-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

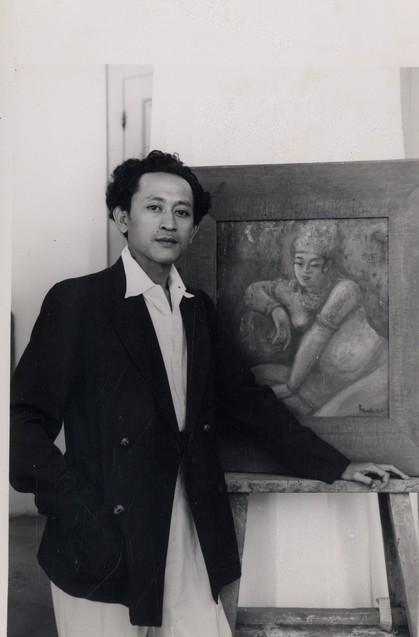

Installation view of THE DJAYA BROTHERS’ “Revolusi in the Stedelijk,” at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2018. Photo by Gert Jan van Rooij. All images courtesy Stedelijk Museum.

The premise of the most recent exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum—which featured paintings and watercolors by Indonesian painters Agus and Otto Djaya, made during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–49)—set viewers up for a highly politicized show, starting with the title, “Revolusi in the Stedelijk.” The works on view had been donated to and shown at the Dutch museum in 1947, but then vanished from public sight for the next 71 years. In 2018, these works were shown for the second time as part of the “Stedelijk Turns” program, a curatorial project showcasing the museum’s contemporary and modern collection.

“Revolusi in the Stedelijk” was presented with archival material on loan from the National Museum for World Cultures and Leiden University Library, and was significant as, historically, museums in the Netherlands have rarely showcased modern Indonesian artists. Brimming with this potential for education and postcolonial awareness, the show was marketed as an opportunity to understand hidden or untold stories of the Indonesian-Dutch relationships.

Agus Djaya and his younger brother, Otto, lived and worked in Java in the early 20th century. In 1947, at the height of the revolution, they were invited to Amsterdam to study at the renowned Rijksakademie by a government-supported program that sought to bridge the two increasingly divided nations via arts and culture. At the year’s end, the work of the Djaya Brothers was shown at the Stedelijk by curator Willem Sandberg as part of a series of cultural campaigns to promote Indonesian independence in the Netherlands. The artists remained in Europe until the end of the conflict.

The Djayas’ presence in the Netherlands—and their absence from Jakarta during those crucial years—demands closer reading and exploration. Unfortunately, however, the exhibition failed to address important contextual events that framed the brothers’ stay in the region, such as the establishment of the Stichtingn Culturele Samenwerking (Sticusa, Foundation for Cultural Cooperation), which was founded to bridge the gap between Dutch culture and the cultures of the (former) colonies. Instead, the show took a more literal approach to the paintings, presenting them as they were when they were first shown in 1947.

Installation view of AGUS DJAYA’s Flight (L’épopée) (left), 1944, oil on plywood, 150 × 120 cm, and Dewas (Nymphs) (right), 1947/1948, oil on canvas, 113.6 × 85.9 × 4.5 cm, at “Revolusi in the Stedelijk,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2018. Photo Gert Jan van Rooij.

As informed by the exhibition’s didactics and documentation of the show in 1947, the siblings had taken on the role of actualizing the revolutionary spirit of the time through art. The development of modern Indonesian culture was characterized by a desire to break with the preferred aesthetics of the Dutch Empire, as evident in Jembatan Lima (1940), an expressionistic and colorful landscape inspired by Hindu-Javanese myths that was painted by Agus Djaya. Unsurprisingly, the use of language as a vehicle for expressions of identity and liberation was significant in the resistance. For example, Agus Djaya had initially signed his work as “Agoes”—the “oe” sound typical in Dutch spelling and perpetuated by the colonial administration—but reverted to the Bahasa-Indonesian spelling of “Agus” around 1947, as shown in the catalogs on display.

Installation view of OTTO DJAYA’s Wayang Kulit Show (from left to right), 1949, watercolor on paper, 36.5 x 25.6 cm; Kali with Crocodile and Other Figures, 1949, watercolor on paper, 36.5 x 25.6 cm; and The Battle (Fight Against Monsters, 1950, oil on board, 148 × 49 cm, at “Revolusi in the Stedelijk,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2018. Photo Gert Jan van Rooij.

The brothers were also able to subtly comment on the socio-political situation and tension in the Netherlands through their paintings. (The show included posters testifying that Dutch Labor Party voters opposed the military intervention in Indonesia.) Their form of resistance was non-aggressive, such as their rehashing of ancient Indonesian myths to reflect on the instabilities around them. For example, in Otto Djaya’s painting titled The Battle (Fight Against Monsters) (1950), we see a dark mythological war scene, inspired by the shadow puppet theater genre and with references to prominent Indonesian figures of the revolution and to the defeated Dutch “monsters,” who are depicted lying on the ground. The work was painted shortly after the Dutch government finally accepted the sovereignty of Indonesia in late 1949 after years of violent turmoil, and was subsequently donated to the Stedelijk Museum. The two brothers finally returned to Jakarta and to a future no longer dictated by the Dutch.

The unintentional takeaway from the show is that Stedelijk Museum wanted to showcase its political correctness in 1947. Both the museum and its curator, Kerstin Winking, missed an important opportunity to reflect on the creation and the implications of such works, and also their contemporary relevance in a divided world. The motives behind repeating an exhibition, with the same works, seven decades later, remains unclear, revealing nothing new—except for civilization’s consistent inability to truly progress and address painful pasts.

“Revolusi in the Stedelijk” is on view at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, until September 2, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.