-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

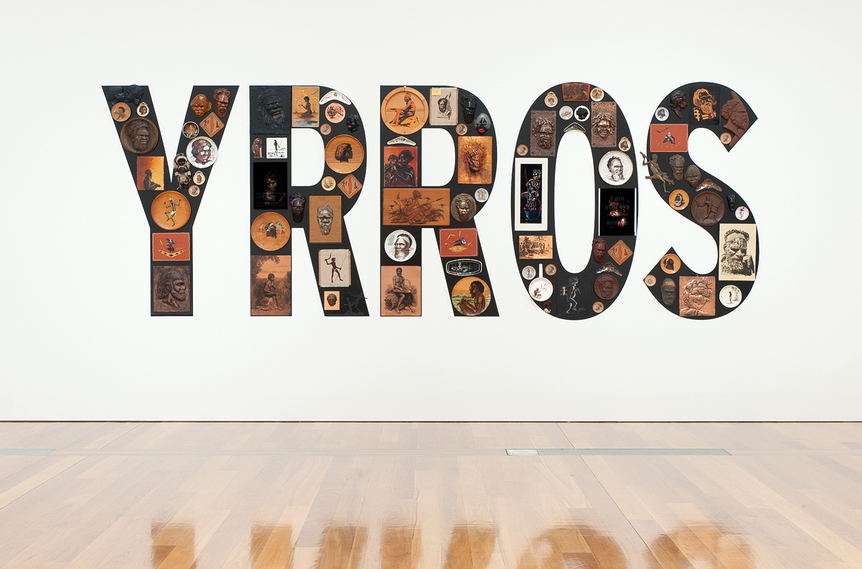

Installation view of TONY ALBERT’s “Visible” at Queensland Arts Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018. Photo by Natasha Harth. Courtesy Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

The name of Tony Albert’s first institutional survey is a play on the artist’s recurrent statement: “Invisible is my favorite color.” Titled “Visible,” it aptly conveyed Albert’s core artistic concern, namely a critical interrogation on the visibility of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australian society. Curated by Bruce Johnson-McLean and presented at Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, the thematically organized exhibition included examples of the artist’s distinctive object-based assemblages, paintings, photography and video works from 2007 to the present.

An iconic element of Albert’s practice is “Aboriginalia”—a term he uses to describe vintage homewares and bric-a-brac decorated with caricatures of Australia’s First Peoples, which he has been amassing since 1988. When displayed individually, these kitschy objects evoke different feelings dependent on the viewer, from nostalgia to sadness, curiosity, or anger. When grouped together, as in “Visible,” their effects were compounded and overwhelming. One of the exhibition spaces was dominated by a salon-style hang of Aboriginalia, drawn from Albert’s personal collection, while another group of these objects was spread on a nearby plinth around a mid-20th-century coffee table—a nod to the time period when these items were at the height of their popularity. Through such a display, Albert makes a powerful statement about how the First Peoples of Australia are seen—or not seen. Drawing out a common trope running throughout these artifacts were the installation of photographs from the “Mid Century Modern” series (2016), featuring ashtrays printed with caricatures of Indigenous peoples; and the text-based whiteWASH (2018), which comprises vinyl lettering spelling out the work’s title, studded with similar ashtrays. Through his process of collecting and examination, Albert had found that ashtrays were prevalent within the paraphernalia, noting: “There is something very metaphorical and symbolic about butting out a cigarette on someone’s face or culture.”

Further works combining Aboriginalia and text were spread throughout the exhibition. A significant example, the installation Sorry (2008), of vinyl words overlaid with an assortment of Aboriginalia, was created in response to the Australian prime minister’s formal apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008. This was a major moment in Australian history, whereby the government officially acknowledged and apologized for the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families. In contrast to the work’s early configurations, however, in “Visible,” the letters were installed backwards, thereby spelling “Yrros.” As Albert explains: “Flipping or turning things on their side is an act of rebellion. It is simple, it is intentional and it is clear.” The same gesture of reversal could be seen in Pay Attention (2009–10)—an arresting collaborative piece made by 26 Indigenous artists and Albert that demands both in legible order and as a mirrored-image: “Pay attention motherfuckers,” a blunt statement drawn from American conceptual artist Bruce Nauman’s 1973 lithograph, held in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. Nauman is a fitting reference for Albert, in the sense that he too is interested in language, specifically word play and the meaning and associations of readymade objects.

At the heart of the exhibition was Moving Targets (2015), made in collaboration with choreographer Stephen Page. Multiple screens are embedded onto different parts of a rusted car chassis, in turn illuminating the walls of the dark, enclosed space in which the multimedia installation was shown. Each screen shows a young First Peoples man with a neon-red target emblazoned on his chest, dancing increasingly fervently, except in the final scene projected from the boot of the car where the figure is shown still and lying down. The work takes as its departure point the police shooting of two Indigenous teenagers who were on a joyride through Sydney, and a group of young men who painted targets on their chests in protest of the racial profiling and police brutality towards their community. Moved by this gesture, Albert incorporated the bulls eye as a motif, noting, “a target takes away any invisibility—it highlights presence, defines the object within its scope.” Displayed in conjunction with the installation, and reinforcing the bulls eye as a visual signifier were examples from Albert’s photographic series “Brother” (2013), which portrays young Indigenous men with the same symbols emblazoned on their bodies. The motif, repeated across the two works, functioned as a powerful statement about how Australia’s First Peoples exist at the precipice between a distorted, perverse visibility and invisibility.

Addressing this imbalance by making visible the First Peoples in a meaningful way and negating the caricatures proliferated by Aboriginalia were Albert’s collaborative projects, one of the most poignant examples of which was the photographic series “Warakurna” (2017). This work depicts members of the Warakurna community posed and dressed like comic book superheroes. For the project, Albert worked with photographer David C. Collins and the children from the Warakurna community to come up with the concept and design. Albert’s collaborative practice was evidenced throughout the exhibition. The number of people that have been involved as co-creators in his works is indicative of how the artist believes in a shared vision, which reinforces the significance of his practice in contemporary Australian art. “Visible” was a fitting celebration of one of Australia’s most exciting artists.

Tony Albert’s “Visible” is on view at Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, until October 7.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.