-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

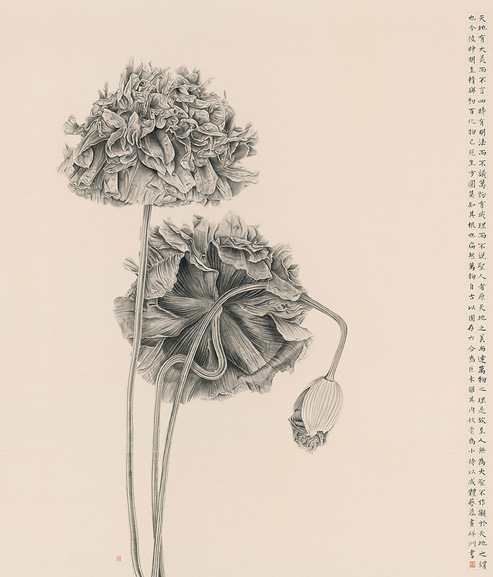

Chinese ink painter Tai Xiangzhou’s Flowing Clouds and Mighty Clouds (both 2017) primed the exhibition “One with the Universe,” which was jointly presented with fellow artist and spouse Zhang Yirong at Hong Kong’s Alisan Fine Arts. Behind the shifting mists depicted in the commanding, 198-centimeter-tall diptych, I caught a glimpse of what was perhaps a mountain peak, or a collection of islands. For the most part, however, Tai’s scenes escaped identification, evoking impressions of magma or oil slicks—the physical world—but also more ethereal planes and dreams. This was very much not the case with the two paintings of flowers flanking Tai’s works. Zhang inserted painstaking details into Poppies and Three Noblemen (both 2017), which looked as though they were pulled from the field notes of a natural scientist. This juxtaposition of amorphous forms and realistic portrayals was a cornerstone of the Beijing-based duo’s exhibition, which featured creations of ink on either paper or silk, but to radically different effect.

Zhang and Tai’s backgrounds are in equal parts esoteric and traditional. Both studied under renowned artists when they were younger—Tai under calligrapher and painter Hu Gongshi from when he was seven years old, and Zhang under contemporary ink artist Liu Dan after she completed her university studies. Tai initially studied and worked in media design, but ultimately decided to return to painting, completing a PhD in the medium in Beijing. Their work draws on the Song Dynasty literati school—where literal representation of a landscape is less important than the personal, subjective expression of its essence—as well as Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi’s proposal that all living things are equal, or that we are all one with the universe.

All of the exhibited black-and-white pieces were created in 2014 or later. Visitors can lose themselves in the swirling shapes of Tai’s The Existence of Clear Forms (2017), only to be confronted with more of Zhang’s blown-up petals and leaves in Picking Chrysanthemums Under the Eastern Fence (2017). If Tai presented an overarching, bird’s eye view of the world, the perspective that Zhang’s delicately rendered works offered was that of a magnifying glass. Neither artist adhered to the traditional motifs of Chinese landscape ink painting. In particular, Zhang has achieved such mastery over the ink brush that her paintings looked as though they were created with fine pencil or, in the cases of Butterfly 2014-7 (2014) and Butterfly Adrift Lakes and Hills (2017), with charcoal.

Tai’s works were so mysterious that they left me questioning whether I was looking at his interpretation of a particular landscape, or at arrangements plucked from his imaginings. The titles of his pieces—The Dragon’s Fiery Prance, Eternal Cycles (both 2017), A Song of Swirling Thoughts (2016)—provided no aid in solving the puzzle. Likewise, the more I appraised Zhang’s pieces, the more foreign her depictions of flora and fauna appeared. Indeed, how often does one examine a flower from stem to stamen? How familiar are we, exactly, with the workings of the minute universe of plants and insects?

In Tai’s Everlasting Nature (2017), the Chinese calligraphy running down one side explains how everything in the natural world contributes to the existence of heaven. While either Tai or Zhang’s works would have been thought-provoking on their own, together they present a sublime study of the world humanity inhabits along with innumerous other living beings.

Tai Xiangzhou and Zhang Yirong’s “One with the Universe” is on view at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, until October 21, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.