-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Pale Sentinels” at Aicon Gallery, New York, 2018. All images courtesy Aicon Gallery, New York.

Curated by the artist and activist Salima Hashmi, this group exhibition gathers an intergenerational set of artists from India and Pakistan whose works consider the violence of the 1947 Partition and its lasting effects. The exhibition’s title derives from the poem “A Prison Morning,” by the poet—and the curator’s father—Faiz Ahmed Faiz, which describes the sensorial elements of daybreak in a jail cell: the sounds of keys turning in locks, the weary looks of guards and captives, and the worn-out visage of the pale sentinel, who watches over the bloody histories between borders.

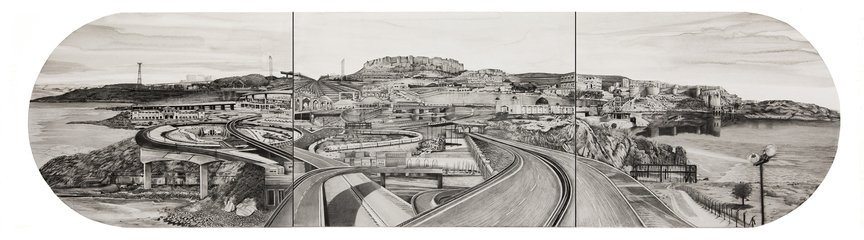

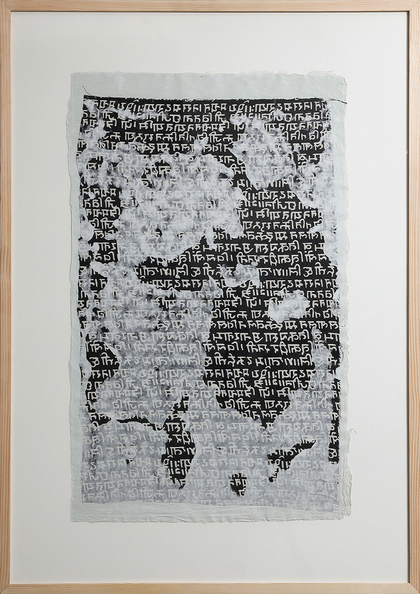

Spanning painting, ceramics, sculpture and drawing, the works in the exhibition track a sort of exhaustion as well, in their formal composition and materiality. Monochromatic graphite works by Saba Qizilbash depict landscapes in Northern India and Pakistan cut through by roads, bridges and railroad tracks; their industrial subject matter and washed surfaces confer on the exhibition an indication of both the physical landscape that was split apart by Partition and also indexes this land’s promise of economic output. In a similar monochromatic register, Waqas Khan’s works on paper, intricately detailed in ink with delicate, detailed markings that from a distance recall fingerprints, assert that these physical landscapes are dotted with individual experiences gathered as collective histories. Ghulam Mohammad’s triptych, Yaad Dasht (2018), uses unnamed family photographs as a background for laser-cut Urdu text to a chilling effect: slicing through nostalgia, the artist offers instead the gaps left by Partition’s separation. Indeed, these works, in their intricacy and austerity, highlight the exhibition’s insistence that the notion of remembrance—of memory as a fickle, slippery entity from which history emerges—is as much a processual and personal project as it is a collective imperative.

If the Radcliffe Line worked to split apart former lands and the bodies that inhabited them, the exhibition offers a series of works focused on mending or repairing these fault lines through their materiality, specifically their unified use of thread and fabric. Shilpa Gupta’s 1:2138 (2017) is a ball of shredded fabric from Bengali jamdani saris, which are handmade on looms in Bangladesh and, because of their demand in the Indian market, transported across borders by foot and eventually to larger Indian cities such as Kolkata and Mumbai. In her dematerialization of the sari to its material components, Gupta blurs the boundaries between nationalist products: what claim does the shredded ball of fabric have to Bangladesh, to India, or to anywhere in between?

These questions are further addressed by Priya Ravish Mehra, whose work anchors the show with its richly textured surfaces, providing an abstracted landscape in which to consider the multivariate meanings of borders, both conceptual and physical. The exhibition is in part a eulogy of Mehra—the artist passed away shortly before the show’s opening. Long associated with the practice of rafoogari, the traditional South Asian practice of darning and mending cloths to prolong their use, Mehra’s untitled works combine pashminas, cotton fabrics, jute, and paper pulp in dull, muted, matte tones interspersed with patches of bright colors. In the “Invisible/Visible” series, white paper pulp is placed on textile printed with barely legible, archaic Hindi; history as it is written is obscured, occluded and, ultimately, illegible.

What hope is there, then, for consolation, and what remains for the nation-state? “Pale Sentinels” does not suggest that the violence of Partition can be rectified through its representation, but offers the potential for the legacies of colonialism’s thrust to be understood from many angles. Hanging from the ceiling of the gallery’s first room are two lengths of fabric, one a bright magenta and the other, a muted beige. Titled I Will Meet You Yet Again (2018), these cloths were exchanged by Mehra and the artist Shehnaz Ismail. The first, belonging to Mehra, originated in Sindh, and made its way to Delhi during Partition; the second belonged to Ismail, in Karachi. After exchanging the fabrics across the India-Pakistan border, each artist was given the task of applying rafoogari to the cloth in a symbolic elaboration of the care and nurturing that could attend to the fractured history—and contentious present relationship—between the two nations. Existing beyond the arbitrary borders imposed by violence and colonialism, these works give “Pale Sentinels” its affective power and its promise for an unbounded future.

“Pale Sentinels: Metaphors for Dialogues” is on view at Aicon Gallery, New York, until July 28, 2018.

To read more articles by ArtAsiaPacific, visit our Digital Library.