-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

The most comprehensive exhibition of modern and contemporary Nepalese art ever assembled outside of the country’s borders, “Nepal Art Now” at Weltmuseum Wien, was an extraordinary organizational achievement. Featuring around 130 works, spanning painting, sculpture, video and installation, by approximately 40 Nepalese artists, the exhibition showcased the country’s art of the past 60 years, from the nascent modernism of the 1950s following the overthrow of Nepal’s Rana dynasty to more recent trends that engage with postmodernism, censorship, feminism, and ecological disasters.

With four years of planning behind an exhibition of this scale, scope, and ambition, the result was both bewitching and bewildering. The complex symbolic references, with their blending of Hindu and Buddhist iconographies, Nepalese customs, traditions, histories, and cultural points of reference, all pose certain interpretive challenges for Western audiences. To its credit, the museum invited the artists and, when impractical or impossible, Nepalese curators to write descriptions of the works in an attempt to ameliorate the issue of ceding “interpretational sovereignty of the works” to Western curators, as the catalogue explains.

A number of the exhibition’s most striking works examine gender politics and the status of women in Nepalese society. Two paintings by Manish Harijan, Marilyn – Kali (2017) and The Kali – Odalisque (2016), merge the imagery of Andy Warhol’s 1967 “Marilyn Monroe” screenprints and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 1814 Grande Odalisque with the iconography of the Hindu goddess Kali, creating an unorthodox clash of Nepali spiritual practices and Western art history that simultaneously seduces and repels through its exploration of cultural representations of female beauty. In Sheelasha Rajbhandari’s Agony of the New Bed (2016, from the series “Marriage Taboos”), the faces of 32 women on miniature marital beds are overwritten by stitched text or decorative imagery, convey how the women’s individuality, freedom, and control over their reproductive rights are effectively silenced as a result of marriage. Working within the paubha style (a traditional type of devotional Buddhist painting in Nepal), Mukti Singh Thapa combines a formal, traditional visual language with pointed commentary on infanticide, violence against women, and the impacts of male desire in three beautifully ornate images, Mayadevi (2013), Mother (2014), and Purush (2015), respectively.

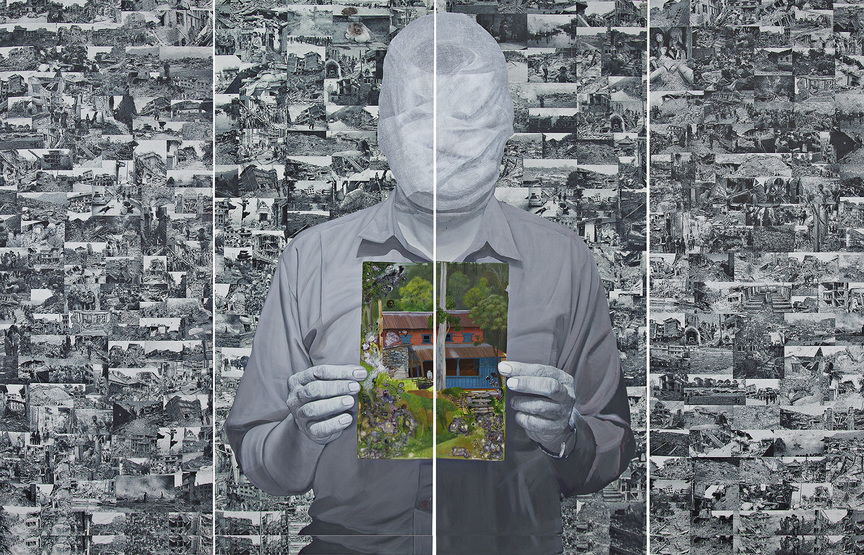

Given Nepal’s recent history, another significant thematic strand focused on war and environmental disaster. On April 25, 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake killed over 9,000 people, injuring more than 23,000 and displacing more than 2.8 million people; Hit Man Gurung’s large-scale canvas We are in war without enemies (2016) critically engages with the widespread political corruption that stymied relief efforts after the earthquake. In the foreground, a man with a bandaged face holds a picture of his home before the disaster, while the background features stacked black-and-white images of the ensuing wreckage. In another canvas, The Revolutionary Dreams (2018), Gurung addresses the economic impact of conflict by portraying himself in two types of uniforms, the camouflage of Nepal’s People’s Liberation Army—established by Maoist insurgents during the Nepalese Civil War (1996–2006)—and the blue workers’ suits that many ex-PLA soldiers would subsequently wear as cheap foreign laborers in the Gulf and Malaysia following their emigration.

For all of the highly informed and informative Nepalese voices that emerged in the exhibition, the museum’s ostensible relinquishment of its own curatorial voice nevertheless illustrated the inherent power imbalances in such “East-meets-West” projects, in which Western institutions in a sense legitimize “Eastern” art through its very inclusion in contemporary art discourses. The point is not to speak of Kathmandu as a center of art alongside Paris, London, and New York, as Weltmuseum director Christian Schicklgruber does, but rather to recognize that such a globalizing process of disembedding Nepalese art is not without its consequences for the artists, visitors, and institutions. When decontextualized in this way, Nepalese art can become more episodic, transient, and market-oriented. Without the requisite cultural fluency, Western audiences can revert to a Eurocentric engagement that understands “Asian” art as part of, rather than distinct from, Western art traditions. And in the absence of alternative terminologies, institutions can mistake words such as “modernity” for a universal language or style. In his 1932 essay “About Corot,” Paul Valéry wrote, “One must always apologize for talking about painting.” The same might be said when talking about such transcultural projects.

“Nepal Art Now: Contemporary Nepalese Art” is on view at Weltmuseum Wien until November 6, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.