-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

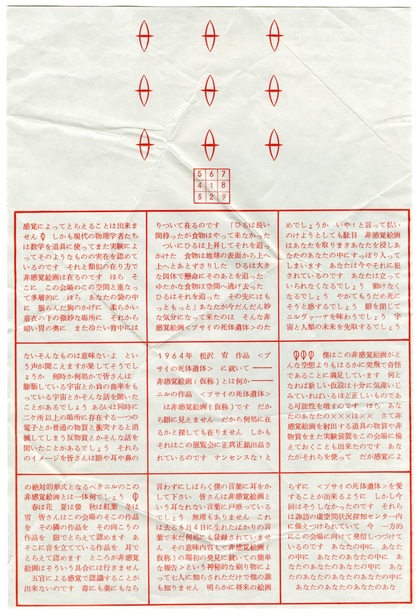

Installation view of “Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s,” at Japan Society Gallery, New York, 2019. Photo by Richard Goodbody. Courtesy Japan Society.

Based on scholar and curator Reiko Tomii’s comprehensive tome on the same subject, Japan Society Gallery’s exhibition “Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s” revisited a spirited moment in the contemporary art scene following World War II. Tomii’s in-depth expertise served as the primary guiding hand for the retrospective that looked back at Matsuzawa Yutaka, considered the father of Japanese Conceptualism, and two collectives, GUN (Group Ultra Niigata) and The Play. “Wilderness” at once references the natural world, where these artists performed and set many of their installations, as well as the historical connotation of being “outside of the seat of power,” as Tomii states in her book. In this decade of political remaking and postwar recovery, they innovated new forms of conceptual art that challenged societal norms.

For Matsuzawa, the destructiveness of war propelled him to

search for meaning beyond the physical realm. His foray into parapsychology, the study of the paranormal, led him to formulate his own psychological theory about non-sensory cognitive abilities, such as precognition and clairvoyance. The surrealist series “Psi Works” (circa 1960–63) consists of manipulated objects and collages, like a book with its pages cut out or a portrait of a pilot with his face missing, which he placed in a reception room of his house in Shimo Suwa. A slide projection revealed fisheye images of this Psi Zashiki Room (1969). An even more detailed elaboration on “psi power” can be seen in the 71 text-based works collected into the portfolio The Whole Works (1961–71).

Matsuzawa sought to rethink the institution of art altogether, coming up with the idea for “imaginary exhibitions.” A magazine ad for “Independent ’64 in the Wilderness” invited participants to “keep your entry in your hand and deliver the formless emission from it (imaginary work) to the exhibition site,” the implied delivery method being telepathy or some such supernatural power. Matsuzawa even selected a nearby location, Nanashima Yashima Highland, where the invisible showing was supposed to take place. His disdain for the material world only intensified. A replica of his Banner of Vanishing (Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate, Anti-Civilization Committee) (1966/2016) succinctly communicates his frustrations with contemporary civilization. He used the banner in a secretly staged performance on the sacred grounds of Mount Misa Shrine in his hometown.

Around this same time in the 1960s, two collectives formed. Recent graduates Tadashi Maeyama and Michio Horikawa led GUN, ironically named after their origins in a remote, backwater region of Japan. They burned through their financial resources quickly, but not before executing their best-known performance Event to Change the Image of Snow (1970). Driven by the desire to break up Niigata’s dreary, six-months-long winter, the group used a pesticide sprayer to blanket the white landscape in bright red, yellow and blue pigment. The beautiful display, which soon disappeared under the falling snow, was thankfully recorded in photographs. After the group disbanded, Maeyama went on to create several politically charged works. A reaction to the conflict in Vietnam, his Antiwar Flag (1970) depicts blood dripping from the red stripes of the American flag into the red circle of Japan’s “sun-mark flag.” Responding to another era-defining event, Horikawa began his series “Mail Art by Sending Stones” in 1969 following the Apollo 11 moon landing, and even mailed a stone to President Nixon.

Based in Osaka, The Play constitutes the second collective. Their quirky efforts included Voyage: Happening in an Egg (1968), launching a large, fiberglass egg into the Pacific with the hopes that the current would carry it to North America. In Current of Contemporary Art (1969), the group rowed from Kyoto to downtown Osaka on a Styrofoam raft shaped like an arrow. The exhibition offered a seating area outlined in the same shape, where viewers could watch footage documenting the performance. The Play continued to devise new works well into the next two decades, and spent ten years attempting to get lightning to strike a 20-meter-tall pyramid they constructed as part of their project Thunder (1977–86).

In the exhibition, the practices of these artists were situated alongside mentions of other notable artists and movements of the time, from Yayoi Kusama to Yves Klein’s immaterialism. “Radicalism in the Wilderness” celebrated a unique period not only in Japanese contemporary art but also within a global context.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s” is on view at the Japan Society Gallery, New York, until June 9, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.