-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

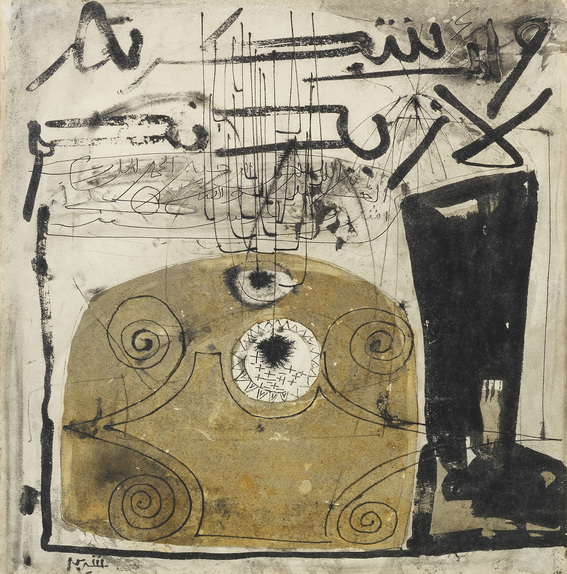

Installation view of “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” at Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 2020. All images courtesy Grey Art Gallery.

On the heels of the exhibition “Modernisms: Iranian, Turkish, and Indian Highlights from NYU’s Abby Weed Grey Collection,” which showcased works from the 1960s and ’70s, Grey Art Gallery’s first presentation of the year further widened the lens on 20th-century art from the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa. “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s,” curated by Suheyla Takesh and Lynn Gumpert, represented a joint effort with the Sharjah-based Barjeel Art Foundation to consider modernist movements from the region and the diaspora. The nearly 90 works by 55 artists reflect a period of decolonization and national identity-making that continues to bear resonance in the 21st century.

As if to emphasize the broad possibilities of Arab abstract art, the curators opted not to categorize the paintings, sculpture, drawings, and prints by country, nor to display them chronologically. Instead, the visually motivated configuration compelled viewers to draw their own conclusions about the aesthetic and thematic motifs that emerged.

Certainly, Western influences can be seen in some of the works, indicative of growing international awareness and the migration of artists. Algerian-born Abdallah Benanteur, who moved to Paris to pursue a career as a painter, pays homage to French Impressionism in To Monet, Giverny (1983). It wasn’t hard to discern how his brushstrokes of pinkish red and emerald green, surrounded by pale and dark blues, easily conjure Claude Monet’s famed garden. The painting hung alongside similarly colorful and abstract landscapes, including Benanteur’s The Garden of Saadi (1984) and Hind Nasser’s oil-on-wood Ayla (1975). The latter, thought to be titled after an ancient city in the artist’s native Jordan, evokes a lush, floral scene with her liberal application of soft pink, green, and yellow. The adjacency of these paintings suggested a greater art historical context beyond just the Eurocentric canon.

Abstraction through the use of Arabic letters served as one enduring method for expressing cultural authenticity. In Calligraphic Compositions (c. 1960s) by Sudanese artist Ahmad Shibrain, roughly painted script accompanies architectural, rectangular, and domed shapes. The style Shibrain contributed to creating, known as Sundanawiyya, incorporated Arabic calligraphy, Islamic motifs, and local imagery as a way to help define modern Sudan. Meanwhile, Egyptian artist Omar El-Nagdi’s repetition of the same Arabic symbol for the numeral one and first letter of the alphabet in Untitled (1970) reveals a meditative practice redolent of Sufi mysticism.

Other design elements stem directly from traditions such as Islamic geometry. Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair’s Interform (1960), the single sculpture of the exhibition, features straight lines and curves carved from wood. The cut-outs complemented nearby works that likewise play with space, such as Palestinian painter Samia Halaby’s White Cube in Brown Cube (1969), in which the contrast between different shades of brown provides the illusion of shadows and depth. Meanwhile, the late Kamal Boullata combined calligraphy and geometric patterns to produce highly graphical work. Unlike El-Nagi’s minimal compositions utilizing individual numerals or letters, Boullata’s brightly colored silkscreens reference entire phrases from Christian and Islamic texts, such as Fi-I Bid Kan-al-Kalima (In the Beginning was The Word) (1983), arranged into a symmetrical purple grid that almost looks digitally rendered.

Arab women artists in particular offered an alternative feminist gaze through their gestures to human figures. The late Huguette Caland—daughter of Bechara El-Khoury, the first president of independent Lebanon—abstracted the body to not only accentuate their eroticism but also recast femininity, sometimes with humor. The saturated orange-red contours of Bribes de Corps (1971) unmistakably reveal a woman’s backside. A Lebanese painter who continues to live and work in Beirut, Afaf Zurayk captures the sensuality of the abstracted body with a darker palette in her two Human Form oil paintings (both 1983). Another notable example included Celestial Forms (1973) by Simone Fattal, whose early work in pastel colors takes inspiration from both the human figure and nature.

The hope is that even more of these artists’ names will receive their long overdue recognition and be known to critics and scholars not just regionally, but globally. “Taking Shape” appeared to embrace the very large task of urging all of us to re-examine what perspectives constitute the default when approaching modern art.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” was scheduled to be on view at Grey Art Gallery, New York University, until April 4, 2020. Please check the exhibition web page for up-to-date information in light of Covid-19.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.