-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

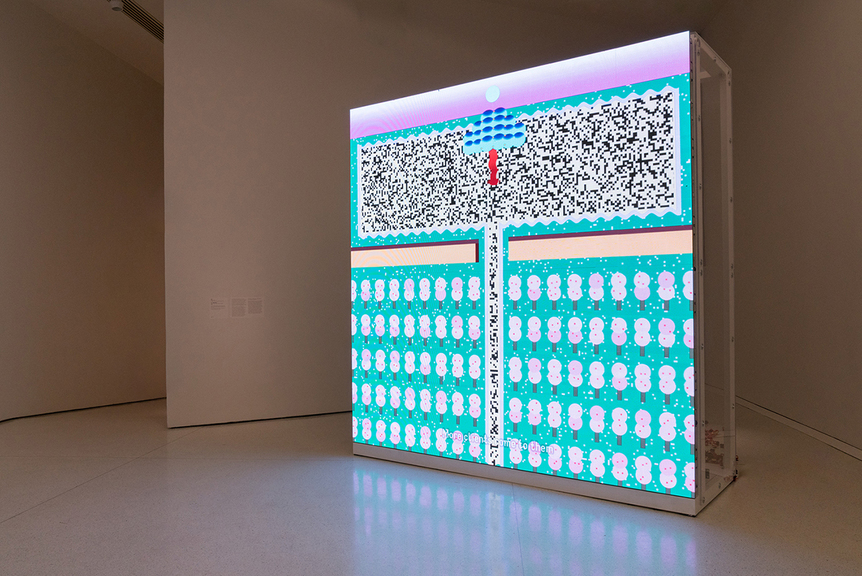

Installation view of CAO FEI’s Asia One, 2018, multichannel video installation, color, sound, dimensions variable, at “One Hand Clapping,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo and copyright David Heald. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

In Beijing-artist Cao Fei’s speculative fiction film Asia One (2018), a group of time travelers from the future descend upon an abandoned warehouse. They peer at the dusty conveyer belts, no doubt wondering what sort of primitive people once operated them. Then the video cuts back to the present: an automated distribution center complete with robots and AI technology whirs to life. This depiction of one of the world’s most advanced, unmanned industrial facilities located in China serves a startling reminder that the future has already arrived.

Asia One came to New York as part of “One Hand Clapping,” the third exhibition highlighting Chinese artists to open at the Guggenheim in the past three years. While “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World,” staged last year, offered an ambitious overview of the Chinese contemporary art movement, “One Hand Clapping” provided a more focused examination of the current Chinese experience. Curator Xiaoyu Weng and consulting curator Hou Hanru borrowed the title from a Zen Buddhist riddle, or koan, that asks, “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” In response, five artists from China and Hong Kong—Cao Fei, Duan Jianyu, Lin Yilin, Wong Ping and Samson Young—explore cultural identity and modernity through the lens of globalization and technology.

CAO FEI, Asia One, 2018, still from multichannel video installation, color, sound, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Effectively conveying dystopian feelings of alienation and futility, Cao’s dizzying take on the legacy of the Cultural Revolution centers around JD.com, a global e-commerce company known as the “Amazon of China.” Asia One follows an employee who spends more time interfacing with digital devices than he does human beings. From time to time, he encounters the one other person working there. But even in their isolation, there’s little sense of privacy, as the robots trailing behind analyze and evaluate their every move. Appearing like a fever dream, a scene, in which a group of workers stage a dance performance reminiscent of revolutionary operas, contrasts the lack of actual manpower needed to run the sorting facility. The encompassing multimedia installation drives home the film’s sense of irony, with multicolored banners aimed at encouraging productivity. “Humans and machines, hand in hand,” reads one of them, mounted on the

wall above a motorized delivery tricycle.

Guangzhou-artist Duan likewise recalls nationalist sentiment to ironic effect in her series of oil paintings, “Spring River in the Flower Moon Night” (2017–18), juxtaposing familiar imagery that’s often marshalled out as examples of “authentic” Chinese culture, such as the fabled Moon Lady and musicians playing classical instruments, with that of disabled street beggars. The figures painted in muddy colors with shadows obscuring their faces represent those who have not benefited from China’s rapid economic growth and urbanization efforts. Duan further undercuts notions of authenticity in cultural mythmaking with anthropomorphized carrots, as seen in Picnic 1 and Picnic 2 (both 2018). The bronze sculptures painted in bright orange and green acrylic, and positioned as if lounging around a basket, reference not traditional folklore but a recent internet meme.

Lin, an immigrant artist who lives in Beijing and New York, worked with NBA star Jeremy Lin on his VR experience The First 1/3 Monad (2018), in which the viewer assumes the perspective of the ball. The confusion of one’s subjectivity—with the viewer as the object, while Lin is given agency—becomes a moment of reversal, especially considering how the Chinese-American athlete is often othered by the media in his home country. Yet, as someone who’s instantly recognizable to Chinese and American fans alike, his outlandish hair unmissable in the 3D rendering, the basketball

icon also represents a cross-cultural phenomenon.

The question of how we relate—or fail to relate—to each other in the modern age underlines the work of Hong Kong-born Wong, the sole millennial of the group. His tragicomic animation, Dear, Can I Give You a Hand? (2018), tells the surreal story of an aging widower who’s more attached to porn than he is to his immediate family. Meanwhile, Young, a fellow Hong Kong native and trained composer, pushes the possibilities of what is “real” in the musical realm. In collaboration with the University of Edinburgh’s Next Generation Sound Synthesis (NESS) project, he simulated instruments that physically could not exist in the real world, such as a trumpet that is 20 feet long, and another that can only be blown by 300-degrees-Celsius breath. Using these “impossible trumpets,” he composed the musical arrangements heard in the sound installation Possible Music #1 (2018).

Though sometimes absurd or darkly humorous, the futuristic visions in “One Hand Clapping” did not succumb entirely to cynicism. In exploring missed connections or the possibilities

of artmaking, the works reaffirm the need for empathy and understanding—a sentiment reflected in our present moment.

And only by breaking down cultural narratives can the artists establish new relationships to their past and future, and contemplate new ways to be Chinese.

Mimi Wong is the New York desk editor for ArtAsiaPacific.

“One Hand Clapping” is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, until October 21, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.