-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Kurt Chan’s solo show “Why Not Start Again?” at Giant Year Gallery in Hong Kong was a collection of new drawings, sculptures and a mixed-media installation that reinterpreted traditional art practices in novel ways. Chan joined the faculty of Fine Arts department at the Chinese University in Hong Kong in 1989, but has recently retired from his tenure at the institution. Having earned his BFA at the same university in the early 1980s, he then moved to Michigan to hone his skills as a painter in an MFA program at the Cranbrook Academy of Art before returning to Hong Kong for a professorship. Although primarily trained in Western art practices, his most recent works reveal a fascination in the formal qualities of traditional Chinese calligraphy. In his curatorial statement, the artist wrote that during this turning point in his life, he chose to use this exhibition as an opportunity to “look back.” The exhibition marked an end to Chan’s career as an academic, as well as the beginning of his subsequent journey to practice what he had preached for nearly three decades.

Upon entering the gallery, one noticed that the show was divided into two sections. Leaning against the gallery walls, on clean white ledges, were calligraphic “paintings” that one assumed were ink drawings on rice paper. Upon closer inspection, it became clearer that the works were in fact digital drawings that perfectly mimicked the aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy, seamlessly combining soft feathering strokes with the artist’s darker, bolder lines. Within these modestly sized drawings lay idiosyncrasies—a face whose markings looked more like those of an intaglio scraper than a brush; impossible watermarks that had erased large sections of what was drawn underneath. These playful compositions were even iconoclastic in content; closer studies led to the realization that although the calligraphy resembled Chinese characters, they were mostly nonsensical abstractions whose compostions could only be deciphered in segements. In Chan’s own words, he aimed to deconstruct the connection between the “written form” and “designated meaning” in Chinese culture, using the Chinese brush as an abstrct artistic tool to explore how contemporary art can help us see traditional legacy with new eyes.

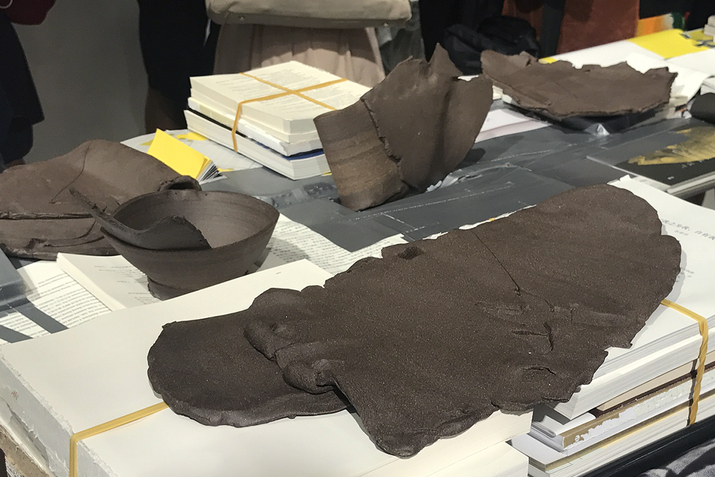

Probing the continued relevance of cultural genes that associate specific materials to their technique and carry the weight of visual tradition, Chan’s second type of work featured in the central gallery space was an installation of ceramic stoneware and readymade objects. Upon an ostensibly random selection of books—catalogs of art and design events, as well as monographs that cover East Asian art practice and education, writings on the cultures of the East and West, and stories of the salted fish industry in Hong Kong—sat an assemblage of roughly thrown, non-functional ceramic vessels that seemed to have solidified while spilling over their own weight. Thumbprints that record Chan’s labor and his sensitivity to touch can also be traced across the seemingly half-formed ceramic pieces, capturing his indulgence in the physicality and form of his new craft. His pluralistic approach to artistic mediums, use of visual puns and play with objects place him squarely within the Dadaist tradition, suggesting an inquiry into how such modern-day responses reveal our cultural preoccupations in the 21st century.

So what would one do when asked to begin one’s career anew? Not much is different for Chan, since using the language of the readymade to explore what contemporary art can do, and how it can be further interpreted within different cultural and spatial contexts, are what have always been driving his artistic practice. Since the early ’90s, Chan has written that he is not interested in the preservation or legitimacy of his artistic creations; instead, the artist focused on opening new paths for the development of alternative art, breaking down the hierarchy of values within the artistic tradition. He is someone who sees the potential in everything. For now, he juxtaposes the tradition of Chinese calligraphy with the modern-day technology of digital drawing, exploring pictoral semiotics with new and old visual tools to expand the margins of culturally bound visual expressions.

Julee WJ Chung is ArtAsiaPacific’s assistant editor.

Kurt Chan’s “Why Not Start Again?” is on view at Giant Year Gallery, Hong Kong, until September 8, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.