R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “How To See [What Isn’t There]” at Langen Foundation, Neuss, 2018–19. Photo by Bettina Diel. Courtesy Burger Collection, Hong Kong.

In “How to See [What Isn’t There],” curator Gianni Jetzer offered a reflection on one of the most perplexing aspects of human life: the reality of absence, and its translation into artistic practice. Presented at Neuss’s Langen Foundation, a private museum designed by Tadao Ando on a former NATO base, the show featured works from the past 20 years by 32 international artists, all of which are part of the extraordinarily eclectic Burger Collection, Hong Kong. Through a division into five chapters, Jetzer provided a loose thematic ordering for works that neither share a single category of artistic production, nor one mode of representation. Although not explicitly discussed, the show also opened up parallels to earlier conceptual confrontations with the notion and possibility of absence, such as John Cage’s silent composition 4’33" (1952), Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) and Robert Barry’s pencilled statement All the things I know but of which I am not at the moment thinking – 1.36 pm, June 15, 1969 (1969).

Among the highlights of “How to See [What Isn’t There]” was Kris Martin’s Altar (2014), a metal triptych that towers over Ando’s post-modern landscape outside the main building. Modelled on the Ghent Altarpiece (1432), attributed to Hubert and Jan van Eyck, Martin deprives his Altar of any representational sacred content and spiritual potential, while making a mockery of the liturgical calendar that in van Eyck’s time would determine whether the side panels had to be opened or closed. Martin enters into blasphemous harmony with Ando, whose self-proclaimed aim was to confront people and nature without any God standing in the way. As a commentary on the Pyrrhic victory of our secular age, Altar announces the dialectic between deprivation and potentiality that ran through parts of the show as a variation on the theme of absence.

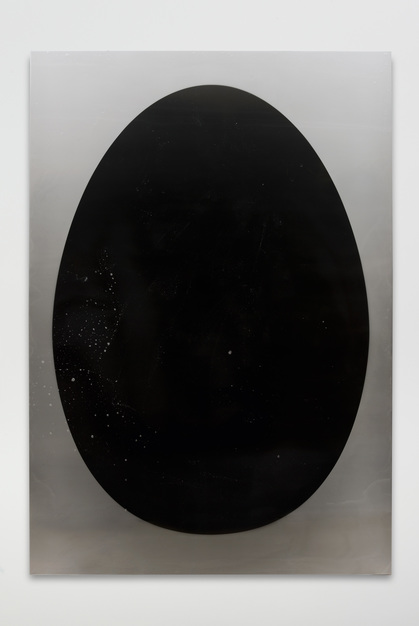

Inside the main galleries, Fabian Marti’s depictions of egg shapes seem to defy human intention through abstract universality. That is, until one learns from their titles the artist’s deep need for spirituality or whatever might function as its cheap yet sufficient secular substitute: Deep Egg (unless life is a dream, nothing makes sense) and Deep Egg (something out of nothing), both from 2016. Marti’s aesthetic commentary on the human need to ascribe meaning (in this case, to the shape of an egg) reflects Friedrich Nietzsche’s psychological insight at the end of his book, On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), that “man would rather will nothingness than not will”—Marti, perhaps the Nietzschean bandit of the show.

The exhibition at Langen greatly benefitted from the Burger Collection’s diverse representation of Chinese and Southeast Asian artists. At a time when China reflects on 40 years of reform, which has led from the absence of prosperity to the near absence of poverty, Wang Du’s bronze sculpture China Daily – IMF chief confident on China (2007) points to China’s rise in the global capitalist order and its struggle for recognition amid what Western political discourse presents as “the threat of China.” Wang’s gesture of crumpling the party’s English newspaper expresses the tension between a nation’s search for moral orientation through global economic success and the absence of moral absolutes under the conditions of an ongoing deconstruction of whatever appears to rest on an outdated normative order. Similarly, Zhang Huan’s sculptural Ash Portrait No. 28 (2008), made from the remnants of burned incense, reflects the place of China’s cultural tradition and its response (or lack thereof) to national collective memory. How does China portray itself under fast changing material conditions and in the absence of a renewed collective moral vision?

“How to See [What Isn’t There]” demonstrated that the reason we can never fully comprehend absence lies not in some flaw of human perception, but owes to the complex meanings we assign to the absence of memories, persons and experiences. The show was not driven by efforts to neatly fit an ambitious assemblage of works under the rubric of absence. Instead, it provided an open space for an exercise in seeing—a kind of seeing that by its very nature reaches beyond the visible. The show afforded viewers the freedom to question one’s relation to what is currently absent but may well become part of aesthetic, moral and political imaginations. A rare opportunity.

“How to See [What Isn’t There]” is on view at the Langen Foundation, Neuss, until March 17, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.

![Installation view of WANG DU’s China Daily – IMF chief confident on China, 2007, bronze, 125 × 210 × 135 cm, at “How To See [What Isn’t There],” Langen Foundation, Neuss, 2018–19. Photo by Bettina Diel. Courtesy Burger Collection, Hong Kong.](/image_columns/0039/4547/3a__installation_image._how_to_see__what_isn_t_there__at_langen_foundation__9_sept_2018_-_17_mar_2019._photo_credit_bettina_diel._courte__11__715.jpg)