-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of MAX PENSON’s “Light on Central Asia” at Andakulova Gallery, Dubai, 2017. Courtesy Andakulova Gallery.

As the photographic image continues to mutate into filtered and cartoonish forms, the time is ripe to consider the pioneering work of those who steered photojournalism toward its current aesthetic form. Max Penson (1893–1959) was born in Belarus and educated in Vilnius, Lithuania, but he found his muse after moving to the Fergana district of eastern Uzbekistan as a young man. This was a time when Uzbekistan was beginning to transition from a feudal community to a modern society after the Russian Revolution of 1917. In Fergana, Penson worked as a drafting teacher; at the age of 28, the district gifted him a camera. Now with a tool with which to capture his muse, he set out to record the changing landscape and denizens of Uzbekistan.

Penson relocated to the capital city Tashkent to work for the Pravda Vostoka newspaper from 1926 to 1949, which at the time had the widest circulation in Central Asia. He trained his Leica camera on the people, landscape, architecture and customs of Uzbekistan. By 1940, he had taken over 30,000 photographs, and his images were widely distributed across the USSR, gaining him notoriety as a photojournalist and eventually fame as one of the fathers of Russian avant-garde photography, culminating in his Grand Prize at the 1937 Universal Exhibition in Paris for his Uzbek Madonna, a portrait of a young woman nursing her child. Coinciding with the centennial of the Russian Revolution, his work was shown in the “Light on Central Asia” exhibition at Dubai’s Andakulova Gallery with support from the Consulate General of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

In viewing the artworks, Penson’s mastery of light and shadow is evident. His subjects are raw and authentic. He records Uzbek daily life at a time when traditional feudal life was transitioning to industrial modernity. In the artist’s eyes, seemingly mundane events can be both intimate and monumental—in At Smelting Furnace (1950), the silhouette of a man is backlit by a shower of glowing sparks as he toils in a smelting plant; in another image where the light source is behind Penson’s subject, On a Cart (1939), the contrast between the sharp outline of a peasant on a horse cart and the hazy sunlight gives the image the air of another world. Penson’s mastery of light and contrast is also revealed through his portraits of individuals—in School Girls (1925), an image of two young girls illuminated by a sunbeam, and Artist (1940), a photograph of a man painting a wooden column with his face tilted slightly upward, Penson’s virtuosity as an artist is revealed by the delicate contouring obtained in his captured moments.

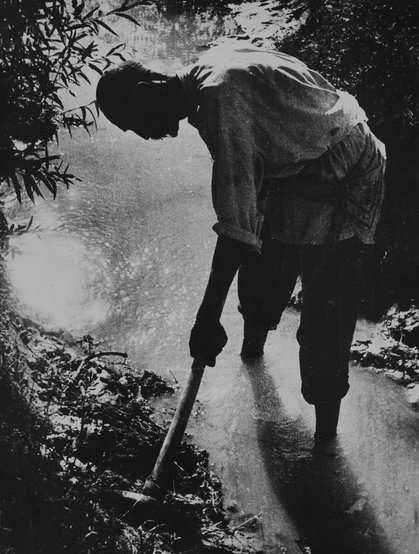

The photographer also explored labor in his work, featuring the people who were responsible for the extraordinary transformation of Uzbekistan during the first half of the 20th century, and the transition from peasant labor to industrial labor instituted by the Soviet Union. The photograph A Mirab (1940) is particularly arresting: a proud figure is, again, silhouetted against the sunlight, ankle deep in an irrigation canal and gripping a hoe, his back bent with effort and strain, conveying the struggle of the peasant laborers of Uzbekistan. In contrast to this is the Soviet-realist style image Repairs to Excavator (1939), in which we see a man perched proudly on a steel-beam arm, dwarfed by the giant cogs of the machine. In Desert Sands (1937), a man peers at the horizon from the crest of a sand dune, dressed as an icon of the modernity that Penson so meticulously documented.

Penson’s photographs function in many ways—as art, as photojournalism, and as anthropology. The images are gorgeous and intimate; Penson’s affinity for human connection is clear in his ability to draw emotion out of his subjects. This is where he is a photojournalist and anthropologist, as he provides a detailed account of the lives of many individuals in the throes of a massive shift. From the images, it is clear that the process is a collaboration between Penson and his subjects. Aesthetically, it is a reminder of the artistry in photography, a stark contrast to our era, when image manipulation is the norm. Using only his eyes and camera, Penson was able to extract from real life what so many coders still fail to capture in myriad smartphone applications and photo-editing software—true, unfiltered experiences, in all of its complicated and devastating beauty.

Max Penson’s “Light on Central Asia” is on view at Andakulova Gallery, Dubai, until December 6, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.