-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Distributed between several themed gallery spaces across two floors of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, “Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora” comprised works by 17 artists of Japanese ancestry who are from or have lived in Latin America or Latin American communities in California, often referred to collectively as Nikkei—a term that applies broadly to Japanese emigrants around the world. Ample wall text provided contextualization for visitors who might not have access to a base of knowledge on why a population from the East Asian island nation migrated across the globe in the modern era, and how persons of Japanese descent in Latin America might identify themselves. Meanwhile, the works offered insights into the ways in which such artists have grappled with notions of assimilation and creolization.

Upon entering the first gallery, viewers encountered a gorgeously lit display of Los Angeles-based artist Kenzi Shiokava’s sculptural works and assemblages. Tall, sturdy poles were embellished with beads, tree bark, fiber and other organic materials. Shown alongside was the artist’s new photographic work, It is passing, changing indebtedly, irrevocably. . . (2017), featuring countless vintage snaps of couples, families, friends and forefathers. Shiokava is often associated with the “found-assemblage” movement, which was sparked by the self-determination that emerged from the Watts Uprisings of 1965. Debris collected from daily life accumulates meaning through Shiokava’s arrangements, which lovingly frame stories of hardship and joy experienced by those who have been uprooted and forced to build anew.

Hanging on the wall in the same room, Peruvian artist Eduardo Tokeshi’s soft sculpture Bandera Uno (1985) forms a bulky lump of red-and-white fabric that references the Peruvian flag, threatening to slide down from the canvas to which it is attached with taut strings. The sagging “bandera” seems to convey an understanding of national identity as one that is not fixed nor easily reconciled with one’s own cultural identity and history.

Visitors were then funneled through a series of galleries exploring themes like “Home and Homeland,” which delve into contemporary issues regarding borders and territories within and outside the Japanese diaspora. One wall text notes how from the Meiji era onwards, Japan was “forced into diplomatic and trade relationships with Western imperial powers,” necessitated by contact and exchange in the war-filled years, reminding the audience that the choice to migrate was not always prompted by an overwhelming direct desire by a majority. On the other hand, Mexican-born Taro Zorrilla interviews residents of Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo, in his video Dream House (2007). The subjects speak about their experiences as migrant workers in the United States as well as their dreams of constructing American-style homes. An accompanying installation realizes a doll-sized amalgam of that fantastical structure. Dream House also sheds light on the reasons why some seek to make dangerous crossings through impervious borders.

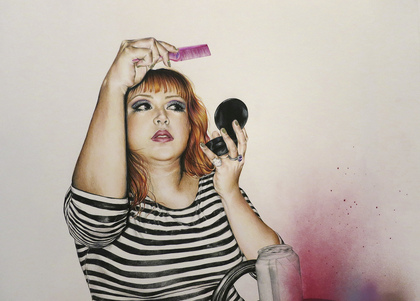

On the second floor, Mexican-born Yuriko Rojas Moriyama’s expansive installation features numerous vitrines that illustrate a genealogy of her family, as well as of the larger diaspora, juxtaposing narrative texts with historical artifacts such as a wooden desk from a local primary school that serviced the Japanese American community. Peruvian-born Patssy Higuchi’s painted triptych depicts bold, bright costumes, like clothing for an absent paper doll. In an interview, Higuchi remarked that most would not immediately recognize her as a Nikkei, which encouraged her to explore the disconnect between one’s representation and identity. Likewise, Los Angeles-based artist Shizu Saldamando’s finely detailed illustrations of Japanese-Latino cool kids speak to the hybrid multiplicities embodied by youth who engage in subcultures in a search for identity. The three artists’ ouevres delicately investigate the overlapping intersections of identity—including gender, nationality and culture, among others—that pose both questions and answers regarding how a person should be in the larger world.

The catalogue does not probe the specific works that are included in the exhibition, but instead compiles several thoroughly researched essays on diasporic intersections. Fascinatingly, as other outlets have noted, “Transpacific Borderlands” made didactic texts available in four languages: English, Japanese, Spanish and Portuguese. This decision reflects not only the ambition of the Pacific Standard Time initiative, which “Transpacific Borderlands” was a part of, but also the prominence of Western cultural influence and dominance of European colonial languages in the narrative of the Japanese-Latin diaspora. It would be remiss not to note that the confluence of cultures here is marked by an implicit erasure.

“Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo” is on view at the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, until February 25, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.