-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of the entrance to “The Square: Part 3. 2019,” at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, 2019–20. Courtesy MMCA, Gwacheon / Seoul / Deoksugung / Cheongju.

A Spectacular History of Icons — “The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900–2019”

Set just before the Korean War through to its end, Choi Inhun’s novel The Square (1960) centers on the protagonist’s choice between the gwangjang (public square) and the milsil (closed room), metonyms for the respective ideologies of North and South. In the communist North, the ascendancy of the collective obliterates private life, while alienating individualism rules the South. Dissatisfied with both, the protagonist boards a ship bound for a “neutral” space beyond Korea. This seminal literary work was the namesake of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)’s sprawling 50th-anniversary exhibition at the institution’s Deoksugung, Gwacheon, and Seoul locations. With more than 400 works by nearly 300 artists, alongside extensive archival material, the three-part exhibition considered the role of art in the past century of Korean history, interrogating in particular the changing symbolism of the public square.

Split chronologically, “The Square” started at MMCA Deoksugung, within the historic palace complex in downtown Seoul. Immediately facing the entrance was People (1982), a monumental ink-on-paper depiction of a mass of tiny leaping human silhouettes by Lee Ungno. Though beyond the historical remit of the Deoksugung show, which spanned 1900–1950, Lee’s arresting piece aptly signaled the exhibition’s focus on Korea’s dynamic and diverse publics.

The exhibition properly began with the calligraphy and paintings by Korean literati during their anticolonial campaigns following Japan’s annexation of Korea. The Deoksugung show arguably had the most ideologically inflected trajectory, also covering the liberal-democratic and leftwing movements that flourished in the wake of the Russian Revolution and First World War, and ending at the dawn of the Korean War. The revisionist impulse surfaced most obviously in the interpretation of literati—elites from a long line of monarchists and isolationists—as not reactionaries but martyrs of the anti-imperialist cause, though curator Kim Inhye did well to emphasize this less in ideological than humanist terms. Chae Yongshin’s portraits, for instance, give the literati faces, whereas the recurring motifs of the four “gracious plants” (plum blossom, orchid, chrysanthemum, and bamboo, collectively symbolizing Confucian values of perseverance, integrity, and humility) in literati ink works, some painted in exile, signify an unfailing belief in honor worthy of respect.

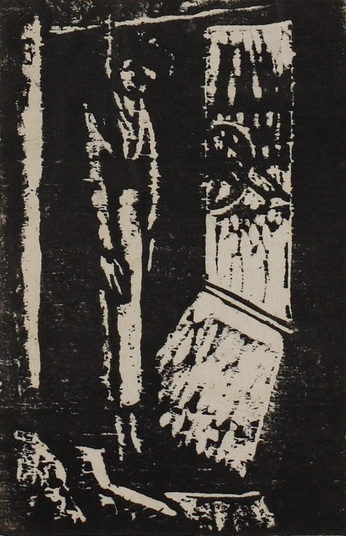

Beyond this revisionist chapter, the presentation took a commendably impartial approach to subsequent 20th century ideological groups, analyzing the way they found new aesthetic expressions by leveraging developments such as the availability of printing presses. In an exhibition with an overtly national focus, the excellent selection of 1920s and ’30s magazine illustrations by artists of the leftwing Korea Artista Proleta Federacio, rife with socialist iconography like the sickle and star, alongside Japanese artist Tadashige Ono’s woodblock prints of oppressed working classes, Death of Three Generations (1931), exemplified sweeping global ideological change, and the resulting solidarities that transcended national and ethnic lines. Strikingly, even as the exhibition moved on from the revolutionary zeal of the 1920s and ’30s to the bitter war years, it showed how artists continually sought to envision better futures, as in Lee Insung’s Sweet-briars (1944), of villagers at a rose bush, symbolizing the artist’s, and Korea’s, hopes for the metaphorical spring of peace.

At MMCA Gwacheon, Part II, covering 1950–2019, seemed to rely less on archival material and engaged more significantly with the distinct artistic potentials of reflecting or effecting change. In the former camp, South Korean illustrator Kim Song-hwan’s Korean War Sketch watercolors (1950) and Soviet Russian-Korean painter Pen Varlen’s depiction of the empty room where the 1953 Panmunjeom ceasefire talks took place are fascinating eyewitness accounts of historical importance within the war-art canon. Meanwhile, a display of 1950s black-and-white street photography by the likes of Limb Eung Sik and Lee Hyungrok evince the drab realities of postwar South Korea. Contrary to the documentary impetus of these works, non-figurative projects showcased new visual languages. The juxtaposition of Kim Whanki’s gorgeous, lapis-lazuli-hued abstraction Two Moons (1961) with the artist’s antique ceramic “moon jars” exemplifies at once the lasting influence of tradition on Korean artists as well as their will to reinterpret their cultural landscape and engage with Western modernisms.

