-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of RAMIN HAERIZADEH, ROKNI HAERIZADEH and HESAM RAHMANIAN’s mixed-media installation Another Happy Day (2016–17) in “The Creative Act: Performance, Process, Presence” at Manarat Al-Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi, 2017. Commissioned by the Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority. Courtesy Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai.

Anticipation surrounding the launch of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is heightened as development on Saadiyat Island, home to Abu Dhabi’s megamuseum district, continues to progress. The institution may not have a building yet, but it does have a growing collection, and its second exhibition “The Creative Act: Performance, Process, Presence” suggests the breadth and depth of what will come when the museum does eventually open its doors. Featured at the Manarat al-Saadiyat exhibition space, the off-site show brought together works from the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi’s permanent collection with new site-specific commissions that highlight connections across time and geography through performance.

The artworks that made up the first chapter lay the groundwork for performance as an increasingly relevant medium in conceptual art, focusing on painting, sculpture and installations that utilize everyday objects. Special focus was given to the Gutai Art Association, a Japanese avant-garde collective that was active from 1954 to 1972, featuring paintings created as a performative act by Shiraga Kazuo, Motonaga Sadamasa and Tanaka Atsuko. Alongside these works, conceptual artworks by members of various art movements, such as Kinetic art, Minimalism, and Fluxus also explored the performative process of making art through everyday materials and viewer interaction, inspired by popular culture and the political and social issues of the day. Highlights included Günther Uecker’s New York Dancer I (1965), a kinetic sculpture inspired by Sufi whirling created from nails imbedded in a column of loose fabric that whirls and sings when animated, and Rasheed Araeen’s Chakras I (1969–70/1987), which was a set of 16 bright orange, round pieces of wood that drifted along the Thames—a metaphor for the evolution of London as migrants changed the city—their river journey documented through photographs shown behind the wood slices on show.

The second chapter highlighted the United Arab Emirates, in particular pioneering Emirati conceptual artist Hassan Sharif and his students Mohammed Kazem and Ebtisam Abdulaziz. In the 1980s, Sharif explored the landscape of the UAE through his bodily actions, which were documented through photographs and writings in his “Performances” (1981–84). Also included were pieces from his series “Objects” (1982–2016), in which industrially produced materials are manipulated into various forms. His influence as the pioneer of Emirati conceptual art is clear in the work of his student and close associate Mohammed Kazem, who explores the dislocation of place using photography and video in his performance work Directions 2002 (2002), in which he documents his own performance of tossing wooden planks inscribed with GPS coordinates from the mainland of Fujairah into the sea. Ebtisam Abdulaziz’s Autobiography (03–07) (2007) is a video installation that follows the artist around the Emirate of Sharjah as she dons a bodysuit patterned with bank withdrawal dates and times as a map of her movements, a distillation of the human experience into commercial transactions.

In the last chapter of the exhibition, which focused on installations created in the 21st century, Egyptian artist Susan Hefuna’s video work NYC Crossroads (2011) looks at urban street intersections as a point of human interaction, accompanied by drawings created through a collaboration with choreographer Luca Veggetti of the movements of dancers in Notations (2011). She recreated a 2013 performance, Hefuna Chalk Drawing, on the gallery floor for the opening, her movements referencing those of Veggetti’s dancers. Anish Kapoor’s stunning time-based installation, My Red Homeland (2003), with its leaden black box attached to a motor gliding endlessly over the glossy, striated, wax surface painted red is monumental in its materiality, mass and scope.

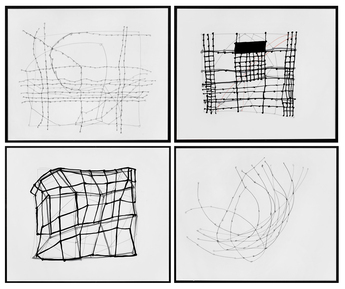

Completing this chapter was a site-specific installation mounted in multiple rooms by Dubai-based Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, a haunting dreamscape including collaborating with curators, artists and friends including Nargess Hashemi, Laleh Khorramian and Edward St. The multi-room work Another Happy Day (2016–17) comments on the commercialization of the art world, the process of creation, and pressing social and cultural issues. Rooms draped in crocheted webs are punctuated by artworks made by the artists and their friends, or drawn from their personal collection that includes creations of George Brecht and Mona Hatoum. The video installation by the artists at the center considers the forces that manipulate artists’ identities. In another room, objects and films by Fluxus artists are presented alongside installations by Hassan Sharif and Rose Wylie. In the final space, site-specific paintings on the walls and floor were a riot of colors and patterns, echoing the urgency presented in the moving pictures on the wall. This was particularly true in From Sea to Dawn (2016), which follows the treacherous path of migrants in Europe: video images manipulated the identities of migrants, and functioned as stark visualizations of the failure to respond to the most pressing humanitarian crisis of our time. The observer is immersed in the trauma, fear, discomfort and dislocation of contemporary life; its impression lingers and its impact remains.

“The Creative Act: Performance, Process, Presence” is on view at Manarat al Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi, until July 29, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.