-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

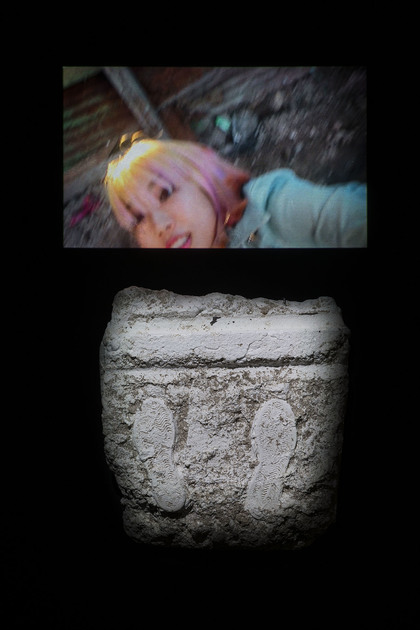

Installation view of CHIM↑POM’s archival installation 道 [Street], 2017, mixed media, dimensions variable, at “Why Open?” White Rainbow, London, 2018. Photo Damian Griffiths. All works copyright Chim↑Pom. All images courtesy Jamie Carter and White Rainbow, London.

Chim↑Pom, the Japanese art collective consisting of members Ryuta Ushiro, Yasutaka Hayashi, Ellie, Masataka Okada, Motomu Inaoka and Toshinori Mizuno, is best known for controversial public actions such as skywriting the word “PIKA”—meaning “flash” in Japanese—over the location in Hiroshima where America dropped the atomic bomb in 1945, or inserting likenesses of the disastrously stricken Fukushima Daiichi reactors into avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto’s painstakingly restored, Hiroshima-Nagasaki-themed Myth of Tomorrow (1969) mural in Shibuya.

Commentators are quick to apply words such as “subversive” or “anarchic” to artists that intervene in public space in this way, and while Chim↑Pom are fully deserving of these adjectives, it would be remiss not to recognize that beneath it all is a robust conceptual clarity and, in the engagement with legality and space that permeates “Why Open?” at London’s White Rainbow gallery, a searing but accessible intelligence that is all too often absent from the work of so-called “edgy” artists.

From the perspective of a visitor, the exhibition begins before even stepping into it. As part of a work titled Silent Bells (2017), pushing the gallery’s buzzer before entering triggers a corresponding doorbell to ring in an abandoned house in Fukushima’s no-entry zone, which, in turn, triggers a second tone to play in the gallery itself for the ears of visitors that have arrived before you. The poignancy of a doorbell ringing in a deserted house aside, at the push of a button, this work gives instant significance to a nexus of locations, and asks us to consider each of them in terms of presence and absence. Also suggested, of course, is the resounding question: if a doorbell rings and there’s no one there to hear it . . . ?

Inside, the gallery was kept in almost total darkness, with any light either illuminating or emanating from the exhibition’s three main pieces. One of these, The Grounds (2017), constitutes part of a larger work, The Other Side (2016–17), which is a response to Chim↑Pom member Ellie’s being denied entry to the United States. Having discovered a network of unofficial tunnels along the border on a subsequent visit to Tijuana, the group dug their own, and documented her treading not onto, but under American soil with a plaster cast of her footprints made there. A short film of her entering the underground passage and crossing the border was projected above the cast in the gallery. In addition to addressing the tensions between “here” and “there,” “inside” and “outside” already evoked in Silent Bells, the piece also poses questions regarding legality and its limits, with a derisory nod to the ways in which legal frameworks are superimposed over physical spaces.

Dimly lit in the center of the gallery was Is Artistic Exchange a Crime (2018), a three-meter slab of asphalt representing one of the group’s largest projects so far, Street (2017–18), for which they created an asphalt road extending from the entrance of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts to the actual public street 200 meters away. The work is a reference to the Sunflower Movement of 2014, during which students took over the Taiwanese Parliament for one month in 2014, and is based on interviews with some of those involved. In creating this new street, the group invited public contributions for how the space might be used, details of which were tellingly exposed in a small room adjacent to the main gallery, plastered with photographs capturing the work’s construction. In addition to these were framed documents pertaining to the regulation of the street, each headed with a request for an activity to be permitted, followed by the discussion surrounding it and the decision regarding its licitness. Each of these negotiations was humorously illustrated on a scale model of the museum, surrounding area and street. The most amusing example, and perhaps the most pertinent with respect to how morality, legality and spatiality interact, regarded public obscenity, and was illustrated on the model with an explicit cartoon, captioned: “No sex in the public space . . . except for romantic love act . . . ”

Back in the main exhibition space, this brilliant crassness could be found again in the title of the new work, Asshole of Tokyo (2018), in which the group project what they saw when they opened a Tokyo manhole cover onto the gallery wall. The work bears further suggestions of a controlled space transgressed, but, unexpectedly, it is most notable for its formal qualities. While it has all the implicit urbanism of countless works by street artists, and the hypnotic depth and dirt of a work like Damien Hirst’s Black Sun (2004), the piece has a raw texture that many of these artists try often and in vain to achieve, something that seems to come honestly and effortlessly to Chim↑Pom.

Ned Carter Miles is the London desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Chim↑Pom’s “Why Open?” is on view at White Rainbow Gallery, London, until July 7, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.

![Installation view of CHIM↑POM ’s archival installation 道 [Street], 2017, mixed media, dimensions variable, at “Why Open?” White Rainbow, London, 2018. Photo Damian Griffiths.](/image_columns/0033/9135/3_cp_wo_7_863.jpg)