-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

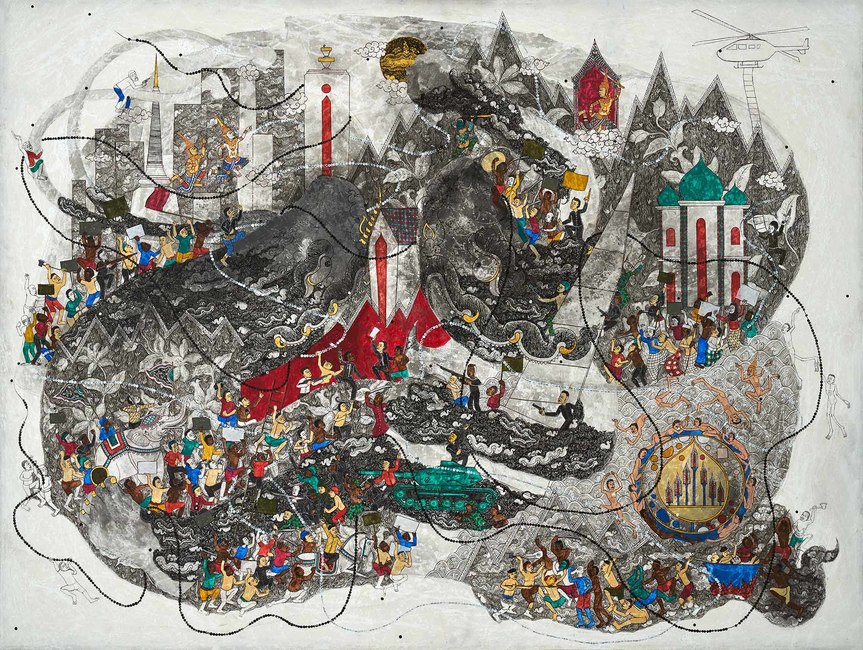

JEHABDULLOH JEHSORHOH, The Way of Life of Malay Locals in the Three Southernmost Provinces of Thailand, 2005, tempera painting on handmade Saa paper, 200 × 138 cm. All images courtesy the artists and Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur.

Co-organized by and held consecutively at two institutions located to the far north and south of Patani—Chiang Mai’s MAIIAM and Kuala Lumpur’s Ilham Gallery—“Patani Semasa” (“Patani Now”) looks at art in relation to a region covering the provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and parts of Songkhla—the site of the South Thailand insurgency, an ongoing campaign by Malay Muslim separatists. In its specificity, the exhibition both highlights an unfamiliar current of contemporary art in Thailand and asks, in bare terms: what is it like to make art in a place identified with conflict, at the border of two cultures, in a Muslim community within a Buddhist nation?

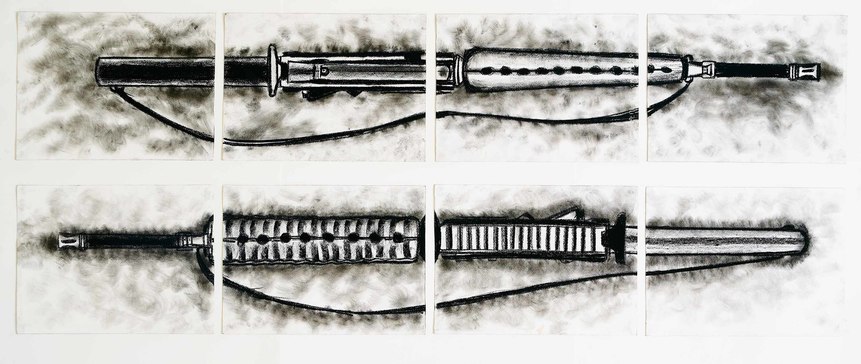

Most of the 27 artists participating in “Patani Semasa” come from the region, and in their works, there is little room for subtlety or addressing broad, abstract issues. Guns and weaponry are a recurring motif, as if turning them into art might somehow remove their threat—in Suhaidee Sata’s installation, Symbol of Violence 11 (2016), viewers walk through a corridor of rifles pointed at their heads, but the firearms are actually made of coconut husks, while Amru Thaisnit’s repetitive sketches of bullets and coffins in Symbols from Feelings (2017) are a way of finding peace of mind. The batu nisan (Muslim tombstones) and the faces of the dead pervading the show perhaps bear stronger testimony to the impact of violence on lives in Patani.

There are efforts to project an image of normal local life in the Malay Muslim community. Even as Korakot Sangnoy’s Movements on Turtle’s Back 1 (2015) uses the language of neo-traditionalist Thai painting to talk about the conflict between government forces and Islamist insurgents, Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh’s The Way of Life of Malay Locals in the Three Southernmost Provinces of Thailand (2005) and Sirichai Pummak’s Life of ‘Kedai Cina’ 2 (2016) in the same idiom depict peaceful village and market scenes.

Women are the heroes in Patani’s narrative—the ones left to remember the dead, keep the community going, and even to represent the beauty of Malay Muslim culture, and they feature strongly in the show. Ampanee Satoh’s photographs of women wearing hijab in everyday settings, titled Under the Hijab (2007) and Muslimah (2008), express a humor and warmth that counter assumptions about the role and lives of Muslim women in the region, as well as the mistrust often felt towards the traditional religious headgear.

I-na Phuyuthanon’s film, The Reflection of the Stigmatic Victims of the Insurgencies (2017), offers an intimate perspective of life in a small village in Yala where many men have been arrested, immersing the viewer in the making of batu beuloh, a dessert sold by the women left behind as a way to earn money. At its close, the artist performs the Sunat prayer at a site where incidents often occur, to ask for peace in this area.

The transnational nature of “Patani Semasa” formed a geography that was part of the joint exhibition’s argument, shaping its reception and interpretation. Pratchaya Phinthong, from Isaan, in north Thailand, traces a narrative of shared labor and commerce, solidarity and sympathy in his installation Namprik Zauguna (2017), centered on the story of an Isaan woman who moved to Patani with her Muslim husband and, after his death, started to produce a new brand of chili paste with other women in her adopted community, distributing it nationwide and abroad. Roslisham Ismail (Ise) from Kelantan, just south of the Thai-Malaysian border, builds on the collective memory and imagination surrounding the ancient Langkasuka kingdom shared by the folk of Kelantan and Patani in Langkasuka Cookbook (2012), an installation comprising the cookbook, a map of the artist’s favorite places to eat in his hometown, and a documentary video in which the artist interviews an elderly woman about her recipes. For this project, Ise traveled around the region collecting traditional recipes, detailing the personal and shared histories involved.

Literature provided on Patani and the insurgency gave a taste of the complexity of the region’s situation, and the exhibition itself revealed contradicting perspectives on its realities. Yet “Patani Semasa” brought us back to something basic—the importance of art-making for the individual and communities, and audiences beyond them, perhaps especially in sites of conflict and crisis. Art here is made to remember the dead, to expel demons, as a gesture towards peace, and to find an expression for and a way to connect others to a specific experience and culture.

“Patani Semasa” is on view at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, until July 15, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.