-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of "Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative” at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, 2018. Photo by Giorgio Perottino. Courtesy Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo.

For the exhibition “Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative” at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, co-curators Amy Cheng and Hsieh Feng-Rong invited artists to detail various cultures and historical accounts from across the Asian continent through personal storytelling. The exhibition—a result of the ongoing collaboration between the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo and the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai—unfolded through 12 “stories” in a variety of media.

Installation view of HAEJUN JO and KYEONG SOO LEE’s A Ship Believing the Sea is the Land, 2014, drawing, video wooden sculpture, wax, dimensions variable, at “Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative,” Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, 2018. Courtesy the artists, SBS Culture Foundation, and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul/Gwacheon.

On entering the show, visitors encountered a full-scale rowboat coated entirely in white wax. This dream-like vision was part of the multipart installation A Ship Believing the Sea is the Land (2014) by Korean duo Haejun Jo and Kyeong Soo Lee. Placed within the boat were sculpted wooden busts of Jo’s family members, including his pets, as well as a video screened on a television, which reconstructed an event in the 1970s when Jo and his father found a boat stranded in the countryside near Gunsan City, home to the United States Air Force’s Kunsan Air Base—a remnant of the Korean War. The work also included several framed pencil drawings hung on the surrounding walls—a visual and textual diary, the caption explained, of Jo’s father’s memories of family life. The interlacing of personal memory and collective history sank in this instance under an excess of visual information with little apparent connection, resulting in a confusing narrative.

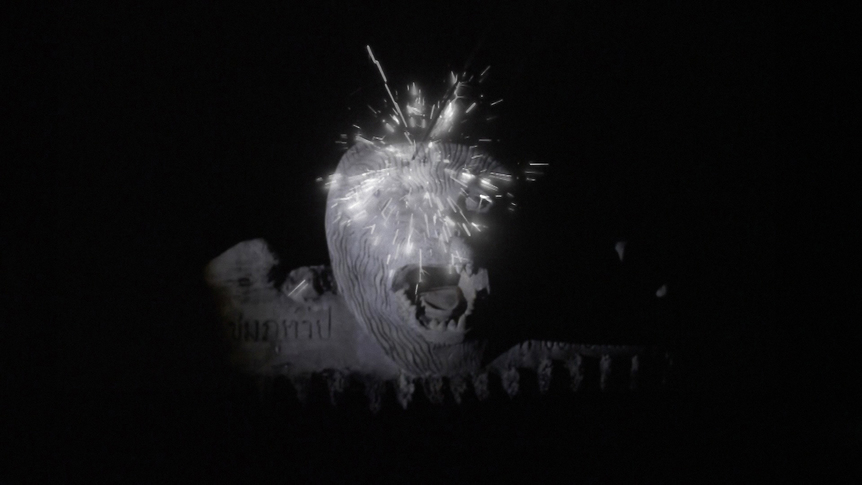

Contrastively, sociopolitical commentary was expressed concisely and poetically in Fireworks (Archive) (2014), a short film by Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, shot in the Sala Keoku sculpture park in Northeast Thailand, which is renowned for its Buddhist- and Hindu-inspired menagerie of concrete animals and gods. In the 1960s and ’70s, the rebellion of communist-sympathizing farmers in this region was crushed with extreme violence by the Thai junta, and Sala Keoku was partially destroyed for being a suspected stronghold of the communist rebels. In the video, sparklers, accompanied by menacing, crackling sounds, intermittently illuminate a pitch-black night. Shots of two concrete skeletons embracing on a bench, as if posing for a picture were intercut with those of an elderly couple, the woman limping on crutches, slowly wandering through the mysterious, sinister scenery. In this way, the film wove together visual clues that conveyed the region’s lingering memories of violence and war.

There were more direct references to history in the show, including Japanese photographer Tomoko Yoneda’s eight chromogenic prints featuring views of Sakhalin Island—the site of hostile jostlings between Russia and Japan throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. After the Second World War the island was annexed to Russia, and Japanese presence on the island was erased as civilians were deported and cities and sites were renamed. This obliteration was reflected in Yoneda’s skillfully crafted, disquieting and melancholic landscapes, such as Duè Village: Site of the First Prison Camp on Sakhalin (2012), which depicts abandoned shacks set against the scenery of the lush autumnal countryside. Similarly, in Oji Paper’s Former Maok Mill: Kholmsk (2012) a factory’s empty carcass evidences the devastation left behind by Soviet-Japanese conflicts.

The importance of imagination in shaping places and communities underlies Hong Kong Is Land (2014) by artist-architect duo MAP Office. The project proposes the addition of eight new artificial islands to the over 260 that Hong Kong already comprises. Eight detailed, beautifully drawn maps,including explanations of the respective islands’ functions, illustrate fantastical geographies. Among them, Island of the Sea suggests the possibility of a new alimentary economy through a system of aquiculture while Island of Endemic Species is a laboratory-jungle for experimenting with new varieties of living organisms. In the generally somber mood of the exhibition, this installation evoked the possibility of looking toward the future positively, prompting viewers to rethink Hong Kong as a sustainable metropolis.

“Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative” was a slow-paced, thoughtful exhibition, rewarding those who were willing to pay attention to research-based, layered projects. With a small but well-selected sample of the various approaches to storytelling from the broad field of contemporary Asian art, the show suggested that though art by itself cannot change future realities, it can at least offer fresh, alternative understandings of narratives of the past.

“Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative” is on view at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, until October 7, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.