-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of SAMSON YOUNG’s “Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me?,” at the Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, 2019. Photo by Michael Tropea. Courtesy the Smart Museum of Art.

In retrospect, the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair was a thermometer reading of the feverish times. Despite taking off amid the Great Depression and cross-Atlantic recession, the Fair was themed “Century of Progress,” and aimed to erect a vision of human perfection via technological prowess. Governments couldn’t afford to present pavilions, so, instead, American corporations showcased commodities, such as General Motors’ ultramodern vehicles that boasted manufactured colors brighter than the rainbow. For his debut solo exhibition in the United States, “Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me?” at Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art, Samson Young souped up the Fair’s 20th century engine of desire into a higher-octane bacchanalia of the present’s turbocharged utopian visions.

Abiding by the structure of the 1933 Fair, the exhibition, curated by Orianna Cacchione, was split into three portions related to the automobile, the mall, and the home. Each section was centered around an animated music video, part of what Young calls the Utopia Trilogy (2018–19). This trilogy was accompanied by a fourth video, The world falls apart into facts #2, featuring the Chinese University of Hong Kong chorus singing “The Dream-seller” by E. Markham Lee and AH Hyatt, the lyrics of which the exhibition title refers to. Young interprets the sweet yet eerie notion of “dreamselling” widely; each video congregates far-flung imagery from Miracle Whip campaigns, Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang) soldiers, the Da Da Company department store, Bing Crosby’s song “Have You Ever Seen a Dream Walking?,” and a commercial from the 1980s encouraging Hong Kongers to move to Singapore with the slogan “it’s a heaven over there.” The effect is like a deconstructed, exploding scrapbook—the world is unrolled, its remnants strewn about in all directions.

If utopia operates according to the logic of imminence, or a resolution-to-come, “Silver Moon or Golden Star” was situated in the aftermath; its creepiness felt as though a dream had curdled into a nightmare or cruelly dissolved upon waking. In the installation line follower (2018), a motorized lemon with protruding, frayed wires ambles along a magnetized track, impressing the haunted commodity sentience of Pixar’s animated Toy Story movie series. The room for the Da Da Company video, from the Utopia Trilogy, with its dropped ceiling, mismatched office chairs, and spare shop display fixtures, resembled an abandoned shopping center, a cadaverous relic of overzealous consumerist enterprises.

Also included in the show were ephemera from the 1933 Fair, such as a Century Dairy exhibition booklet, titled Dairy Products Build Superior People, with an illustration of an Aryan-looking family befitting of the art of the Third Reich. This artifact revealed the connections between discourses of technological progress and eugenics, as well as the embrace of technology by fascist futurism, a movement gaining momentum in the 1930s that has since resurged. This raises questions about the exhibition’s engagement of technology, as both a subject and the means of its articulation. Through masterful use of softwares like Blender and Rhino for animations, 3D printing for structures and picture frames, and CNC machines for milling sculptures such as the lion’s rear that towered over the show’s entrance, “Silver Moon or Golden Star” not only restated the World’s Fair in theme but as a cutting-edge technological exposition. In the show’s catalogue, art historian Seth Kim-Cohen connects Young’s own “overloaded aesthetics” to gesamtkunstwerk, the Wagnerian concept for a “total work of art.” Noting composer Richard Wagner’s posthumous associations with Adolf Hitler, who adored his music, and that “in the midst of our contemporary predicament, the gesamtkunstwerk might parallel capitalism’s total consumption of the Earth’s resources,” Kim-Cohen asks Young about these formalist choices: “Do these videos merely report the news that we’re fucked? Do they attempt to wake us from our imaginative coma? Are they a palliative, holding our hand through the end times?”

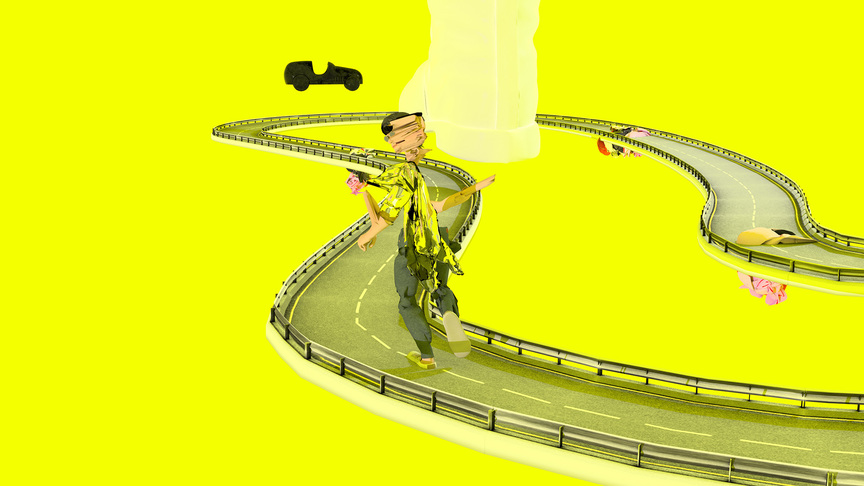

Young answers obliquely, chalking the bombarding style up to his messy mind, and insisting on open interpretation. “Art continues to be a place where the complexity of truth is not sanitized,” Young responds, “where truth stays messy, self-contradictory, uncomfortable, and complicated.” This sense of equivocation is inherent to the Utopia Trilogy series. The characters are both enhanced and imperiled by technology; the car in the video The Highway is Like a Lion’s Mouth (2018) both enables its driver to travail greater distances and endangers him, resulting in a crash that shatters him into glitching smithereens. Smooth renders of flesh are paired with jagged depictions of metal scraps, clangorous music with scenes of isolation, growing construction scaffolds with demolition.

This dialectical concern in Young’s work evokes what accelerationist theorist Jean-François Lyotard wrote in Libidinal Economy (1974): “Of course we suffer, we the capitalized, but this does not mean that we do not enjoy . . . we abhor therapeutics and its vaseline, we prefer to burst under the quantitative excesses.” Lyotard would later disown Libidinal Economy as his “evil book,” and accelerationism as a political program would become disparaged as its message gained popularity among neo-fascists and the alt-right. Yet accelerationism as a description of the brutally maximal sensorial experience of “capitalist realism” remains salient. Conceptually, this was the strength of “Silver Moon or Golden Star,” forcing a sense of discomfort with excess in viewers, in order to exacerbate an awareness of how we are all trapped in machinic loops of “creative destruction.” Yet, a question persists: in launching these confetti cannons of signifiers of utopian imaginaries, what does the work want the viewer to detect beyond the flashy extravaganza?

Leaving the show, I encountered a museum staff member whose job entailed monitoring the exhibition. She told me the blasting music is a bit relentless. “You really start to hear those songs in your dreams.”

Samson Young’s “Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me?” is on view at the Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, until December 15, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.