-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Women in Art: Hong Kong” at the New Hall Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, 2019. All photos by Wilf Speller; courtesy New Hall Art Collection.

Within the United Kingdom, all-women exhibitions have become de rigueur for public and private galleries alike, from Tate Britain’s display of female artists spanning the past 60 years, to Richard Saltoun Gallery’s “100% Women program.” Yet, are such exhibitions inadvertently tokenistic? What responsibilities do curators have to go beyond simply labelling women artists by gender, as if male artists are the default? “Women in Art: Hong Kong,” at the New Hall Art Collection in the all-female Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, made a case for the women-only show by combining gender-based marginalization with wider political tensions. Catalyzed by curator Eliza Gluckman and researcher Phoebe Wong’s findings on the alarming lack of visibility afforded to female artists based in Hong Kong, the exhibition attempted to rectify this situation by bringing together seven of them to reflect upon the past 50 years of socio-political and artistic change in the former British colony.

Opening the exhibition were Fang Zhaoling’s ink paintings Deep Autumn (1974–77) and Terraced Fields (1981). During Fang’s lifetime, privileged women artists were often stereotyped as “boudoir painters,” limited to depicting interiors, flowers and birds for leisure. Yet Fang, who studied under modern master Zhang Daqian, became one of few women working within the traditionally masculine territory of Chinese landscape painting. The two sweeping landscapes on view are testament not only to Fang’s skill, but her challenge to the gendering of art forms.

Beyond Fang’s paintings, the exhibition showcased predominantly works created in the last decade, many of which focused on the tensions between Hong Kong and mainland China. Jaffa Lam’s sculptural installation Save a Star in your Spittoon (2015) took inspiration from a famous photograph of Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping discussing the handover of Hong Kong in 1984. At Deng’s feet was a spittoon, which some surmise was meant to throw off the British prime minister. Lam transformed the spittoon into a lamp by attaching lights inside the object. The opening was covered with a star made from fragments of umbrella fabric, referencing Hong Kong’s 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. Lam’s work spoke to the sense that the wish for a democratic Hong Kong will never be respected by the Chinese Communist Party. Elsewhere, Au Hoi Lam expressed a similar feeling of uncertainty with Hong Kong, Hong Kong (2016). Depicting a faintly sketched map of the Pearl River Delta with an empty space at the bottom, the painting cautions against the gradual erosion of Hong Kong’s unique identity as China tightens its grip on the region.

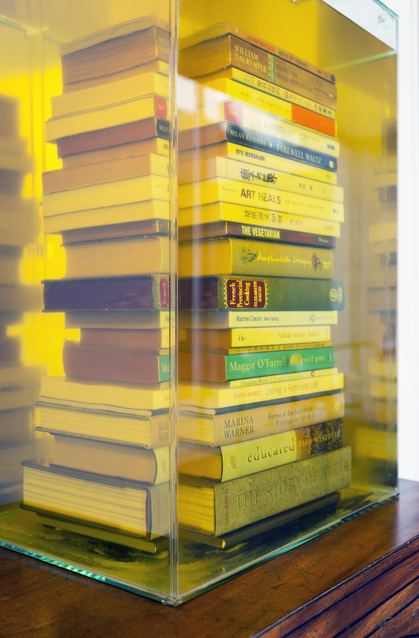

Next to Lam’s work was Choi Yan Chi’s installation Drowned Books (2019), in which 24 volumes are submerged in vegetable

oil, thus paradoxically “preserving” (in a culinary sense) and destroying (in a practical sense) the knowledge contained within them. Choi has created a number of such installations since the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, which marked the end of a period of relative outspokenness against the authoritarian regime. In this version, the books were selected by women from Cambridge and Hong Kong, contrasting a renowned place of learning with a city that is readjusting to growing censorship.

Mediha Ting’s painting Orange Land Green Void with Leon Sign (2010) and Ko Sin Tung’s mixed-media print Express (2015) both comment on the relationship between Hong Kong’s urban landscape and its identity. Tang’s depiction of brightly colored neon signs—a fast-disappearing fixture of Hong Kong’s cityscape—provoke feelings of nostalgia, as well as the artist’s personal sense

of linguistic estrangement, conveyed by overlaid, barely legible snippets of text from online chats and local slang. Ko’s more ambiguous work features a blurry image taken from the Express Rail Link, which connects Hong Kong to Guangzhou and Shenzhen. The image is further obscured by a strip of yellow washi tape. Physically obstructing the viewer from seeing, Ko alludes to the unknown future of Hong Kong and its relationship with mainland China.

“Women in Art: Hong Kong” was a long overdue, if necessarily limited, attempt to fill art historical gaps, and a timely reflection on the context in which the selected artists work today.

“Women in Art: Hong Kong” is on view at the New Hall Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, until July 31, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.