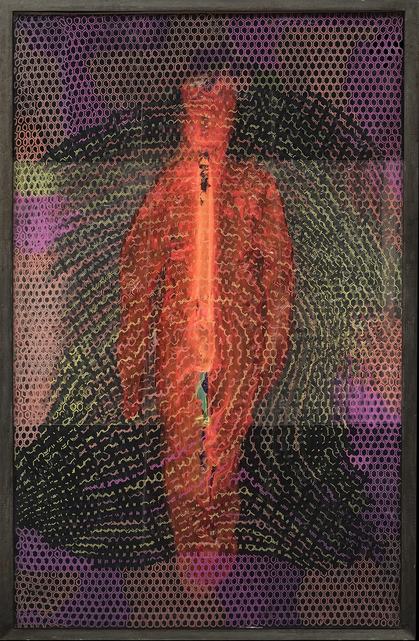

Installation view of KESANG LAMDARK’s “Knock, Knock” at Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Rossi & Rossi, London/Hong Kong.

“Knock, Knock,” Tibetan artist Kesang Lamdark’s first solo show at Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong, derived its title from the repetitive hammering needed to make the tiny holes on the surfaces of his light boxes and sculptures on display. Describing his technique, Lamdark compares the hammering to “the sounds of monks making a sand mandala,” a traditional Buddhist ceremony lasting up to several weeks that involves carefully tapping colored sand out of a copper tube to create a complex ritual diagram. Like the sand mandala ceremony, Lamdark’s artmaking is a meditative process, which he uses to express his displaced identity, and to understand Tibetan culture and its transformation.

KESANG LAMDARK, H. H. in da House, 2018, glass mirror with LED lights and wood, 70 × 200 × 8 cm. Courtesy the artist and Rossi & Rossi, London/Hong Kong.

Born in exile in Dharamsala, India, Lamdark received a Western upbringing after being accepted as a refugee in Switzerland. The topic of exile is explored in H. H. in da House (2018), a large light box made of a perforated, mirrored panel immediately visible upon entering the exhibition, showcasing a frontal view of Lhasa’s Potala Palace, a historic residence of Tibet’s spiritual leaders until the current Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959. At the center of the panel is a portrait of the exiled Dalai Lama on the palace’s central exterior wall, reminiscent of Mao Zedong’s picture in Tiananmen Square, illustrating the dream of many Tibetans: His Holiness returning to an independent Tibet as the head of state.Despite the reverence embedded in this vision, upon closer inspection of the work, one can spot a man snorting cocaine at the bottom. The panel itself is, in fact, made from cheap IKEA mirrors. The juxtaposition of Tibetan spirituality with hedonism and bland, mass-produced objects—both often associated with Western capitalist society—demonstrates Lamdark’s straddling of cultures, and raises questions of how an imported consumerism is affecting Tibetan society.

KESANG LAMDARK, Drunk Driving in Lhasa, 2017, perforated beer cans, car screen, PVC and lights on wooden table, 124 × 148 × 72 cm. Courtesy the artist and Rossi & Rossi, London/Hong Kong.

Beer—particularly the local Lhasa Beer brand, produced predominantly for Chinese consumption—figured prominently in “Knock, Knock,” a symbol of the consumer forces impacting Tibet. In Drunk Driving in Lhasa (2017), an installation evoking the aftermath of a car crash, 46 perforated beer cans protrude from a cracked windscreen, surrounded by disco lights, alternately flashing red, orange, pink, and bright green, like a multicolored fire. The wreckage displays the assault on Tibet’s traditional religious values by an influx of foreigners and the attendant commercialization of Tibetan heritage, yet the tragedy of this cultural erosion is tempered by Lamdark’s playful and sometimes crude sense of humor. Viewers are encouraged to peer into the cans like they would kaleidoscopes, with the color-changing lights illuminating the different micro-pointillist images at the bottom of each can, from depictions of religious figures to a woman performing fellatio, a skeleton cartoon and the American band The Blues Brothers. Here, the deadly collision of religion, sex, and Western culture suggests the fall of the barrier that had shielded Tibet from harmful outside influences. While Tibet was once isolated by its religion and geographical inaccessibility, its mystified otherness and Chinese government-led economic development have made the region a prime target for travel and business.

Death and destruction culminate in the installation Illuminati (2018), in which a blacklight illuminates a bright orange figure resembling a burning corpse, referencing the self-immolation of Tibetans fighting for their region’s independence. The work is a clear echo of Lamdark’s earlier piece, Fire-Proof Suit Over Palden Choetso (2013), comprising a gold-colored PVC suit on black plastic netting, set over an image of the eponymous nun who self-immolated in 2011 as a gesture of protection. In Illuminati, Lamdark placed his fingerprints all over the transparent plastic wrap covering the figure, an assertion of identity to make up for the loss of visible individualizing markers after burning.

In establishing clear oppositions that characterize Tibet’s current sociopolitical dilemmas, as well as the cultural space he inhabits as a Tibetan-Western artist, Lamdark offers no conclusive insights as to their possible reconciliation, often opting instead for surprising and witty commentary. Yet, the process of working through these complexities was perhaps the point of “Knock, Knock,” with the title alluding not only to a meditative ritual, but also to a request for entry, a point from which to begin.

Kesang Lamdark’s “Knock, Knock” is on view at Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong, until November 24, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.