-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

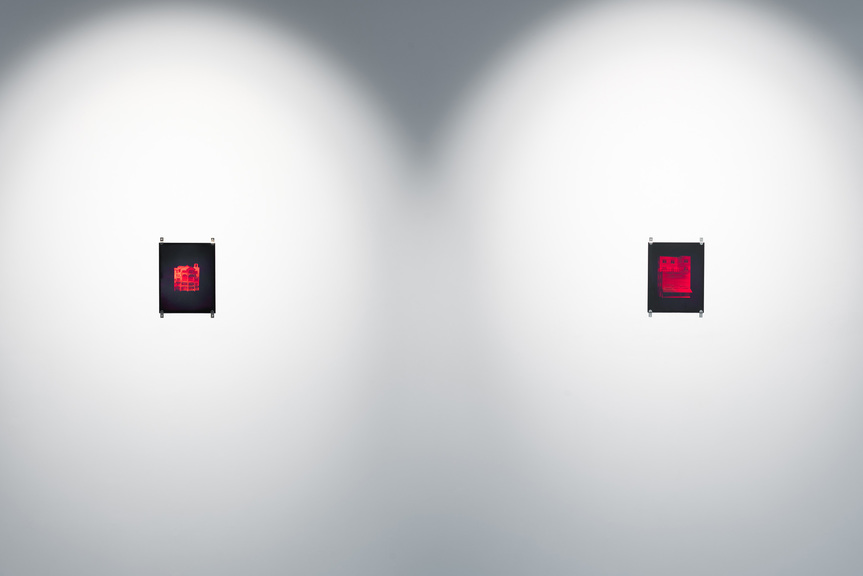

Installation view of TAO HUI’s (clockwise from left) Untitled (Holographic Building 01 and 02), both 2019, hologram, glass, 25 × 15 cm; and Screen as Display Body, 2019, LED screens, trolley, dimensions variable, at “Rhythm and Senses,” Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2019. All photos by Kwan Sheung Chi; courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai.

In the white-walled space of Hong Kong’s Edouard Malingue Gallery, four LED screens solely displaying red, blue, green, and white, respectively, were immediately visible from the entrance. Stacked on a shopping trolley, the four screens make up Screen as Display Body (all works 2019), a work highlighting the basic RGB color model with which electronic devices produce images, pixel by pixel. To its left, on the wall, hung Untitled (Holographic Building 01 and 02), two photographic depictions of architectural models. Created using laser holography, these two works demonstrate how multiple particles come together to render precise images from reality. This contrast between a whole and its constituents, between digital and real, set the tone for Tao Hui’s solo exhibition, “Rhythm and Senses.”

Born in Chongqing in 1987, Tao Hui trained in oil painting at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. However, he currently uses video and multimedia installations as his main channels of expression, which he attributes to his childhood in the countryside, where exposure to the outside world was limited and television was the main source of information and entertainment. Today, social media serves as the prevailing platform for these purposes, and in the exhibition, Tao evoked our reliance on digital communities by introducing two sets of blue, sliding PVC doors that demarcated the gallery space into three viewing sections, signifying the physical fragmentation of modern society as individuals seek communion online.

Situated in the central section was Pulsating Atom, a single-channel video installation displayed on a tall, vertically oriented screen. This recreates, in enlarged form, the experience of using the popular Chinese mobile app Tiktok, which allows people to watch and broadcast short movie clips—often performative and contrived—to the world. The work is narrated by a middle-aged gala singer, whose monologue on the atomization of society and obsessive social networking connects otherwise unrelated footage of various group activities, from dance and music concerts to smithing and sports. Sound and image are tightly edited to create a strict rhythm, indicative of the sense of order and routine that governs everyday life in professional and social settings alike. From a clip of chefs slicing ingredients with speedy, repetitive movements to a snippet of a cycling session at a gym, Tao reveals the ubiquitous, uncanny, mechanical rhythm of collective action within the “factory” of society, implying that just as professions and other social roles dictate our behavior, social media also teach us to express ourselves in ways that conform to their interfaces and to the tastes of their users. In this exercise, identities are mediated and diminished. On the desire to belong, the gala singer muses, “Perhaps human contact is the mightiest kindness in the world.” But like any social media feed, the non sequitur clips reflect only segments of strangers’ lives, preventing the viewer from establishing any real connection. The sense of isolation is heightened by the PVC doors shielding the space and the imposing quality of the tall screen, suggesting the inescapability of social networks and their attendant compromising of privacy and authenticity.

Installation view of TAO HUI’s White Building, 2019, video installation, sound, wood, LED screen, speaker, 124 × 286 × 130 cm, at “Rhythm and Senses,” Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2019.

Tao continues to explore the contrived nature of video narratives in the installation White Building, presented in the third partitioned space. Here, four screens embedded in a white, obsolete-looking control panel, recalling a broadcast or surveillance station in the 1980s, simultaneously play what appears to be a documentary showcasing the traditional Huanghe waist drum dance and the river’s majestic scenery. Swapping the audio tracks of the performance footage and nature shots to generate incongruity between sound and image, Tao makes obvious the act of editing, reflected here as a show of power as both ancient cultural traditions and natural landscapes are subjected to technological control.

As Tao presents screens in various forms—dissected into pixels, magnified as enablers of mass broadcast and viral sharing—the omnipresence of the device harkens back to the exhibition’s title, raising questions as to how we see, feel, and initiate contact in today’s world. “Rhythm and Senses” served as commentary on the redefinition of communities in the digital age, and the new—and isolating—paradigms of power and popularity that it has brought forth.

Tao Hui’s “Rhythm and Senses” is on view at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, until March 9, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.