-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of MUSQUIQUI CHIHYING’s solo exhibtion at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2018. Courtesy Ullens Center for Contemporary Art.

I’m told that the dual occurrence of Musquiqui Chihying’s first solo exhibition in mainland China and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation was a coincidence, but it’s a fortunate one as the triennial meeting of African and Chinese leaders is representative of the same relationship that the artist explores in his exhibition at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA). A boom in Chinese government-led investment in Africa over the past decade—though resulting in demonstrable improvements in infrastructure in parts of the continent—has stoked global fears of Chinese neo-colonialism. Chihying’s exhibition examined how this rise in Chinese power might influence the reception, production, study and exhibition of African art objects and of aesthetics more generally, an innovative topic that, nonetheless, offered more questions than answers.

The Sculpture (2018), one of the exhibition’s three videos, begins with footage from 2017 of French president Emmanuel Macron announcing his commitment to the restitution of French-held African objects looted during the colonial era, contextualizing the exhibition’s exploration of Sino-African relations within historical European imperialism. The double-channel video, featuring Chihying’s narrative voice layered over archival images and videos, elaborates on how so many African artifacts ended up in European museums, before bringing us back to the present with an account of the collecting habits of Xie Yanshen, a Chinese philanthropist with a penchant for African art who has donated some 5,000 items to the National Museum of China, and who serves as director of his private International Museum of African Art in Lomé, Togo. In the final minutes of the video, we find Chihying playing the role of a young Xie, dressed in a smart suit, surveying photographs of artworks. In this staged photograph, Chihying apes a well-known image of the art theorist André Malraux standing over numerous photographs of artworks, a visualization of Malraux’s idea of the “Imaginary Museum.” This referred to the ways in which, beginning in the 20th century, newly profitable juxtapositions between disparate artworks—enabled, in particular, by rising globalization and the advent of photography—divorced them from their original cultural, geographical and historical contexts, allowing them to be abstract entities in art history. Chihying’s refashioning questions how aesthetic dynamics might be altered if the historically European power of selection is replaced with Chinese control.

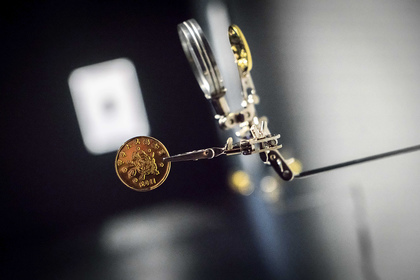

For The Cultural Center (2018), an installation comprising coins suspended in the air by sets of spindly metal arms protruding from the wall, Chihying took inspiration from the discovery of Chinese Ming-era currency in Kenya, which has been positioned as counter-evidence to the dominant narrative of Ming-dynasty isolationism—something hinted at in The Sculpture, in which Ming naval commander Zheng He’s contact with Africa is also mentioned. Chihying gives this historical moment a contemporary interpretation through the bright, gold reimagining of the original coins, refashioned to depict African museums and theaters built by Chinese companies in the 21st century. While Chihying refrains from explicitly framing these building projects as either positive or negative, there is something disconcerting about ostensibly Chinese coins depicting structures in African countries, considering currency often incorporates symbols of specifically national achievement in its design.

Installation view of MUSQUIQUI CHIHYING’s The Guestbook, 2018, single-channel HD video: 14 min 43 sec.., at “Musquiqui Chihying,” Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2018. Courtesy Ullens Center for Contemporary Art.

The Guestbook (2018), another video work at the show, is a short, slow-paced, black-and-white movie marked by some beautiful static shots of Berlin. The book in question—a thin, battered copy that Do Do, the Togolese protagonist of the film, finds in Berlin’s State Library—is filled with the signatures of colonial-era explorers. The plot follows Do Do as he seeks out two other locations for no discernible reason: Treptower Park, where the German Colonial Exhibition was held in 1896, and a Chinese massage parlor that used to be a Chinese restaurant called Nanjing, where Zhou Enlai, a key figure in improving Sino-African relations, was said to be a regular attendee. Many of the names and locations in this ambiguous, fictional story also appear in the more academic, lecture-style video, The Sculpture. Yet, neither of these approaches extends far beyond presenting Chihying’s research. The future-oriented focus of the exhibition goes some way towards justifying the preponderance of observations and questions rather than incisive conjecture, but without a more comprehensive evaluation of the potential realities of a Sinocentric future for Africa, its art, and aesthetics in general, the exhibition lacked a powerful sense of conclusion.

Tom Mouna is ArtAsiaPacific’s Beijing desk editor.

Musquiqui Chihying’s solo exhibition is on view at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, until October 28, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.