R

E

V N

E

X

T

Eungie Joo, curator of Sharjah Biennial 12, 2015, giving opening introductions to March Meeting 2015. All photos by Kevin Jones for ArtAsiaPacific.

March Meeting 2015: (Day 1) Metaphors Form A Geography From A Shadow

The Sharjah Art Foundation’s annual March Meeting, exceptionally occurring in May this year, is governed by a simple organizational conceit: artists are invited to curate the discussions. The Meeting forms an integral part of this year’s Sharjah Biennial: curator Eungie Joo, at the Meeting’s helm again this year, devised the 2014 March Meeting under the banner “Come Together”—days of talks and performances that fed into Sharjah Biennial 12’s theme of The past, the present, the possible. Casting an eye across the coming four days of programming—orchestrated by curators Rasha Salti and Kristine Khouri, Eric Baudelaire, and artist-duo Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri—there is no sensation that 2015’s Meeting, in any way, bookends or “wraps up” the Biennial, unlike how last year’s sessions contributed to its genesis. Rather, the Meetings present themselves as a bit of a trove, a stockpile of conversations and encounters with the potential to veer off in multiple directions. As the curtain went up on day one, it seemed hard to know what to expect.

Salvaging, then, seemed an appropriate enough thread for the day. From shows and institutions that have slipped through the cracks of art historical memory, to the potentially lost spirit of activist communities, to art history itself as a mechanism of salvage, the first day was about digging, excavating and asking “Why now?”

Rasha Salti and Kristine Khouri, who took the March Meeting stage in 2014 to discuss their research project around a “lost” Palestinian exhibition, returned this year to discuss their exhibition of that same Palestinian show or, more precisely, how they transformed their research into an exhibition of its own. “Past Disquiet,” currently showing at Barcelona’s Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, tells the story of the 1978 “International Art Exhibition for Palestine” in Beirut, a show that seemingly vanished with no archival trace. The seed collection for a proto-institution—a sort of Palestinian museum in exile—the 1978 PLO-orchestrated show comprised some 200 works by 200 artists from 30 countries. Armed only with a photocopy of the catalogue as sole evidence of its existence, Salti and Khouri embarked on a five-year research journey that unearthed a network of artists galvanized by the Palestinian cause. Among them, artist Claude Lazar—active in the anti-establishment Salon de la Jeune Peinture movement, and a dedicated PLO supporter at the time of the 1978 show—unlocked his carefully guarded mother lode of show-related documentation that helped the subsequent pieces of the exhibition puzzle fall into place. “I have been waiting for you for 30 years,” he told the sleuthing curators on their first visit.

Putting aside the intricacies of spatially reconstructing this ephemeral event, and its obvious contribution to the exceedingly sparse corpus of exhibition history (particularly non-Western exhibitions), what seems critical in Salti and Khouri’s work is having pinpointed an alternative history of artists organizing shows in parallel to public institutions and the art market at the time. The pro-Palestinian show was perhaps a product of a time of vocal expression against injustice—specifically anti-imperialism, but also anti-Vietnam, anti-Pinochet, anti-apartheid—and, as such, was the fruit of a solidarity expressed in the idea of the museum in exile.

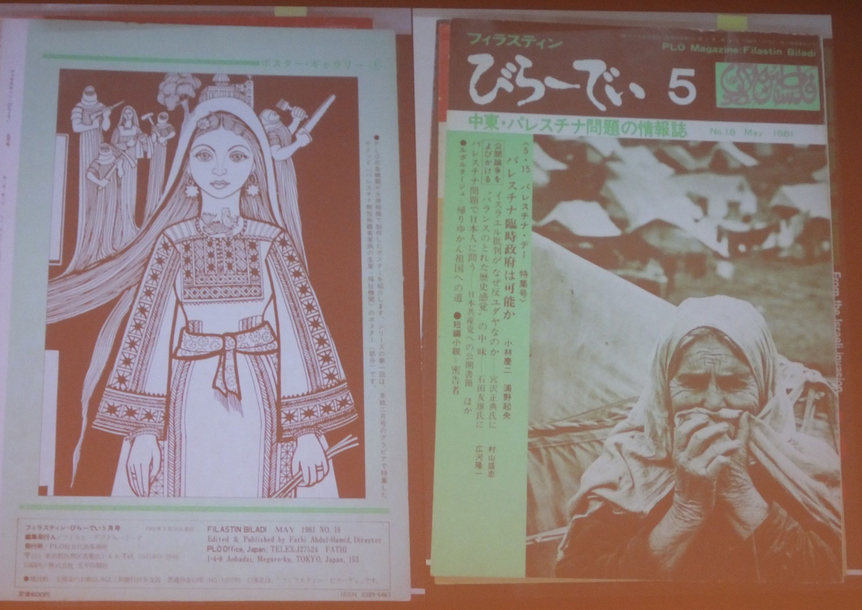

Having discovered that an inordinate number of Japanese artists contributed work to the 1978 Beirut show, Khouri took the relay from Salti to delve into the reasons behind this brisk Nippon participation. She told the tale of JAALA (Japan Asia Africa Latin America Solidarity Committee), an anti-imperialist, anti-war, anti-nuclear Japanese organization focused on the Third World. Spearheaded by a darkly charismatic art critic, the late Ichiro Haryu, the association was a bit of a bellwether of pro-Palestinian sentiment in Japan. Khouri’s narrative embraced the enterprising PLO office in Tokyo, Arafat’s 1981 Asian Tour with his Tokyo stop, a monthly magazine titled Philistine Baladi (complete with pithy Arabic lessons for Japanese readers), Arabist academics, Japanese activists’ visits to camps in Beirut and even a Tokyo version of the 1978 Beirut show. The entanglement was deep and the solidarity strong. Unearthing the strands of that solidarity, and discerning what it actually looked like at the time, was the task set by Khouri’s conversation with Mei Shigenobu, daughter of Japanese Red Army founder Fusako Shigenobu, herself an avid supporter of the Palestinian revolution.

WJT Mitchell’s concluding talk ricocheted off the excavation of the 1978 exhibition to focus less on international support for the “unfinished revolution” in Palestine that the show roused (or spotlighted), rather than an imagined collaboration between Palestinians and Israelis through exemplary partnerships between artists on either side of the colonizer/colonized divide. Evoking the failed collaboration between Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata and Israeli art historian Gannit Ankori, Mitchell moved into a succession of examples across painting and film, culminating in art as social practice to examine a single-state solution through the prism of art. At once inspirational and polemic, his vision left one major question unanswered: once we see what we can learn from art (in this case harmonious collaborations), how do we extrapolate it to the wider world?

March Meeting 2015 is taking place now until May 16, 2015, at the Sharjah Institute for Theatrical Arts.