-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of FRANKLIN CHOW’s Untitled, 2007, seven works created with xuan paper, wire, ink and varnish, each 250 × 50 × 25 cm, at “Zigzagging My Way Home,” Powerstation of Art, Shanghai, 2018. All images courtesy the artist and Powerstation of Art.

Franklin Chow’s Shanghai debut, “Zigzagging My Way Home,” at the Power Station of Art (PSA), was a mini-retrospective of sorts. Held in a small subdivided gallery of the cavernous former Nanshi Power Plant, the tightly curated display encompassed materials ranging from Chow’s late-1990s journal drawings to installations made over the last five years, brought together by the head of the PSA’s exhibition department, Xiang Liping.

Although little known in the faddish Chinese art world, the show was a homecoming for Chow. Now in his early 70s, the Shanghai-born artist grew up in Hong Kong and studied art in Paris—where he mixed in similar creative circles as elder Chinese émigré artist Zao Wou-ki—before moving permanently to Switzerland. Chow’s family were experts in the field of traditional Chinese art and culture. His larger-than-life father, Edward T. Chow (1910–80), was a legendary Hong Kong collector-dealer of Chinese antiquities, principally ceramics—four of the pieces from his father’s collection in the Shanghai Museum that inspired his work were on loan for his show. His transnational upbringing, however, meant that he was also exposed to mediums such as readymades, video and installation. These wide-ranging visual languages led Chow to meld tradition and experimentation. Prevalent among the exhibition’s most visually stunning works were his shuimo paintings, where ink was mixed with oil paint and glaze to make what could have been static, oppressive canvases glide and dance. Similarly, in two Untitled works (2004, 2014), hessian fabric—made from jute—and wooden cane strips that are stretched across the frame almost like a string instrument, magically transform his ink paintings into understated, geometric compositions.

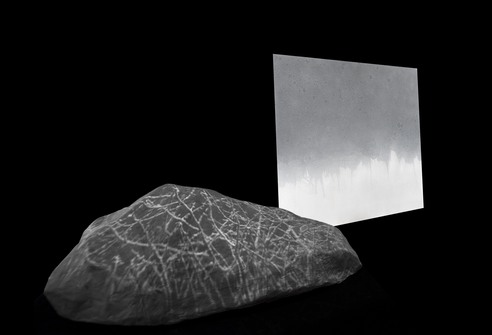

Placed among the minimalist canvases and works on paper were a variety of sculptures and installations, bearing witness to Chow’s life in Europe and his background in film production and advertising. From 1964 to 1970, Chow lived between Paris and London, where he worked in cinema and fell in love with the aesthetics of film noir, particularly the emphasis on light and shadow, which is evident in his ink works. This early influence also shows up in his meditative video installation Summer Snow (2008), where Chow projected footage of snowfall on a large stone in a dark corner of the gallery. In the center of the largest room was an impressive installation of what appeared to be charred books. Arranged in a large grid, Blind Prose (2007) is comprised of 50 books soaked in dark black ink. Upon first glance, it would appear that the text is illegible. But when examined closely, the books reveal its text can indeed be read—the pages are printed in braille. Blind Prose riffs on Chinese literati traditions of ink that comprise the “three perfections”: poetry, calligraphy and painting—and it is this work that shows the cultural hybridity that Chow has managed to negotiate with ease.

Installation view of FRANKLIN CHOW’s Journal, 1997– , drawings and paintings, each 41 × 38 cm, at “Zigzagging My Way Home,” Powerstation of Art, Shanghai, 2018.

After marrying and starting a family in 1969, Chow cofounded a creative advertising agency that was later acquired by Saatchi & Saatchi. It was only in the early 1990s that he decided to return to art. In 1997, he began an illustrated journal that he compiled daily. A selection of 108 pages from the last two decades covered the far wall of the galleries. The extracts reveal Chow’s inner thoughts, daydreams and insecurities in handwritten, stream-of-consciousness prose, with statements such as: “Sometimes, I don’t write anything in my journal because I don’t know what to write. The details speak for themselves so I write nothing.” Shown alongside were expressionistic ink doodles of two-headed figures hanging delicately by a frayed piece of string and a man lifting off his mask. These drawings were perhaps references to Chow’s own dualities—a Chinese expatriate artist living in Lausanne, a successful businessman who abandoned and then re-embraced his artistic sensibilities, or even a son stepping out from the shadow of his famous, imposing father. Far from being defined by his family’s legacy, the exhibition celebrated Chow as an artist in his own right—one who deserves a place in the fascinating history of Chinese émigré artists in Europe, who have weaved their Chinese heritage together with Western influences, often with moving effect.

Elaine W. Ng is the editor-in-chief and publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.

Franklin Chow’s “Zigzagging My Way Home” is on view at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai, until October 17, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.