-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of SIAH ARMAJANI’s Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room No. 3, 1988, mixed media, dimensions variable, at “Spaces for the Public. Spaces for Democracy.” NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore, 2019. All images courtesy NTU Centre for Contemporary Art.

These days, the names Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti may stir only vague associations with anarchy and injustice, but in the early 20th century, the two Italian immigrants to the United States, executed by electric chair after a highly politicized murder trial, were a global cause célèbre. In Iranian-American artist Siah Armajani’s exhibition “Spaces for the Public. Spaces for Democracy.” at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), visitors encountered a quasi-memorial to these men in the installation Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room No. 3 (1988).

Like most of Armajani’s works, Reading Room No. 3, part of his ongoing series of so-called reading rooms, is best appreciated by parsing its arcane historical, political, and philosophical references. Fortunately for the uninitiated, it includes a handy reference library of over 50 publications (some censorious of the judicial process, or outraged at the men’s fate), which range from cultural criticism to Persian poetry. These books are housed in a structure that comprises some half-dozen elements, with utilitarian constructions paraphrasing rustic American craftsmanship: severe seats (uncomfortably reminiscent of electric chairs), weathered-looking wood slats, and traditional tongue-and-groove floors.

Armajani’s reading rooms have always been formalized mandates, as opposed to cozy reading nooks; still, Reading Room No. 3 at CCA provides offhand visual delights, like gleaming copper-mesh awnings and vibrant teal-colored pvc panels. Another is the hundreds of erect yellow pencils planted throughout the installation, each helpfully stamped with the work’s title: two chairs sidle up to a table of bristling pencils, ready for a keen session of note-taking. Reading Room No. 3, with its opacities of commemoration, anarchism and democratic frailties, may be construed as the spatial embodiment of the artist’s conceptual muses—philosophers and writers who include Martin Heidegger, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and John Dewey. The latter held that reading is crucial to the democratic experience, thus imparting pragmatic context to Armajani’s interactive reading rooms.

Installation view of SIAH ARMAJANI’s (left) Street Corner No. 2, 1994, bronze, 171.5 × 279.4 × 22.9 cm; (right) Street Corner No. 1, 1994, bronze, wood, 134.6 × 280.7 × 33 cm, at “Spaces for the Public. Spaces for Democracy.” NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore, 2019.

The artist’s first institutional solo exhibition in Asia also included his early experimental films (all 1970). Computer-printed directly on 16 mm celluloid, these disclose Armajani’s early preoccupations with space, linearity, and the architectures of perception. One, an animation of arched bridge forms, is the direct antecedent of Street Corner No. 2 (1994), a graceful balance of two bronze arched bridges on view at the CCA. The bridge permeates Armajani’s six decade-long practice, as fed by Heidegger’s characterization of bridges as the “phenomenological gathering of object and idea.” Armajani’s witty and conceptual Bridge Over Tree (1970/2019) and the functional Irene Hixon Whitney footbridge (1988) both reflect these expressions of utility and connection: art intended for the public and—ultimately, through interaction and use—by the public; art which, as the artist describes, pursues the “nobility of usefulness.”

Always cerebral, Armajani has become increasingly introspective over the years. At the CCA were recent works from his Tomb series (1972–), including pensive ink illustrations on mylar which pay tribute to his influencers, including writer Frank O’Hara and philosopher Alfred Whitehead. Composed through layerings of reflective symbolism and obscured text, presumably excerpted from these authors’ works, the drawings are palimpsests of Armajani’s insights. Also from the Tomb series were two maquettes. Tomb for Heidegger (2012) is a bleak shed-like structure that articulates the philosopher’s notions of desolation, while the miniature Tomb for Arthur Rimbaud (2016) is an exquisite confection of balsa and aluminum, painted in baby blue and pink, alluding to the poet’s erotic reverie, “A Winter Dream.”

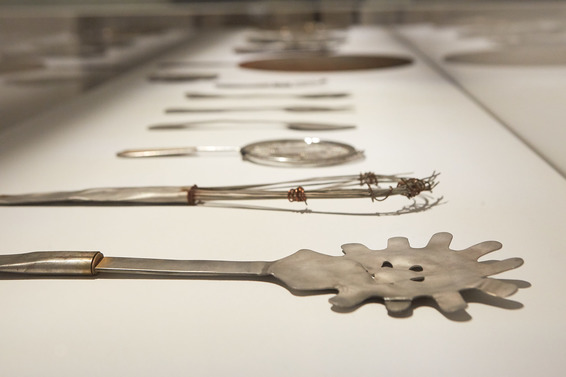

The works in “Spaces for the Public. Spaces for Democracy.” were strategic pedagogies: though his esoteric references may be demanding, Armajani’s use of populist mediums—maquettes, bridges, and reading rooms—invites curiosity and study. His conceptual exercises are distilled in Utensils (1975), a droll assemblage of old aluminum kitchen tools, flattened dramatically like pressed flowers in an album. No longer functional, the artist’s subtly beautiful deconstructions arouse wonder at their resemblance to pencil sketches, and at the same time, invite reflection on the intrinsic nature—or as the artist would have it, the nobility—of that which can be considered useful.

“Spaces for the Public. Spaces for Democracy.” is on view at NTU CCA Singapore, until November 3, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.