-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Speaking Power to (Post) Truth” at Jane Lombard Gallery, New York, 2019. All photos by Arturo Sanchez; courtesy Jane Lombard Gallery, New York.

An existential inquiry into the nature of knowledge and history beat at the heart of the group exhibition “Speaking Power to (Post) Truth” at Jane Lombard Gallery in New York City. In one room, curator Sara Raza brought together five diasporic artists from around the globe: Ergin Çavuşoǧlu, James Clar, Mounir Fatmi, Nadia Kaabi-Linke and Shahpour Pouyan. The close proximity of the varied practices—ranging from drawings on paper to LED lights and video—allowed the different works to connect and collide in surprising ways that the creators had not originally conceived but that nevertheless helped underline their meanings.

For the site-specific Mistake-Out Friedrichstadt (2018), Tunisian-born Kaabi-Linke traced the bullet holes of a wall that stood in the publishing district of Berlin, where she is based. The installation was previously mounted in Dubai. At Jane Lombard, the fragmented pieces, recreated from newspaper sheets painted over with white correction fluid, were spread across a blank wall, some even spilling onto the gallery’s concrete pillars. Kaabi-Linke’s work magnifies the threats to the freedom of the press. At the same time, the “whitewashing” of the news warns of not only censorship but also erasure.

Installation view of NADIA KAABI-LINKE’s Mistake-Out Friedrichstadt, 2018, correction fluid on serigraphy board, 430 × 640 cm, at “Speaking Power to (Post) Truth,” Jane Lombard Gallery, New York, 2019.

Installation view of SHAHPOUR POUYAN’s Memory Drawings, 2015–16, set of 39 drawings, mixed media on paper, 30.4 × 23 cm each, at “Speaking Power to (Post) Truth,” Jane Lombard Gallery, New York, 2019.

As with Kaabi-Linke’s wall installation, Iranian artist Pouyan’s Memory Drawings (2015–16) memorializes what has been lost through violent destruction. The 39 pieces are all of a single Muqarnas dome, a feature unique to Islamic architecture. The honeycomb-like structure sat atop Qubba Imam al-Dawr, an 11th century mausoleum completed in 1085 near Mosul, Iraq, that was destroyed by ISIS in 2014. Pouyan sketched the tomb from his memory, attempting to recover its presence in history.

A loss of cultural heritage can also occur through theft. In his experimental video The Human Factor (2018), Fatmi cut together scenes from L’inhumaine (The Inhuman Woman) (1924), a silent movie directed by Marcel L’Herbier, with images of the “exotic” Other. A split screen juxtaposes the geometric lines and patterns of the set with the fractal shapes and spires seen in distinctly non-Western buildings. A close-up of actress Georgette Leblanc wearing a feathered headpiece appears on screen next to a photograph of leopard- and zebra-skin rugs draped over furniture. The work draws a direct line between the “manifesto for Art Deco,” as the French film has been hailed retrospectively, and what the Moroccan artist describes as Avant-garde Primitivism. Historically, this “borrowing” of aesthetic coincides with France’s colonization of North Africa. Thus, Fatmi re-situates elements of architecture and design in postcolonial terms.

Other works rely less on cultural, historical frameworks and instead utilize the tools of design and technology to reflect our pervasive sense of cognitive dissonance. The site-responsive Silent Systems (2011–19) by Çavuşoǧlu, a Bulgarian-born and London-based artist, flattens a 3D rendering of a ship—a reference to Noah’s Ark, we are told—to an outline on the floor and wall. The result offers an optical illusion that visitors can step into. There’s also the added component of a CCTV camera pointed directly at the work, so anyone walking across can be seen on a monitor hanging in front of the reception desk. The relationship between migration and surveillance that the “silent system” alludes to certainly warrants further exploration, but perhaps it’s the inherent disconnect that comes across more strongly.

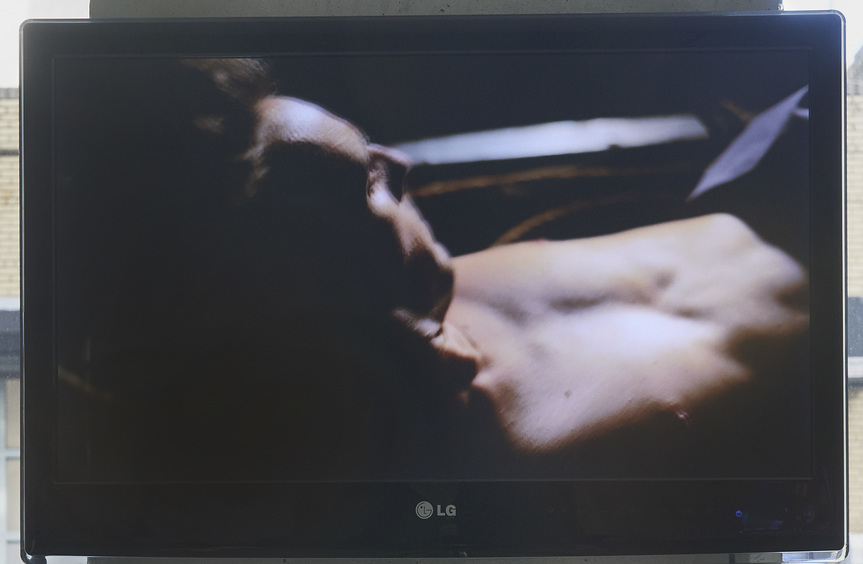

The nightmarish vision of a sleeping man ensnared by rope in Çavuşoǧlu’s video And I Awoke (2012) complements the aptly titled Wake Up (2012) by Filipino-American artist James Clar. An alarm clock trapped in a soundproof vacuum chamber that rings regularly but without anyone to hear stands in as almost too accurate a metaphor for the current socio-political state. Another work by Clar, New Dawn (2019), a colorful, James Turrell-inspired, LED sculpture, illuminates an abstract illustration of the sun dispelling the fog. But its fractured composition gives us pause from believing easy axioms in a post-truth world. As exemplified by these works, “Speaking Power to (Post) Truth,” Raza’s deliberate inversion of the phrase “speaking truth to power,” revealed itself to be both a break in logic and an urgent call to action.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Speaking Power to (Post) Truth” is on view at Jane Lombard Gallery, New York, until February 16, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.