-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

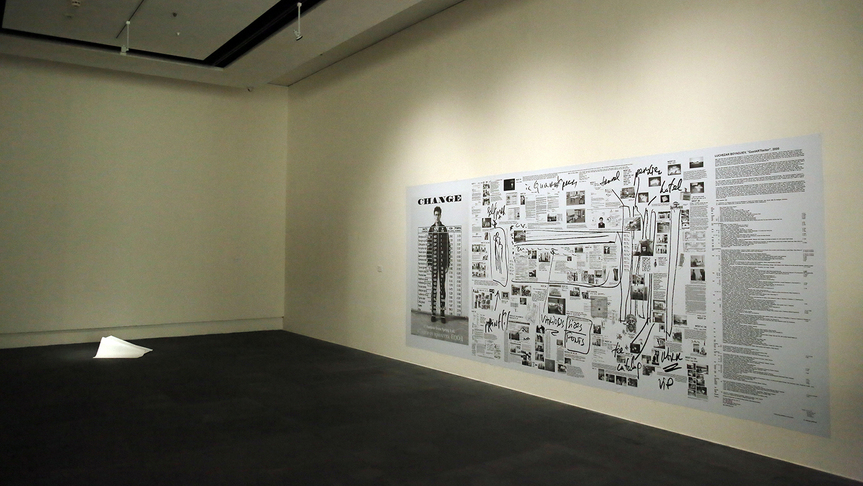

Installation view of “So Far So Right” at Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei, 2017–18. Courtesy Fang Yen-Hsiang.

The exhibition “So Far So Right: A Study of Reforms and Transitions,” curated by Fang Yen-Hsiang, was mounted with an open floor plan in a gallery within Taipei’s Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts. Visitors could read the text on Bulgarian artist Luchezar Boyadjiev’s GastARTbeiter (2000–07). The artwork takes its name from the German word gastarbeiter, which means “foreign worker,” and is a vinyl banner that tracks how capital moves across borders. At over five meters across and more than two meters tall, the artwork is packed with dizzying text and diagrams that records how money was moved between nations, institutions and corporations through commissions and sponsorship for the artist, who was acting as a temporary middleman after the Bulgarian Communist Party was toppled.

Another Bulgarian artist, Kosta Tonev, showed The Heavenly Bodies, Once Thrown into a Certain Definite Motion, Always Repeat (2013), whose title references Karl Marx’s general law of capitalist accumulation in his foundational treatise Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867). The work included pencil drawings of a manually driven Ottoman-era pleasure wheel prototype, a wheel-less concept car designed by Ford Motor Company in the 1950s, a 100-leva note that circulated for several years in Bulgaria after the fall of the Communist Party and subsequent inflation, and tulip bulbs that reached irrationally high prices after the species obtained a prized tint due to a viral infection. These were all objects that facilitated active capital circulation, as instruments of investment or temporary fiat currency.

Both of these works, along with Croatian artist David Maljković’s 2013 HD video Afterform, which animates cartoons published in a Yugoslavian architecture magazine, recall the dramatic changes in former communist countries in Eastern Europe when they were broken down into smaller nations. Just as Boyadjiev suggests, Maljković’s rhetorical irony indicates that, at the time, individuals were either bearers of the economic currents, or objective witnesses to tectonic, historic changes that were taking place.

One interesting aspect of the exhibition was how artists in Asia—specifically those from Taiwan and Vietnam—created a different landscape, even after taking into account yesteryear’s differences in political and economic systems between Taiwan and Vietnam or Eastern Europe. Several artists provided interpretations of others’ possessions, labor and identities; though they may not have personally experienced the dismantlement of communistic structures, they focus on individual lives that are difficult to observe within the massive systems that contain them, proffering private experiences that transcend boundaries.

Syu Jia-Jhen’s Public Tailor (2017) is a park bench that was made in China, shipped to Taiwan to inlay mother-of-pearl into its wooden surface, and then transported to Vietnam for assembly and used as public seating. The bench’s movement across borders and use of various industries channel the East and Southeast Asian regions’ interconnected commerce. In Berlin, Vietnamese artist Phuong Linh Nguyen embedded herself in a salon where Vietnamese immigrants provide manicure and makeup services, pouring herself into processes that require intimate physical contact as information and capital are exchanged. Taiwanese artist Wu Chi-Yu’s video installationReading List (2017) addresses the distortion of high-latitude countries on flattened world maps, while documenting the multifarious operations of book vendors in the northern Malay Peninsula.

Chen Szu-Han’s installation How to Stage an Archetype of Negotiation? (2017) positions an unidentified statue covered by an embroidered handkerchief, roses immersed in water and sealed in a glass box, wall drawings and a script written by the artist all over the exhibition space. It shrewdly unpacks a reflexive response to the conditions of refugees and the opacity in transnational mobility. The four artists that form Phụ Lục used the Thống Nhất (Reunification) train that connects Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City as their vessel to crisscross history, using second-hand and everyday objects as stage props to create a theatrical moment, and catalogued these items in a booklet titled TN1.

The exhibition touched on cold, rigid topics, including how power reshapes maps, borders, boundaries—such as the Nine-Dash Line, which charts China’s maritime influence in the South China Sea—and even international economics. The tone in the exhibition was one that could be found in the Taiwanese government’s New Southbound Policy, which is designed to strengthen trade ties with Southeast Asia and South Asia. With that in mind, artists in Taiwan are encouraged to look south as well, and listen to the callbacks as they establish their own cultural ties.

“So Far So Right” is on view at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei, until February 25, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.