-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

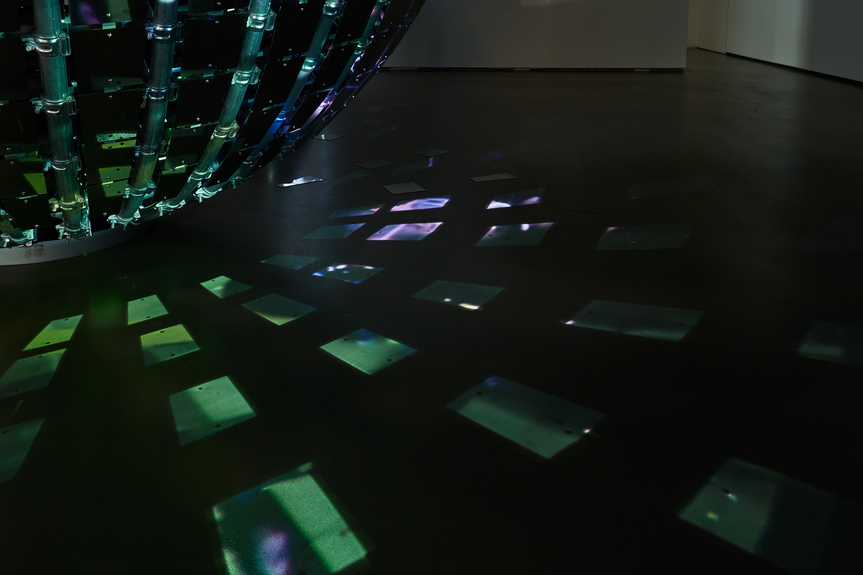

Installation view of JHEON SOOCHEON’s New Wolincheonganggigok, 2018, stainless steel supermirror comprising 1,000 individual pieces, 310 × 120 cm, at “Space of Contemplation,” Korean Cultural Center UK, London, 2018. All images courtesy the artist and the Korean Cultural Center UK.

In the course of his over 30-year career, Jheon Soocheon has created some genuinely notable artworks, not least among them The Line that Crosses America (2005), for which he wrapped a train in white fabric, and had it travel 5,500 kilometers across the United States to conjure the image of an artist’s brush painting a line. The concept of this piece is a relatively one-dimensional stab at the idea of an artist at work, extending the act of mark-making into a new form. Its strength is to be found, for the most part, in the novelty of its construction and poetic quality. The trouble, as illustrated in “Space of Contemplation” at the Korean Cultural Centre UK in London, is that while the artist is demonstrably capable of achieving aesthetic, conceptual and poetic heights, doing so together, or consistently, is no sure thing.

The central installation of the exhibition, New Wolincheonganggigok (2018), for instance, is an aesthetically and poetically adept offering.

A parabolic structure several meters across is covered with rectangular mirrors, each of which faces a different direction as a function

of the curve on which they are mounted. Meanwhile, a series of projectors cast footage from a nightclub and a busy subway station simultaneously onto the walls of the gallery and onto the array of mirrors, causing the images to fragment and be dispersed throughout the space. The title of the piece is taken from a 15th-century epic poem allegedly written by Sejong the Great, the title of which translates to Songs of the Moon Reflected in A Thousand Rivers. The original poem chronicles the life of Buddha. Jheon’s version, however, focuses on the empathic signification of the poem’s title. The macro images of people commuting and dancing in a club are suggestive of the isolation humans are capable of experiencing even when in each other’s immediate company, and this alienation is literally reflected when these images are projected onto and refracted by the mirrors of the main installation. The piece’s poetic qualities are evident, and with its sharp lines and capacity for making hard materials mediate affecting subject matter, it is aesthetically powerful and conceptually cohesive, if not especially far-reaching or complex. The next piece, however, falls short on all these counts.

Game & Play (2018) ostensibly “conceptualizes and expresses the human desire toward play,” according to the show’s accompanying text, through a one-meter cube constructed from approximately 35,000 dice made of transparent polycarbonate. How it achieves this, however, is anything but transparent. While a synecdoche by definition represents a concept—for instance a die symbolic of play—this isn’t to say it is also capable of conveying context or commentary, not unless that commentary is present somewhere in the synecdochical subject, and even then such an object can have multiple referents. Dice, for example, can also symbolise gambling, vice, luck, danger, and the relationship between symbol and referent can also be inflected by material and situation, or with irony, humor and a whole host of other figures. While conceptual sophistication isn’t a prerequisite for good art, without it, Game & Play is essentially a pile of plastic.

In “Space” (2017–18), a series of charcoal drawings on Korean paper, the artist appears to eschew concept altogether—at least beyond the uncontroversial idea that the line is the fundamental element of aesthetics. The resulting minimal and abstract images, such as a black square at the edge of a white plane with borders contested by charcoal marks, or a series of white-and-blue bars on black, nevertheless have an appealing aesthetic harmony to them.

Consolidating the inconsistency of this exhibition, a piece titled Time Gate (2018) has less aesthetic merit, and yet hints at a conceptual strength. In this creation, a wooden gateway bearing seemingly profound although not especially meaningful slogans—such as “Time builds up history colliding with desires” and “Cultural memory is recognition of time beyond past”—begins the exhibition, and is paired with a framed mixed-media image of a tree on a mottled blue background, positioned at its end. The sense of a single piece collapsing the space of an exhibition and the time taken to traverse it has potential to be compelling but, like much in “Space of Contemplation,” is ultimately perfunctory and unconvincing.

Ned Carter Miles is the London desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Jheon Soocheon’s “Space of Contemplation” is on view at the Korean Cultural Centre UK, London, until July 21, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.