-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

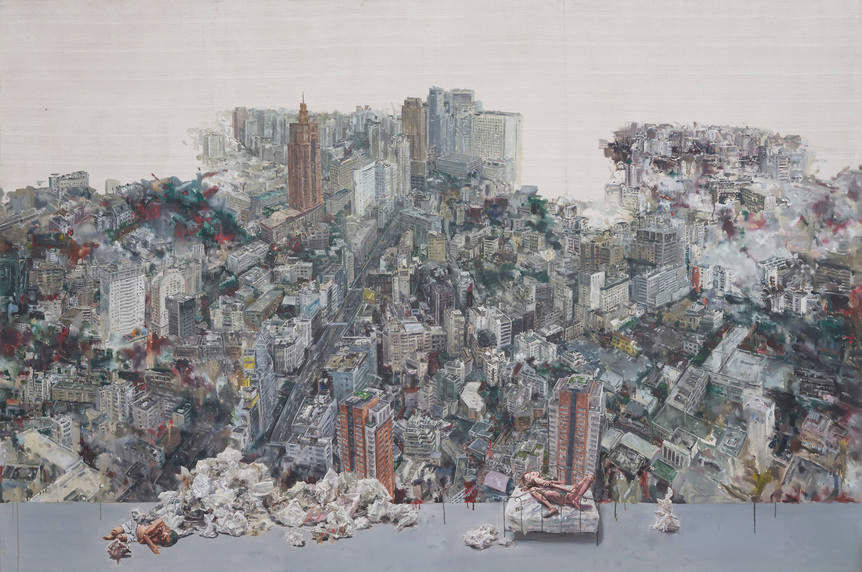

Installation view of TU HONGTAO’s solo exhibition at Lévy Gorvy, Hong Kong, 2020. All photos by Kitmin Lee. All images courtesy Lévy Gorvy, New York / London / Zurich / Hong Kong.

Near the entrance of Hong Kong’s Lévy Gorvy gallery was a panel of figurative and landscape sketches by Tu Hongtao, revealing the artist’s experimentation with composition and color, and his meticulous process. Meanwhile, the canvas opposite these drawings, Goddess of Luo River (2016–18), was, at first glance, non-objective—blue and yellow brushstrokes are interspersed among impastoed shades of green. The deliberate pairing of the sketches and painting is indicative of the exhibition’s strength. The presentation was a succinct showcase of the artist’s divergent oeuvre from the past 15 years, which has encompassed figurative cityscapes and expressive abstractions embodying Chinese traditions.

Goddess is inspired by Nymph of the Luo River, the now-lost handscroll by 4th-century scholar Gu Kaizhi, which chronicles the bittersweet romance between the female spirit and the poet-prince Cao Zhi. Tu’s interpretation is devoid of any figures save for the faint outlines of a lady near the bottom of the canvas. Instead, there are dynamic and vibrantly colored brush marks, reminiscent of rays of light shining on cascading waterfalls among rolling hills. In this way, Tu deconstructs the riverbank and waves that surround the couple during their encounter and farewell in the classic rendering, thus also blurring the physical and temporal boundaries of the original narrative.

In comparison, Tu’s earlier works hung nearby Goddess were surreal and theatrical. Chengdu, Tokyo or Shenzhen (2006), for example, renders a post-apocalyptic amalgamation of the three cities, with dense skyscrapers shrouded in heavy fumes, evoking the artist’s dismay with the side effects of rapid urbanization. In the foreground is a semi-nude and intoxicated couple, laying among heaps of rumpled paper. Disarray is likewise in Quiet World I (2006), which depicts melting figures and buildings—Tu’s frequently used motif. These works are part of Tu’s long-standing critique of consumer culture and the impoverished quality of contemporary life.

Tu relocated to the countryside of China following the financial crisis of 2008. Immersed in nature, he turned to an exploration of Chinese literati paintings and their utilization of white spaces and simple lines. These works are stylistically similar to Western abstractions and yet are Chinese in subject. For instance, A Horse of All Things (2014–18) stems from Zhuangzi’s idiom “life fleets as a white colt flits past a fissure.” The canvas is adorned with a horizontal band of abrupt red and yellow strokes against a pale blue, washed background. There are no horses to be seen, but from the charged brushwork, one can almost imagine a horse galloping across. Rooted in traditional Chinese shanshui paintings, these later pieces by Tu allude not only to natural sceneries but also to Tu’s own desire to leave behind a materialistic life. From his observations concerning society’s superficiality to his contemplations on humanity’s place in the world, Tu’s exhibition at Lévy Gorvy evidenced the artist’s diverse strengths.

Lauren Long is ArtAsiaPacific’s news and web editor.

Tu Hongtao’s solo exhibition is on view at Lévy Gorvy, Hong Kong, until June 30, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.