-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

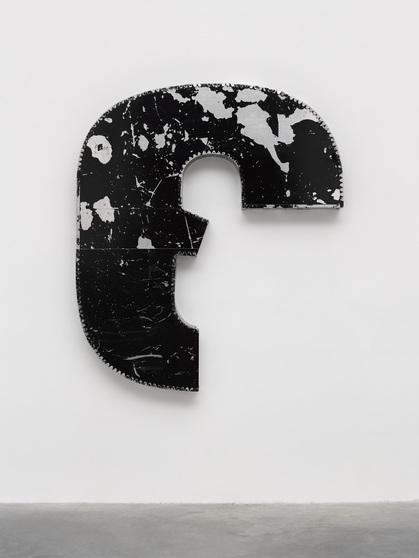

Installation view of VIRGINIA OVERTON’s “Alone in the Wilderness,” at White Cube, Hong Kong, 2020. All images copyright the artist; courtesy the artist and White Cube, London / Hong Kong.

During a night drive down the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike in the early 1950s, American architect and minimalist sculptor Tony Smith had an epiphany. Recalling the sublime qualities of the newly constructed environment of “stacks, towers, fumes and colored lights,” he commented in a later interview, “The road and much of the landscape was artificial, and yet it couldn’t be called a work of art . . . It seemed that there had been a reality there that had not had any expression in art.” Looking at Virginia Overton’s geometric wall-mounted and standing sculptures made from metal pieces of discarded corporate signage, shown at White Cube Hong Kong in the exhibition “Alone in the Wilderness,” one could see echoes of the boxy sculptures of Smith and other minimalists such as Donald Judd. Yet, now that we’re on the other side of the American Century, the timeworn materials of Overton’s sculptures look like symbols of the era’s demise while they tap into the growing contemporary nostalgia for the heyday of Made in America.

While preserving the battered patina of flaked-off paint and scratched surfaces, Overton’s manipulation and recombination of the aluminum pieces she discovered dumped in a field in rural Tennessee is minimal enough not to be obvious on first inspection. The black-painted Untitled (frequency) (2019), for instance, looks like a six-foot-tall letter ‘a’ with several corners precisely shorn off, while Overton appeared to have conjoined several right-angled pieces into a square with a pointed oval recess in the center for the composition Untitled (Tiger’s Eye) (2019). Some sculptures appear referential, such as Untitled (TN) (2019), an amaranth-colored aluminum parallelogram, which echoes the shape of Tennessee on a map, while the irregular, curving black metal bars of Untitled (clouds) (2020) are meant to evoke piles of white fluffy vapors. The addition of a bulging, pink neon light to Untitled (#11 Pink) (2020), a 2.5-meter-tall truck rail placed vertically from the floor up, gave the abstract work a surprisingly human quality. The most vivid protagonist in this forlorn object community was Untitled (V) (2020), a white V-shaped outline tipped over on one end and conjoined to a black wedge; several holes drilled through the surface allow a red glow to emanate from within in what must have been intended as a self-portrait.

Overton’s approach to these found materials is wide-ranging, often to a fault. The self-referentiality of Untitled (V) recalls Marcel Duchamp’s readymade sculptures while other works have more abstract-expressionist tendencies, echoing a pre-minimalist sculptor like David Smith, whose metal forms evoke the gestures of a hand. The latter impulse was particularly apparent in two free-standing sculptures: Untitled (flourish) (2020), of curving black-painted bars arranged in semi-arches like leaves, and Untitled (vintage geometry) (2020), whose mixture of straight and curving black forms is reminiscent of a surrealist drawing. Meanwhile, Overton’s two-dimensional collages of cut shapes, while rendered in the same black or deep pinkish-red of the sculptures, are complex forms resembling futuristic skyscrapers or Constructivist architectural plans, rather than postindustrial relics, and lack the economy of means and industrial grit of the sculptures.

Echoing the American mythology of rugged individualism, the show title perhaps refers to how the original abandoned metal pieces looked when the artist found them in the field, but neither a sense of aloneness nor the wilderness shone through within the minimal-luxe gallery. If there was an allegory being told by these weathered forms, it could be about rapid cycles of change, and waste, produced by 20th-century capitalism. That Overton saw potential to repurpose these massive found objects as art brings a certain era of material history to the fore but the artist’s contributions to—rather than mere continuations of—the legacies of American postwar sculpture feel slight.

HG Masters is deputy editor and deputy publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.

Virginia Overton’s “Alone in the Wilderness” is on view at White Cube Hong Kong until November 14, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.