-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

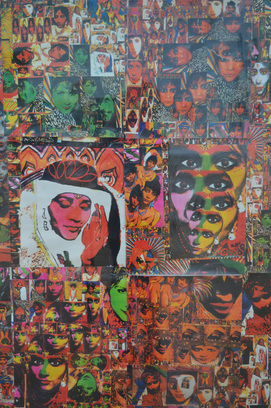

Installation view of CHILA KUMARI SINGH BURMAN’s “Tales of Valiant Queens” at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, 2018–19. Courtesy Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art.

Tales of Valiant Queens

Chila Kumari Singh Burman

The one room of Chila Kumari Singh Burman’s exhibition at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art was dominated by the spectacular My Valiant Queen Tuk Tuk (2017), a motor-rickshaw lavishly decorated with rhinestones and collaged imagery, from bejeweled eyes to paisley stickers, that reference Hindi comics and Pop Art in equal measure, introducing a portmanteau of the artist’s favored aesthetic. As the central work of this mid-career survey, featuring Burman’s works from the 1970s to present, the tuk tuk stands in for her father’s ice cream van—the Punjabi family’s business after they emigrated in the 1950s to the predominantly white, Catholic, working-class Liverpool. A photograph of the Burman Ice Cream van from the 1970s, with its incongruous, roof-mounted tiger figure attracting a crowd, can be seen among several prints hanging beside the tuk tuk. There is a celebratory nostalgia about this snapshot, Dad on Ship Coming to Britain, Three Queens, and Our Ice Cream Van (1995), though overlaid with the portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, the work becomes about dislocation, sovereignty and subjugation.

There were stark reminders of how the race, gender and class barriers the Burman family encountered formed the political dynamism of her work. In the lithographic print Shots – Peace and Love, Brothers, Sisters, and Little Children (1982), a man sits amid a post-industrial wasteland, flanked by a young Afro-Caribbean mother anxiously clutching her child and a girl smoking defiantly at the camera. The imagery evokes a variety of associations from social documentary photographs by Dorothea Lange and Tish Murtha to the films of Mai Zetterling. Thirty-seven years later, the scenes of austerity, alienated youth and the destruction of working-class communities in Shots remain a pertinent portrait of contemporary Britain. Similarly powerful is Burman’s Convenience Not Love (1986–87), which now appears prescient of Brexit; the mixed-media-on-paper work features the old, British, navy blue passport, the restoration of which became a totem for the Leave campaign. The adjacent caricature of Margaret Thatcher as the jingoistic John Bull, spouting anti-migrant, populist sentiments via speech balloon, connects Burman to the English satirical tradition of Hogarth while revealing the symmetry between the divisive racist politics of the 1980s and the current political crisis in the United Kingdom. Burman’s approach to political art reflects her understanding of how contemporary British visual culture remains invested in the legacy of Empire, and shows how regressive definitions of identity have gone unchallenged in post-colonial Britain.

The display included video interviews with Burman, and her personal archive of photographs, Indian comic books and exhibition ephemera that establish the importance of fusing her South Asian heritage with her current working environment in her practice. In defiance of marginalization in the predominantly white British art establishment, as in society at large, Burman’s self portraits present humorous narratives of minority empowerment that anticipate the work of Jasleen Kaur and Hetain Patel. The inkjet print Body Weapons (1992, remade circa 2012) portrays Burman as a punk rocker wearing a two-tone dress, while Shotokan – All You Need Is Love (1993, remade 2016) is a sequence of images depicting the artist as an “Asian Warrior Queen” striking martial arts poses in front of a community mural project that the artist was working on at the time. The large Autoportrait – Fly Girl Reaching Heights (1993) provides a dynamic compendium of self-portraits, prolifically repeated and manipulated by the artist, a manifesto for the artist’s struggle to bring her own identity into the public sphere of the gallery space.

One of the earliest pieces on view, Self Portrait in Sugar (1979)—made while Burman was still a student at London’s Slade School of Fine Art—encapsulates the artist’s enduring fascination with raw feminine power. Created by pressing her own body onto the print plate, it is still unsettlingly immediate and intimate. This vibrant celebration of the body is borne through to the most recent collages in the show, grouped together under the heading “Bindi Girls,” which explore contemporary female Hindu identity through subverting archetypes of the South Asian divine feminine. For instance, the subject of Parvati – Hindu Goddess (2017) more closely resembles a psychedelic rock star than a deity. A poignant work is Pestle (2006), of a young woman licking an ice lolly while eyeing a 99 Flake—treats that Burman used to sell as a teenager from her father’s van.

Chila Kumari Singh Burman’s “Tales of Valiant Queens” is on view at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art until February 3, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.