-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of KEN LUM‘s "What’s Old Is Old For a Dog" at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, 2018. Photo by Phillip Maisel. Courtesy the artist; Misa Shen Gallery, Tokyo; and Royale Projects, Los Angeles.

Ken Lum, a Chinese-Canadian artist who has spent his adult life in the United States, is best-known for his exploration of the divisions navigated by the marginalized. This notion of rift—between the real and performed, between in-group and out-group—was writ large in “What’s Old Is Old For a Dog,” a survey of Lum’s work from the 1980s to present at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco. The gallery was bisected by a freestanding white wall to create two distinct parts. The first, which began outside the building with Lum’s now-famous billboard, Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1989–2018)—featuring a photograph of a smiling, bespectacled woman sitting in a cluttered office juxtaposed with the words in the title in block capitals—was brightly colored and generally comic in tone. The second part, hidden by the dividing wall upon entering, had a more muted palette, made extensive use of text, and was explicitly concerned with tragedy as a way of framing both individual lives and historical events.

Installation view of KEN LUM‘s "What’s Old Is Old For a Dog" at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, 2018. Photo by Phillip Maisel. Courtesy the artist; Misa Shen Gallery, Tokyo; and Royale Projects, Los Angeles.

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer notices a grouping of loveseats, end tables and lamps arranged in a closed square. Untitled Furniture Sculpture (1978– ) is comprised of high-end but ordinary and rather tacky furniture, such as might be found in a hotel. Pairs of gray and pale green cushions in conventional geometric patterns are arranged neatly on the overstuffed, black leather loveseats, while lamps with gray bases and beige lampshades sit atop end tables of colorless glass—an arrangement that is noticeably drab compared with the bold colors of the surrounding artworks. The furniture’s luxury, blandness, and inaccessibility refer to Lum’s experience as a child of working-class Chinese immigrants aspiring to an affluent lifestyle familiar only from catalogues—the sculpture at once tantalizes viewers with the promise of a soft place to sit and repels with its ugliness, while the closed arrangement prevents anyone from actually sitting on it.

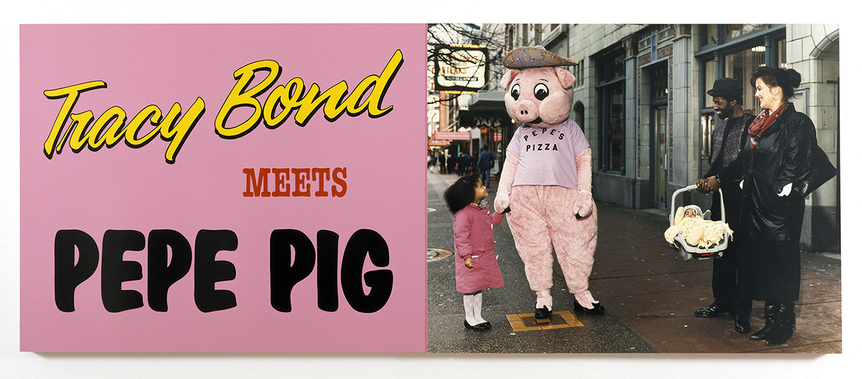

Decorating the walls surrounding Furniture were four of Lum’s neo-Pop diptychs. Like Melly Shum, Tracy Bond Meets Pepe Pig (1990/2018) and Boon Hui: Photography (1987/2018) feature a staged, blown-up photograph next to the work’s title in block letters. In Tracy Bond, a little girl in pink gazes ecstatically at a person in a pink pig costume advertising “Pepe’s Pizza.” The pig looks back at the girl, its expression unreadable.

On another wall, Jim and Susan’s Motel (2000) and Michael Hasson, Leaving Law (2001) imitate cheap strip-mall signage, with messages from the business owners spelled out in marquee letters. “CLEAN AND COMFY RMS. SUE, I AM SORRY. PLEASE COME BACK,” declares the text of Jim and Susan’s Motel, suggesting the breakdown of a heterosexual pairing that symbolically undergirds the heteronormative ideal of a mom-and-pop business. “Mike” of “Michael Hasson and Associates” simply announces that he is leaving his job because “THERE IS NO LOVE LEFT.”

The diptychs feature people in their places of work, performing professional selves that may be on the verge of breakdown or of collision with a more private self. Overall, the first part of the exhibition suggested an ambivalent relationship to the American experience—a simultaneous frustration with exclusion, and skepticism about the value of the social rules and norms on which that exclusion is based.

The second part of the show was made up of two recent bodies of works: “Tragic Philadelphians,” a collection of nine realistic bronze busts of real figures such as Billie Holiday and Nancy Spungen, arranged in two rows on a plinth, and “Necrology Series,” a set of textual posters about five feet high in the style of title pages from novels of the early 1700s, teasing viewers with sensationalized accounts of the fictional protagonists’ lives. The juxtaposition of real and fictional (but plausible) biographies raises interesting questions—are the real tragedies devalued by the comparison? Is the way we process the real and fictional essentially the same—as stories?

Both halves of the exhibition featured pieces that suggest narrative, with all but Furniture featuring named real or fictional people. The viewer is positioned as a consumer of the other selves encountered in the exhibit, invited to stare, to conjecture, and to pass judgment. While some of Lum’s works deal specifically with the experience of the economically and culturally marginalized, the exhibition’s strength was in its attention to identity in a broader sense—how we learn to read individual identities other than our own. As the title “What’s Old Is Old For a Dog” suggests, the identities on display are made legible by their positions relative to each other and the viewer, along racial, economic and cultural hierarchies.

Ken Lum’s “What’s Old Is Old For a Dog” is on view at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, until May 12, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.