-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “The Voice of the Brush – Part II” at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, 2018. All images courtesy Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong.

While “The Voice of the Brush – Part I” looked at the pioneers of modern Chinese calligraphy, the final exhibition of the two-part series shifted its focus to the diverse directions that newer artists are taking.

Installation view of WEI LIGANG’s (left) Immersed in Calligraphy, 2014, Chinese ink and acrylic on paper, 180 × 96.5 cm; and (right) Qing Hai Zhan Yun, 2005, Chinese ink and acrylic on rice paper, 360 × 96 cm, at “The Voice of the Brush,” Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, 2018.

There was something awe-inspiring in seeing Wei Ligang’s “gold-ink cursive” stretch all the way up to the second floor of the gallery space. For Qing Hai Zhan Yun (2005), Wei combines lines from three different Song dynasty poems to create a poem of his own, relating the desperation and hunger that warfare gives rise to (the title describes the sea and the clouds as enshrouded in the adrenaline of impending combat). The work is a prime example of the way that Wei employs a mixture of the primitive, pictorial oracle bone script, and kuangcao, or wild script, in his calligraphy. Caught up in the spirit of destruction, there is no apparent structure in the way that Wei lays his words out across the page. Wei’s words, more often than not pushed far beyond the limits of legibility, test the truth to the idea that in calligraphy, the form of each word, down to the placement of every stroke, encapsulates the essence of the word—its connotations, associated imagery and so forth. When the viewer is unable to read the words at all, can any meaning be extracted purely from their aesthetic?

Installation view of HAO SHIMING’s Poetry by Wang Wei, Tang Dynasty, 2016, Chinese ink and color on silk, 27 × 27 cm each, at "The Voice of the Brush,” Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, 2018.

Similarly brimming with fervor are Hao Shiming’s ink and color on silk works. His writing looks as if it has been carved onto or even scratched out of the hard surface, their lines overlapping and criss-crossing with a frantic energy. Yet the even smoothness of these lines betrays a careful precision. In Poetry by Wang Wei, Tang Dynasty (2016), the words in the eponymous Tang poet’s “The Deer Enclosure” are laid out one by one on small square canvases, almost like a periodic table, containing the ordered chaos of Hao’s handwriting.

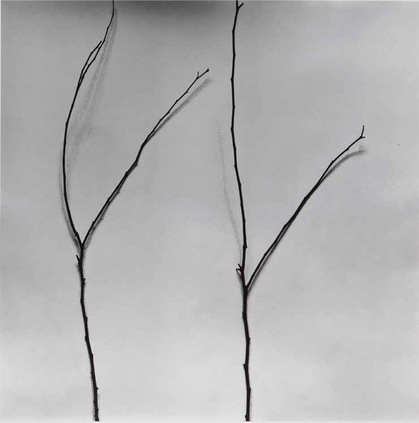

On either side of the gallery hung two square, gray-scale canvases by Chu Chu from her “Whispers of Trees” series (2011–17). Deceptively minimalistic in appearance, Chu Chu’s branches are photographed in black and white to mimic the appearance of traditional Chinese literati paintings. She traces the shadows in ink with lines of ancient poetry by the likes of Tang dynasty “Sage of Tea” Lu Yu, with writing so miniscule and faded that it is almost impossible to read even if one leans closer, as if in a long-forgotten language.

Lee Chun-yi’s artworks are perhaps the most breathtaking of the exhibition. Lee lightly stamps out excerpts from Buddhist scriptures on rice paper, then goes over the sheet in a dotted motion, building up the layers until the surface shows both the scripture and a landscape. The words materialize as one examines the image, as if evoked from contemplating the wonders of nature. Edges of the stamps form grids that frame the composition, modernizing the otherwise conventional aesthetic of these rocky, mountainous landscapes.

As the only European artist within the exhibition, Fabienne Verdier’s works show the influence of both Western art movements and her decade spent in China mastering the techniques of calligraphy. Traditionalists would be scandalized to learn how the French artist creates her gargantuan pieces: with waist-length “brushes” that can carry up to 68 liters of ink, suspended from the ceiling with wires, with two handlebars on either side that allow her to control the movements of the brush. Each broad stroke reflects not merely the flick of a wrist, but the movement of the artist’s entire body. In Colour Flows 4 (2012), black meandering lines dance across the dark teal canvas. The absence of written words or clear forms of representation—along with the painterly brushstrokes, fat globs of acrylic paint still visible—may give the impression that her artistic process is, above all else, intuitive. At first glance, there is perhaps more of abstract expressionism than Chinese ink art in the French artist’s paintings. But at the heart of her work—from the decisive arcs to the emphasis on movement—are the central tenets of classical Chinese calligraphy.

“The Voice of the Brush – Part II” was by no means a comprehensive overview of the current state of contemporary calligraphic art. The exhibition could have been more interesting had it not just vaguely gestured towards the enormous scope of transgressions in this field, but given it a unifying theme. It is, nonetheless, a fairly good start for those who are interested in the cross-pollination between contemporary Chinese calligraphy and other genres.

Phoebe Tam is an editorial intern of ArtAsiaPacific.

“The Voice of the Brush – Part II” is on view at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, until September 19, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.