-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “(Re)collect: The Making of Our Art Collection” at the National Gallery Singapore, 2018. All images courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

(Re)collect: the Making of Our Art Collection

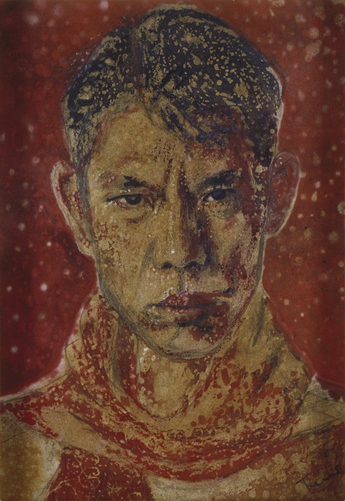

The first work to ever be accessioned into the collection of the National Gallery Singapore (NGS) was Chuah Thean Teng’s Self-Portrait (circa 1950s), depicting the Malaysian artist with a stern gaze hooded by furrowed brows. Positioned at the very beginning of “(Re)collect: The Making of Our Art Collection,” presented by the NGS and comprising over 100 works, the canvas set the tone for focused self-reflection, undertaken by NGS curator Lisa Horikawa to examine the origins of the museum’s collection of 19th- and 20th-century Southeast Asian art. Through its chronological layout, the show was able to speak to the major cultural shifts that have unfolded in the country and the region from the 1950s to the present, and their impacts on the collection. Also tied into this investigation, however, were broader questions as to the role of museums, curators and their relations to viewers.

Museums can often be perceived as opaque and slow-moving. Indeed, with most collecting institutions, the majority of holdings are kept under layers

of protective paper, plastic and wood in storage facilities. While curators are tasked with understanding these objects and their stories, and assessing blindspots where certain narrative threads could be developed, this is commonly done behind closed doors. What gave “(Re)collect” its edge, therefore, was its honest evaluation and laying bare of what is and isn’t represented by the NGS. One of the exhibition’s seven sections directly juxtaposed the collection’s strength—ink paintings, particularly works that

push the boundaries of the medium, such as Chen Wen Hsi’s abstract Black Mountain (circa 1970s to ‘80s)—with its weakness: photography, represented by Lee Lim’s black-and-white images of fog-shrouded palm trees and lakes,

the dominance of white spaces in which nevertheless recall the influence of traditional Chinese ink works. Similarly refreshing was how “(Re)collect” took on the NGS’s own knowledge gaps regarding the 8,000 pieces under its charge. Accompanying a clustered display of paintings donated by Singaporean philanthropist Dato Loke Wan Tho to the state in 1960, before the existence of NGS or any art-focused, state-run institution, was a sign prompting visitors to reach out should they know anything about the exhibits, some of which are missing titles, artist names, and creation years.

Spanning portraits, landscapes, still lifes and abstract works by artists from Singapore, Malaysia, China and Indonesia, Loke’s donation played a fundamental role in shaping the collecting practices of NGS, which, though heavily Singapore-focused, is regional in its purview. In addition to tracing the collection’s geneaology, the display of Loke’s gifted works highlighted the importance of philanthropy in the building of the collection, overturning the commonly-held presumption that the culture of philanthropy—especially when it comes to the arts—is foreign to or inactive in Asia.

In a section further into the exhibition, the weight placed by the NGS on connecting artistic practices through dialogues that reach beyond national boundaries was elaborated upon. Displayed

were paintings by Malaysia-born Latiff Mohidin, known for his wandering interest in tropes visible throughout Southeast Asia, from the arches of Penang shophouses as seen in Mindscape 17 (1983) to the curling banyan roots that penetrate Khmer temple walls (though this wasn’t evidenced in the show, which focused on works related to the artist’s home country). Also on view were sketches of scenes from the personal life of S. Sudjojono that showed an intimate side to the practice of an artist more often associated as an Indonesian nationalist painter, as well as the abstract painting Saeta 44 (1957), by artist Fernando Zóbel,

who was a patron of the arts in the Philippines himself.

Perhaps most clearly attempting to shed the mystery surrounding how collections are built was a room dedicated to the clues and tools that curators utilize in their research. Under a glass case was the reproduction of the back of Zóbel’s painting, showing stamps from the framers who handled the work, as well as the now non-existent Philippine Art Gallery, where it was once shown. These marks were cross-referenced with a catalog that describes the Gallery but makes no mention of the work, displayed above the reproduction. The materials were an example of the trails that have to be pursued by researchers, revealing the still-shifting grounds in the writing of art history and, above all, the importance of sparking questions rather than providing answers.

Chloe Chu is the associate editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“(Re)collect: The Making of Our Art Collection” is on view at the National Gallery Singapore until August 19, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.