-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Take ( ) at Face Value,” at Korean Cultural Centre Australia, Sydney, 2019. Photo by Documentary Photography. Courtesy the artists and Korean Cultural Centre Australia.

South Korean pali-pali culture derives from the expression meaning “quickly,” and denotes the country’s fast-paced mentality. Taking this concept of haste as a point of departure, “Take ( ) at Face Value” at the Korean Cultural Centre (KCC) Australia presented the works of ten artists based in South Korea who look past the country’s hypermodern veneer and challenge the Western capitalist ideals of progress that have taken root.

This localized context is provided by photographer Choonman Jo’s series Industry Korea (2014–19), depicting construction sites, and landscapes of cranes and towering skyscrapers that symbolize South Korea’s rapid industrialization. Jo’s documentary photographs are in tonal tension with the more absurdist and sardonic exhibits, such as Nayoungim & Maass’s intervention in the hanok (traditional Korean house) built into the KCC building. The duo hung eight scrolls from their Calligraphy (2019) series onto the hanok walls. These pieces ostensibly resemble traditional Korean calligraphic scrolls, but, upon closer inspection, are revealed to state flippant puns in English. Humorous phrases referencing Western pop culture such as “ANUS PRESLEY” crudely subvert the reverence with which symbols of tradition are typically imbued, signifying the loss of history and a distinct national identity in a rapidly modernizing and globalizing country. Also displayed in the hanok were four scholars’ rocks, from the duo’s Dream Stones (2019) series, on which examples of abbreviated “text speak”—including “STFU,” short for “shut the fuck up”—were scrawled in cursive, again compromising the solemn refinement of the traditional decorative objects through contemporary vandalism. These interventions suggest that a mindless drive towards progress and innovation may warp the past.

In contrast to Nayoungim & Maass, who provoke wider societal questions on tradition and national identity with their interventions, the pseudonymous artist Sasa(44) examines the implications of applying capitalist metrics to individuals. Sasa(44)’s display consists of several bound volumes in vitrines and chart-filled posters in Sasa(44) Annual Report (2006– ). The colorful line graphs and dense tables of statistics recall financial reports, but they actually record mundane details of the artist’s life, such as how many bowls of seoleongtang and jajangmyeon (noodles) he ate, how many movies he watched, and how many phone calls he made. Here, the corporate jargon typically used for economic measurements is ironically applied to the individual, questioning the obsessive quantifying and publicizing of success characteristic of our late-capitalist era.

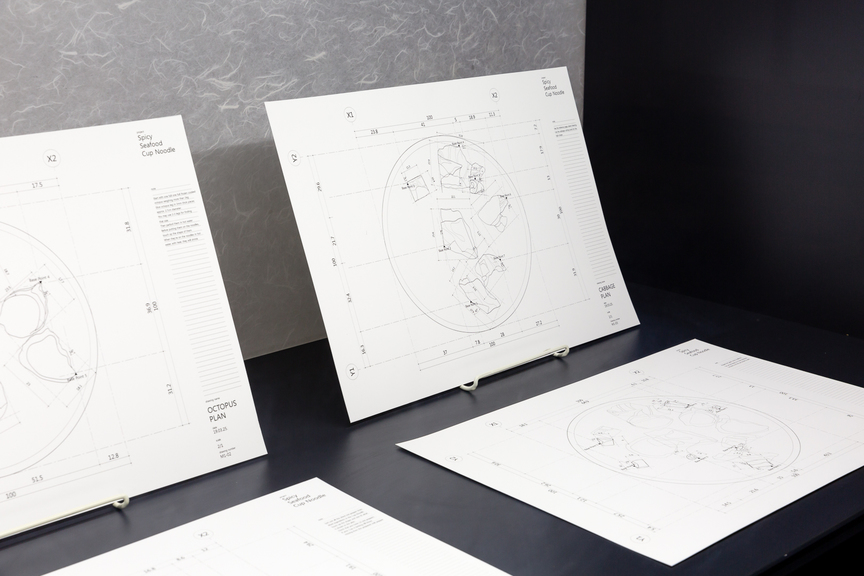

Detailed installation view of MINJA GU’s The Authentic Quality – Spicy Seafood Noodle, 2019, objects from documented performance, dimensions variable, at “Take ( ) at Face Value,” Korean Cultural Centre Australia, Sydney, 2019. Photo by Documentary Photography. Courtesy the artist and Korean Cultural Centre Australia.

Minja Gu takes a similarly tongue-in-cheek approach to the banal in her performance-installation The Authentic Quality – Spicy Seafood Noodle (2019). Tweezers, rubber gloves, scalpels, and other paraphernalia are meticulously displayed on clinical silver trays behind glass cabinets, while blueprints are pinned onto the walls, implying the planning of an elaborate heist, or a major surgical procedure. These expectations are undercut by an adjacent video showing the artist using the displayed tools to prepare a bowl of instant noodles that perfectly replicates the image on the packaging. In this documented performance, Gu painstakingly measures the ingredients, using stencils to cut out the exact shape of the green onions and octopus pieces, and delicately using medical equipment to arrange them. For Gu, two minutes is drawn out into hours, defying the demand for convenience and speed that instant noodles are created to satisfy, while revealing the ideal advertised on its packaging to be unrealistic.

In South Korea, the efficiency- and profit-driven logic of capitalism has “compressed” time, creating a milieu for pali-pali culture. The ten artists in this exhibition expose the flaws of this mentality, and highlight its social, cultural, and geographical consequences in their home country. It would be reductive to consider the show anti-capitalist, but it did request that viewers take time to reflect on the costs of uncritically embracing models of development—a potent reminder to never take promises of progress at face value.

“Take ( ) at Face Value” is on view at the Korean Cultural Centre Australia, Sydney, until September 29, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.