-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view at JUN YANG’s “The Artist, the Work and the Exhibition” at Kunsthaus Graz, 2019. Photo by Universalmuseum Joanneum / N. Lackner. All images courtesy the artist and Kunsthaus Graz.

Just who is Jun Yang? As his solo show, “The Artist, the Work and the Exhibition,” at Kunsthaus Graz suggested, the answer depends on your perspective—and a great deal else. Co-organized by the artist himself along with curator and Kunsthaus Graz director Barbara Steiner, the retrospective spans two floors and features works in an array of media, including paintings, videos, photography, and posters, among other things, produced by Yang over the past two decades.

Although the exhibition’s ostensible starting point is the Chinese-Austrian artist’s wide-ranging body of work, one of the curatorial aims, as the catalogue indicates, is to deconstruct or “pluralise” singular notions of artistic selfhood. A solo exhibition that is simultaneously a group exhibition, it includes works by a number of other artists, from Yang’s long-time and recent collaborators to South Korean-born, San Francisco-based Jun Yang, whose shared name but divergent artistic practice problematizes notions of artistic individuality. The result is variously provocative, insightful and humorous, if, at times, disorienting—an experience reflective of the complexities of contemporary identities, with their shifting and often contradictory geographical, national and temporal points of reference.

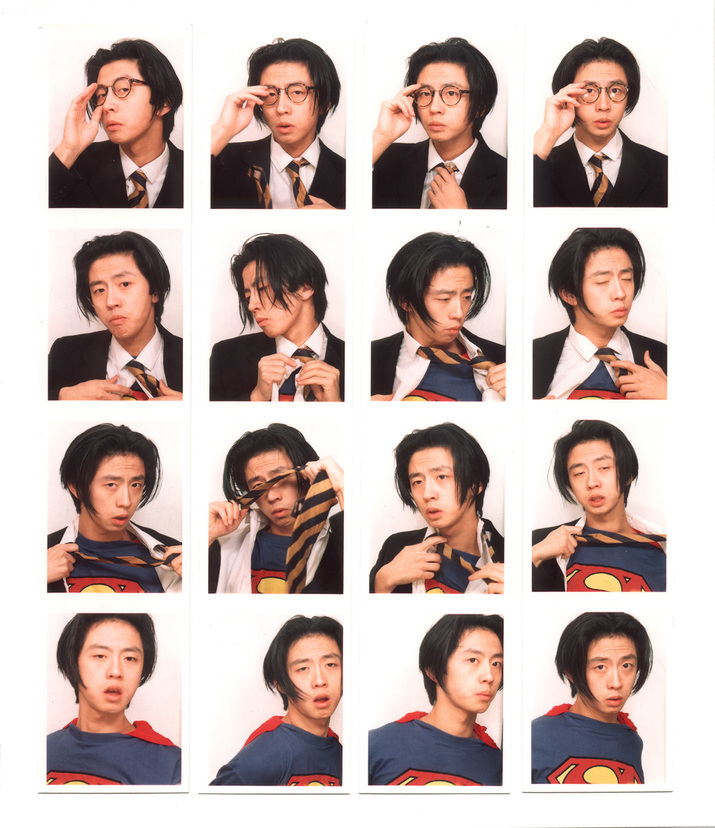

In From Salariiman to Superman (1997), for instance, Yang photographs himself undressing in a train station photo booth after work to reveal a Superman costume under his suit. At the time, Yang had a day job at the United Nations in Vienna; his metamorphosis from businessman to Superman in this work questions the ritualistic conformity of collective identity and reveals the performative process that constitutes subjectivity. Ten years later, artistic biography is playfully taunted and deconstructed, as in Untitled (Mail for…) (2006), which comprises incorrectly addressed letters sent to Yang (Tun Yang, Jan Jung, Jün Yan, and even Miss June Young), or Jun Yang Looking for Jun Yang (2006), which began as a series of posters by various graphic designers calling for others by that name to contact the artist, but has since expanded to include photographs of the artist and his namesakes.

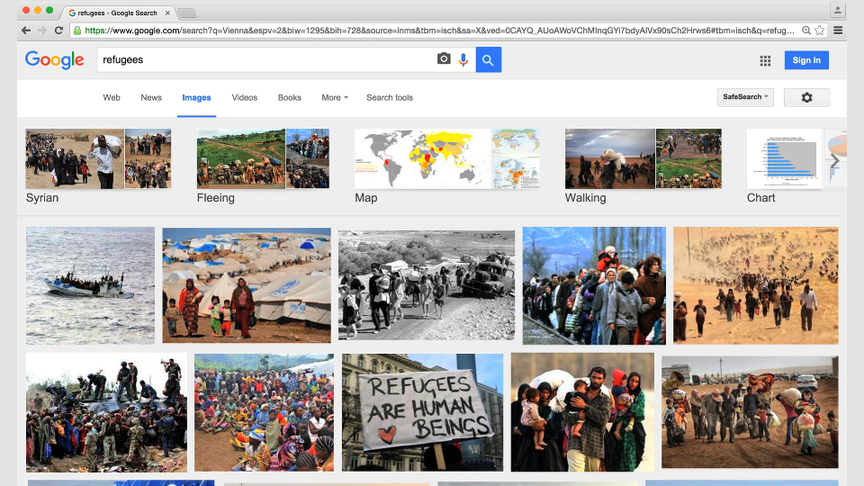

Conversely, his recent work disengages (although not entirely) from autobiographical-based performativity in favor of overtly political themes. In his video Becoming European or How I Grew Up with Wiener Schnitzel (2015), Yang extends the notion of found footage to include Google searches. Words and phrases such as “migration,” “refugee crisis,” and “Chinese” yield different results depending on the language he uses, underscoring the perspectival nature of “European” identity and the manner in which technology influences this ongoing process of negotiation between peoples and cultures. In The Past Is a Foreign Country – A Landscape in 4 Scenes (2018), Yang and Japanese performance artist Michikazu Matsune engage with territorial notions of borders on the divided Korean peninsula by staging history in four interconnected instalments.

As Yang suggests in countless works over two decades, an individual without a past is an individual without a future, and the same can be said of the many cities and countries that anchor his art. In his Alain Resnais-inspired short film The Age of Guilt and Forgiveness (2016), two lovers discuss Japan’s 20th-century history and consider questions individual and collective guilt. When one character remarks, “We have a responsibility to inherit the past,” the viewer cannot help but think of Yang’s home country, Austria, and its ongoing efforts in dealing with the burden of its post-war history. Similarly, in his 2010 short film Seoul Fiction, an elderly couple travels by bus to the city to visit their children, but are struck by the uniformity of the country’s rapid modernization—a situation that finds obvious parallels in Japan and China. “When everything looks the same,” the grandmother wonders, “how are you supposed to find your way home?”

A certain artistic trajectory, then, begins to emerge in which Yang’s personal presence in many of his early works gradually cedes to an interest in biography as an aesthetic starting point and, eventually, a preference for the political and social over the personal. Whether this leads us any closer to answering the question about the artist, the work, and the exhibition is perhaps beside the point. Rather, as this substantial exhibition at Kunsthaus Graz demonstrates, his oeuvre suggests a boundless curiosity shaped and informed by that most elemental of relationships, the individual within society.

Jun Yang’s “The Artist, the Work and the Exhibition” is on view at Kunsthaus Graz until May 19, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.