-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

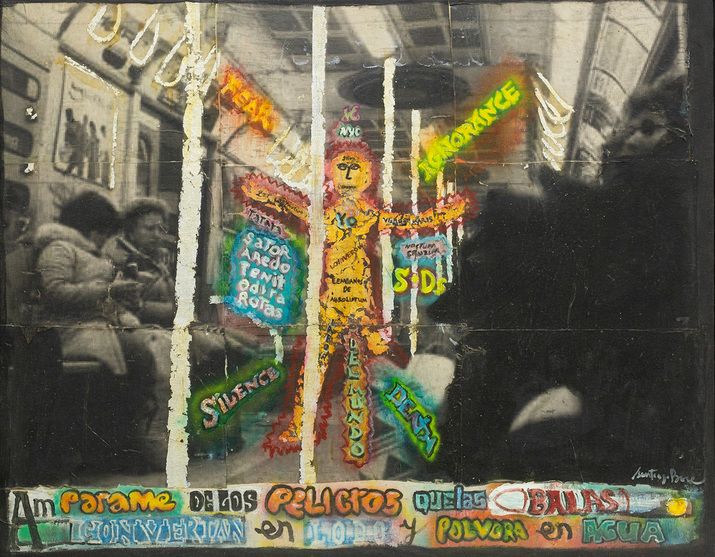

SANTIAGO BOSE, Carnivores of Session Road, 2002, acrylic and collage mounted on plywood, 91.8 × 134 cm. All images courtesy Silverlens, Manila.

Artist, theorist, and organizer Santiago “Santi” Bose (1949–2002) forged a singular practice that used indigenous media and site-specific objects to provoke a sense of native resistance to colonial and globalizing forces. “Striking Affinities,” the second in a trilogy of solo exhibitions curated by Patrick Flores at Silverlens, presented a cartography of Bose’s career through a selection of 30 mixed-media works and archival materials from the 1980s to 2002. Reflecting Bose’s life in Baguio and travels to Manila, Bali, New York, Adelaide, and the Spratly Islands, the works traced the span and periphery of political possibilities in the artist’s positionalities.

In the main gallery was a plywood vitrine of nine colorful pages and a wall-mounted cover from Balinese Diary (2000). The nine paper works from his stay in Indonesia utilize bank notes, matchbox stickers, educational posters, and photographic cut-outs. The diary cover, fashioned with a map, toy lizard, batik fabric, and a garuda figurine, pronounces in cut-out magazine lettering, “Asian Routes thru Red Eye Glasses,” hinting at the tinted perception of foreigners in exoticized lands. Behind the Bali installation were works about the artist’s hometown in Baguio, a similarly mountainous region colonized by the Americans at the turn of the 20th century. In the painted collage Carnivores of Session Road (2002), caricatures of Ifugao natives, wearing sport shoes and holding analog phones, carry a fried-chicken-wielding Colonel Sanders along the thoroughfare. In the background, Ronald McDonald is also seen. The work reverses the racist colonial concept of the “white man’s burden” quite literally, gesturing to the oppression of imperialist “carnivores.”

Following this selection were works created in or about New York, where Bose trained at the West 17th Print Workshop in the 1970s and ’80s. NYC Journals (2002) enlarges a black-and-white photograph of a subway train with pixelated passengers; in the center of the composition is a yellow, painted human figure surrounded by graffiti-style texts including “Fear,” “Ignorance,” and a Sator square (a Latin palindrome esoterically used as a talisman for protection). Below the scene, a prayer in Spanish asks that bullets be turned into water or dust, a reference not only to protection from the possible dangers faced in a foreign place, but also to bullet trains, connoting fear of the speed at which progress borderlines recklessness. Themes of self-protection and resistance likewise emerged in the Adelaide section, featuring a video slideshow of archival studies and catalogue entries detailing Bose’s proposal for the 1994 Adelaide Festival, an installation and performance titled Imagined Enclaves and Ephemeral Borders (1994), in which the artist traced his route to three locations in the city. Wearing a white jumpsuit decorated with talismanic symbols recalling the vests of Philippine soldiers during the late-18th century revolution against Spain, and carrying a backpack sprayer commonly used by Filipino farmers for their crops, Bose spraypainted a triangle onto the geography of Adelaide, gesturing to the shape of the trespico protective amulet, representing the three equal personalities of God.

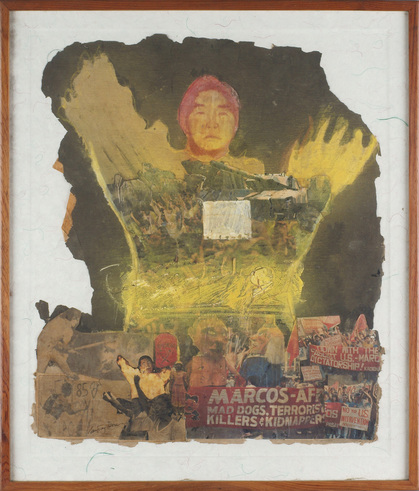

A small gallery bathed in warm yellow light was dedicated to projects on Manila and the Spratly Islands. EDSA MARCOS (1986) collaged scenes of mass protests along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in 1986 against the Marcos dictatorship and American meddling in Philippine politics. Also coined Yellow Revolution due to the yellow ribbons worn by protestors, the demonstrations ended with the departure of the Marcoses to the United States, and democratic reforms under president Corazon Aquino. Bose’s image depicts a central reclining Buddha—a symbol of renunciation and ascension to Nirvana—in bright yellow. On the adjacent wall, Dialogue with Chairman Mao (2001) depicts a caricature of the artist conversing with a bust of the communist leader on the notions of image and essence, gesturing at the semantics of identity and borders present within contested political geographies. The Bose caricature’s assertion, “This is not the Spratlys,” indicates the artist’s rejection of the British colonial designation of the territory, parts of which are claimed by China as well as Taiwan, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

“Striking Affinities” traced Bose’s engagement with themes of locality, resistance, and native preservation across his peripatetic career, locating his politics in an anxious, globalized world.

Santiago Bose’s “Striking Affinities” was on view at Silverlens, Manila, from March 20 to April 24, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.