-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

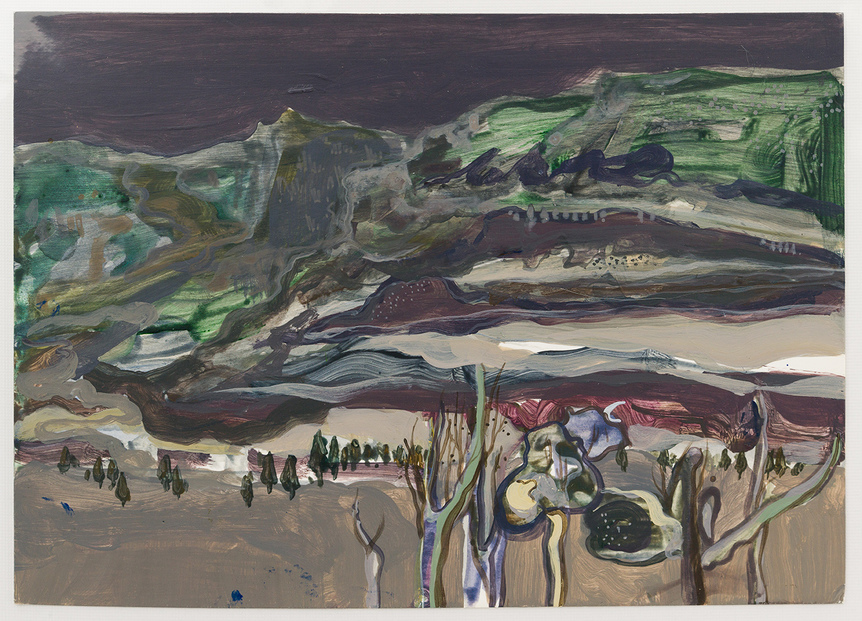

Installation view of LIN SHAN’s “Living Room” at ShanghArt M50 Gallery, Shanghai, 2018. All images courtesy the artist and ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai / Beijing / Singapore.

ShanghArt’s gallery at M50 is an awkward shape, on a mezzanine with a high celling, accessed via concrete stairs—there is nothing remotely homely about it. Under subdued lighting, Lin Shan’s “Living Room” represented less a place than an uneasy atmosphere.

A pair of tableaux establish the forlorn ambiance of mismatched heirlooms and faded photos. Drawn into a corner, two threadbare upholstered chairs are set beside a tall plant stand and a tiny round table. Stood on a moss-colored fibrous material, covering the floor like a deep mold, these items act as a set for Memory Wall (all works 2018 unless noted). Looking predominantly like family portraits depicting twins or huddles of siblings, the tiny paintings arranged on the wall are often little more than shadowy outlines. These hang alongside a few objets trouvés, as might be rescued from abandoned buildings, such as scraps of lace and tarnished metal. Rather than drawn together to invite intimacy, the chairs

are set square to the wall, as in a cold waiting room.

Arranged beside a stark concrete pillar, the second tableau is like the setting of a séance in a horror movie. A house plant, dwarfed in the space, does little to inject life into the scene. Four cushions lie on a crimson rug, while a low round table is covered in a Victorian lace cloth and set with a reproduction lamp. The ensemble acts as the mise-en-scène for Album (2016–18) and Music Box No. 2. Ominous tinkling music, implicitly emanating from the latter, is amplified on a speaker under the table. The little box, hand-painted in gray and decorated with mauve polka dots, has under its lid two faceless portraits. They recall 16th century Flemish miniatures, and are like ancestors whose identities have been lost. A rather tawdry photo album placed on the table tempts the visitor to browse through vague and murky paintings, like impressions of remembered places: forests, marshes, parks, a fairground, the barred door of a prison—all desolate. The provenance of the images is elusive; they are mementos not of individuals but of the interconnected in a global network, in which the stories and images

of many lives are shared, and it becomes impractical to verify the continuity of every narrative. Truth is more a question of feel than exactitude.

Across the walls of the gallery, groups of uncanny and faceless portraits appear to have leached their muted hues from the gray concrete floor. The poses, backgrounds and empty features are reminiscent of August Sander’s exhaustive photographic taxonomy of the German people. Sander’s nameless subjects are regarded with cold objectivity by his camera, each of them representing an archetype, for example,

a police officer or high school student. Lin’s portraits are similarly generic, but stripped down to present not even types of people, just types

of image.

Several, such as Gemination No. 10, Untitled Nos. 3 and 7, adapt the prototype established in one of Sander’s most poignant images, My Wife in Joy and Sorrow (1911), portraying a woman in mourning, her expression drained with grief. She cradles twin babies, one living, the other dead. The image of twins proliferates in the exhibition, suggesting alternate outcomes from a common beginning.

Lin’s Twins On The Sofa and Twins On The Sofa (Mirror Image) look like they are copied from a black and white photograph. Two children sit close together, their elbows touching but their downturned faces gazing in opposite directions. The companion painting is both mirror and negative image. In the analog photographic process, the unworldly negative representation comes first; it is the original record from which positive copies can be made. When the negative is destroyed, it ends the line of alternate reproductions. Grouped together, several works, Untitled Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, and Starry Night Nos. 2 and 4 mitigate this possible tragedy by highlighting the homogeneous nature of the idiom of family photo. If one cozy image of childhood is lost, there are multiple variations that may take their place.

The dingy gallery exposed the milieu of an anonymous family with roots torn apart—a “living room” for visitors who seek authenticity without candor; the displaced who are willing to associate with any adoptive family. Their own memories cannot be confirmed. Their images circulate. Their origins are vague, their pasts split and shattered.

Lin Shan’s “Living Room” is on view at ShanghArt M50, Shanghai, until June 24, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.