It was also at MMCA Gwacheon that the exhibition got to grips with Choi’s central metaphors in The Square. A movement that flourished in South Korea during the tumultuous decades of military coups and authoritarian leaders (1960s–’80s), Dansaekhwa might be said to represent a retreat to the private milsil. With a focus on formal and material exploration, seen in Ha Chong Hyun’s and Park Seo-Bo’s innovative processes of repetitive mark-making, Dansaekhwa was, as curator Kang Soojung wrote, a means for artists to “segregate themselves from reality” in search of “de-materialized, spiritual worlds.” Yet if we consider the gwangjang and milsil not as fixed conditions but as polarities, we might say that the democracy movements of the 1980s marked a moment in which the South Korean populace was drawn to the square, a locus of collective power. The resurgence of overtly political art was shown, for example, with Choi Byungsoo’s colossal banner Save Han-yeol (1987), portraying the limp body of the student protestor who died after being struck on the head by a teargas canister at a demonstration in Seoul—part of the 1987 June Uprising that eventually toppled the military regime of Chun Doo-hwan.

New “squares” arose from the 1988 Seoul Olympics, a watershed representing South Korea’s ascent as an Asian Tiger in the global economic system (the mascot was in fact a tiger). Intricate models of stadia and archival promotional materials for the Games were presented alongside Kang Hong-goo’s photographic Greenbelt Series (2000–02), digital composites revealing the country’s rapid urbanization. Ancillary text explained that the modern infrastructure ushered in by the Olympics was made possible by the forced evictions of locals in Seoul neighborhoods slated for redevelopment, highlighting the ways in which public space might not be communal at all, but rather seized for national or commercial interests. An alternative “square” appears in Kim Heecheon’s video Sleigh Ride Chill (2016), a melee of dashcam footage, scenes from a car-race videogame, and creepy face-swap imagery to the artist’s voiceover musings on leaked sex tapes and an online suicide club, encapsulating the chaos of the virtual public sphere.

With such an overwhelmingly historical focus, “The Square” faced in its final chapter the conundrum of what to do when it caught up to the present. Staged at MMCA Seoul, Part III, by far the most diffuse exhibition, intended to offer contemporary perspectives on the division between public and private realms. Hong Seung-Hye’s BAR (2019)—a bench accompanied by a shelf with copies of nine commissioned stories by Korean writers inspired by The Square—was an on-theme sliver of communal space. Shizuka Yokomizo’s Stranger (1999–2000), a series of photographs taken through the windows of subjects’ homes after obtaining their permission via letters, is at once impersonal and uncomfortably intimate; two decades later, in an era of social-media over-sharing, Stranger remains more relevant than ever.

Unfortunately, relevance was an issue for a number of exhibits, including Eric Baudelaire’s Letters to Max (2014), a film about the artist’s contact with Maxim Gvinjia, ex-foreign minister of the autonomous region (and contested state) of Abkhazia in Georgia, displayed alongside Baudelaire’s letters. While the project itself is an interesting study of state sovereignty, its inclusion raised questions as to the curatorial parameters of a show largely devoted to the Korean context. Letters is not ostensibly related to Korea, and to draw a general conclusion from Baudelaire’s work about contested or divided spaces—which is pertinent to Korea—would be to neglect the specificity of the historical, ethnic, and geopolitical aspects at play in the Caucasus.

Although the final part felt like a curatorial loose end, “The Square” was spectacular as a history of modern Korea told through its symbols, from the spring blooms of independence to young Han-yeol, who became the face of a freedom movement. More remarkable still was the continuity of symbols: the plum blossoms in literati ink paintings are beautiful as ever abstracted by Kim Whanki; the fierce tiger embodying the Korean peninsula in an early 20th century silk map is tamed in Lee Manik’s silkscreen of the South’s friendly Olympic mascot. The MMCA’s visual history of Korea was a stellar investigation of the entwinement of image and ideas; how in some ways that relationship can morph with the exigencies of time, while in other ways, it doesn’t change at all.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

“The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900–2019” was on view at MMCA Deoksugung and MMCA Seoul until February 9, 2020, and at MMCA Gwacheon until March 29, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.