-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

TUAN ANDREW NGUYEN, My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires (still), 2017, two-channel video installation, 1080p, color, sound: 18 min 51 sec. All images courtesy the artist and 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong, unless otherwise stated.

I’ve always looked upon the Christian rite of consuming Christ’s body and blood, taken quite literally in Catholicism, with a degree of squeamishness. The logic of eating that which you worship indicates (at least, to this heretic) that the path from pious to base is a short one. The disturbing paradoxes within humanity’s belief systems, mythologies and obsessive patterns of consumption—and the actual destruction this wreaks on our planet—are at the heart of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s incisive solo exhibition, “My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires,” which was executed with conviction, clarity and a hefty dose of black humor.

Nguyen’s investigations into extinction, culture and consumerism began when the artist came across an article on Vietnam’s last Javan rhino, found dead after a poacher hacked off its horn. Rhino horn is wrongly believed to have special properties in traditional Chinese medicine, and is now a luxury product. Nguyen captures the tragedy of such misguided superstition in The Wrath of Imagination (2018), a beautifully embroidered rendering of Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 rhinoceros woodcut, which inaccurately depicts the animal as a scaly, armored beast. Vietnamese script embroidered above the image recounts a fictional meeting between a hunter and a rhino shortly before its death, who tells the man that he was “an artist who drew a rhino from his imagination and since has kept reincarnating as a rhino.” We may smirk at past folly, Nguyen seems to say, but the human imagination has always been precariously balanced between the wondrous and the monstrous.

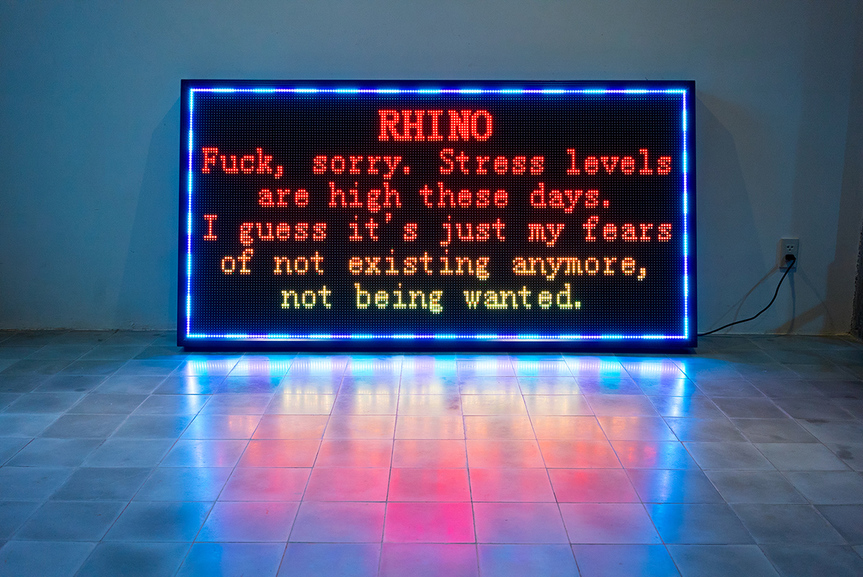

The paradoxical extremes of idolatry and slaughter that characterize humanity’s relationship to animals is encapsulated in The Irony of Our Worship / The Revolutionary Reincarnated As A Pangolin (2017), an installation in the style of a Vietnamese ancestral shrine with pink, plastic flowers and shiny trinkets galore, illuminated by garish LEDs and neon. A figure of a pangolin—endangered due to demand for its meat and scales, which in China and Vietnam are a delicacy, also believed to cure ailments—stands stoically on the plinth, clutching a red poster emblazoned with the words “death before extinction” in Vietnamese, a line that sits comfortably in the communist propaganda handbook but dips into absurdity coming from a pangolin imbibed with the revolutionary spirit. Reading Irony in dialogue with The Warning (2017), a storefront LED sign playing a looped conversation between a pangolin, a dragon and an emotionally vulnerable rhino, we begin to see Nguyen’s analysis of the connection between worship and consumerism take shape. Using tacky visual cues that one would see on a typical high street, he points out the dangers of characterizing this culturally-rooted desire for “magical” animal parts as anything other than base consumption: insofar as these beliefs and practices satisfy our need for fulfillment, prosperity and salvation, then they are also a form of consumption, taken to a literal extreme in the context of eating other creatures to extinction.

Yet Nguyen stops short of lambasting culture even as he coolly critiques its excesses. His undidactic approach can be seen in show’s eponymous two-channel film, the voiceover narration of which involves the spirits of the last Javan rhino and the Hoàn Kiếm turtle Cụ Rùa engaging in a Socratic debate on the liberation of animals from mankind. Employing the revolutionary language of figures like Fidel Castro, the rhino spirit bitterly recounts the suffering inflicted on animals by their human oppressors, powerfully underscored by nauseating shots of animal carcasses and nonchalant butchery. The juxtaposition of animal skeletons, sculptures and effigies—including, in a particularly enchanting, oneiric sequence, Nguyen’s bamboo Rhino Spirit Costume (2017), worn in a ritualistic dance in the lush Vietnam jungle—with live creatures, often in varying states of distress, is another reminder of “the irony of our worship.” Cụ Rùa interjects with empathetic references to the ways that culture has sustained the Vietnamese through their own suffering, in times of colonialism and war, and later speaks of a prince who sacrificed himself to save a starving tiger and was reincarnated as a deity for his benevolent deeds. This alternate viewpoint indicates Nguyen’s refusal to reduce or erase culture, suggesting instead a shift toward other beliefs—such as the show’s recurring themes of karma and reincarnation. As the mesmerizing final shot ascends above the canopy of the sprawling forest, Cụ Rùa asks her rhino interlocutor: “After a cycle of karma, who will you become?” We are left with no answer, no cathartic release; just the uneasy feeling that the question could just as easily be directed at us.

Ophelia Lai is the reviews editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires” is on view at 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong, until August 18, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.