-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

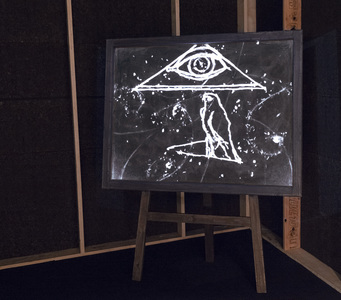

Installation view of WILLIAM KENTRIDGE’s “That Which We Do Not Remember” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2018–19. All images by Christopher Snee; courtesy Art Gallery of New South Wales. All images copyright William Kentridge.

As I looked through William Kentridge’s “That Which We Do Not Remember”at Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales, led by the multimedia artist himself, it became increasingly apparent to me that Kentridge, often described as a distinctive and powerful voice in the global contemporary art realm, is both erudite and generous with his ideas. The exhibition was curated by Kentridge and designed by Belgium-based set designer Sabine Theunissen, who has worked with the artist since 2005 on his stage-based projects. Drawn from the past 22 years, the animations, prints, collages, drawings, sculptures, installations and plans for opera sets, as well as Kentridge’s somewhat off-the-cuff exposition of his art, provided dazzling insights into his process. The artist also elucidated the historical context of his works—namely, apartheid, colonization and totalitarianism as both international phenomena and the specific conditions of South Africa, where he was born in 1955.

Kentridge’s works are often triggered by the detritus found in his studio, such as paper scraps, books and archaic costume cut-outs. He believes in the power of chance and prefers the frisson of the unknown. As a result, he avoids storyboards and preliminary sketches. The studio is a safe place for stupidity, he quipped. The importance of Kentridge’s work area to his process was alluded to in the show with a one-to-one scale recreation of the space. Nearby in the same dimly lit gallery was the bricolage Drawing for ‘7 Fragments for George Méliès,’ ‘Day for Night’ and ‘Journey to the Moon’ (2003), a life-size drawing of one of the studio walls with newspaper pages and drawings affixed. The drawing features in an accompanying nine-channel video of the same name. As the footage progresses, we see the artist at work in his studio, creating an animation with his signature technique of repeatedly erasing and drawing over the same piece of paper. A self-referential gesture to the process behind his moving images, the mesmerizing seven-minute flipbook animation Second-hand Reading (2013) comprises sketches of the artist as he paces endlessly across the rapidly turning pages of a book.

Elsewhere, several open-fronted viewing pods with Portuguese-cork-lined exteriors allowed music to spill from moving images and coalesce throughout the space. Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791) accompanies Learning the Flute (2003), a chalk board animation where white lines and dots endlessly form and dissolve while Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2 (1944) mixed harmoniously with the Ethiopian and Eritrean music coming from What Will Come (Has Already Come) (2007), a drawing reflected in a rotating cylindrical mirror that distorts straight lines into intriguing anamorphic conundrums.

The key work in the exhibition was a chilling eight-channel video I am not me, the horse is not mine (2008), which was commissioned for the 2008 Biennale of Sydney and gifted to the Gallery in 2017 by local collectors. Exploring his passion for early 1920s movies, Kentridge uses archival cinema clips. These scenes appear alongside quotes from politician and one-time-Joseph-Stalin-favourite Nikolai Bukharin’s 1937 show-trial where he pleaded for his life. Prancing across the other screens are giant noses inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 absurdist short story The Nose, which was satirized by Dmitri Shostakovich in his 1928 opera lampooning corruption and the suffocating confines of government hierarchies. I am not me, the horse is not mine comments similarly on the violence and absurdity of our times.

But not everything in Kentridge’s world is absurd. Parcours d’atelier (2007) is a delightful scribble representing the artist’s path around his studio as he waited for his muse to appear and as he summoned up energy to begin drawing. His procrastinations are ordinary: answer an email, take the dog out, change the music. “That Which We Do Not Remember” was evidence that Kentridge is a humble yet masterful artist whose outlook on the world is determined, above all, by the spirit of humanism.

Michael Young is a contributing editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

William Kentridge’s “That Which We Do Not Remember” is on view at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until March 24, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.