R

E

V N

E

X

T

ERIC BAUDELAIRE (left) and HASSAN KHAN (right) discussing Baudelaire’s film Letters to Max (2014) during the second day of March Meeting 2015, Sharjah. All photos by Kevin Jones for ArtAsiaPacific.

March Meeting 2015: (Day 2) The Sharjah Sessions—Discussions Curated by Eric Baudelaire

If he were not the “Anambassador of Abkhazia,” Max Gvinjia would most certainly be a philosopher. But Max’s duties as roving representative of the widely unrecognized “stateless” Caucasus state keep him busy on an international scale. One such responsibility is taking appointments in the itinerant Abkhazian Anembassy, responding to visitors’ questions with smooth diplomacy and philosophical maxims tinged with melancholic resignation (“War is like rain; people get used to it”). Enlisted into The Sharjah Sessions, Paris-based American artist Eric Baudelaire’s multi-part project for March Meeting 2015, Max sat down for a public session with Egyptian artist Hassan Khan. Their conversation kicked off a day of occasionally passionate interrogations regarding the divisive notion of the nation-state. Abkhazia’s liminal condition (a physical but no legal existence) was a springboard for a broader romp through all manner of “imagined states,” stretching well beyond Abkhazia’s humble borders.

“I am probably the first Abkhazian you have ever seen,” Max asserted from his seat on stage. The former Foreign Minister of Abkhazia, Max dabbled in acting as a young man—the best way, he insists, to learn to be a politician. Although he is questioned by fellow Abkhazians concerning his current role as Anambassador (“How could you agree to be part of an exhibition?”), Max makes no distinction between a recognized political role and an unrecognized one. As he glided around Khan’s burrowing questions, Max seemed inhabited by some breed of earnest theatricality. On this stage in Sharjah’s theatrical institute sat an off-the-record ambassador from a virtually inexistent land (only seven countries officially recognize Abkhazia, three of which are unrecognized themselves), who discussed issues of statehood (“All states are temporary”), his country’s happiness quotient (“It should be a goal”) and nationalism (“Nationalism is like fast food”) in a discourse that was at once polished and sincere. Although much remained unsaid (the plight of Georgian exiles, the new government that fired him from his ministerial role), Max, perhaps like Abkahzia itself, was reassuringly genuine, and yet somehow seamlessly staged.

If Abkhazia is a state without a state, Baudelaire’s film Letters to Max (2014) is a documentary without documents—a single, subjective “oral history” (specifically, that of Max) with no archival footage and very little literal correspondence between text and image. “Observational,” Khan described the film. “Theatrical,” countered Baudelaire. Theatricality, the filmmaker argued, is the very nature of the nation—which is a collective fiction, as much for what its people remember together as for what they forget. Over the course of their long collaboration, Baudelaire sent 74 letters to Max in Abkhazia, of which only 50 arrived due to the country’s liminal status. “Each letter has its own destiny,” philosophizes Max in the film. “They may come or they may not come.” A slow, deliberate melancholy pervades Letters to Max—forlorn clusters of bland furniture in inky interiors, scabby ruins strangled by conquering plants, shoddy amusement parks and stilted rehearsals for a military parade of gangly teens. Sidelining questions about the veracity of the documentary image, Baudelaire sees fiction not only as part of the film’s vocabulary, but something that is deeply wound up in state-as-theater, particularly in Abkhazia (where ministries are peopled by diplomats with no diplomatic relations), with Max as the ultimate actor/politician.

I was looking forward to The State of State, as it was the March Meeting’s first multi-voiced panel—a three-way conversation rather than the dialogues or monologues that have prevailed in its other events. However the poly-vocality came less from the panelists than from the questions one of their presentations sparked among the audience. If the contested worth of the nation-state had been simmering below the surface of the morning’s conversations, it erupted in the afternoon’s proceedings. Historian, political scientist and associate professor at the Lebanese American University of Beirut, Fawwaz Traboulsi looked at the nation-state through the prism of Sykes-Picot and the Balfour Declaration in a presentation that seemed like a vast historical fresco of the region—from Ottoman territorial patchworking to Isis’ globalization. Championing a model of confederation of the Arab states similar to the EU (on the condition of a de-Zionized and de-nuclearized Israel), his fiery history lesson was challenged on questions of the success of revolutions, the failure of language to capture the subtleties of nationalism, the appropriation of revolution-inspired cultural production by counter-revolutionary forces, and other burning topics.

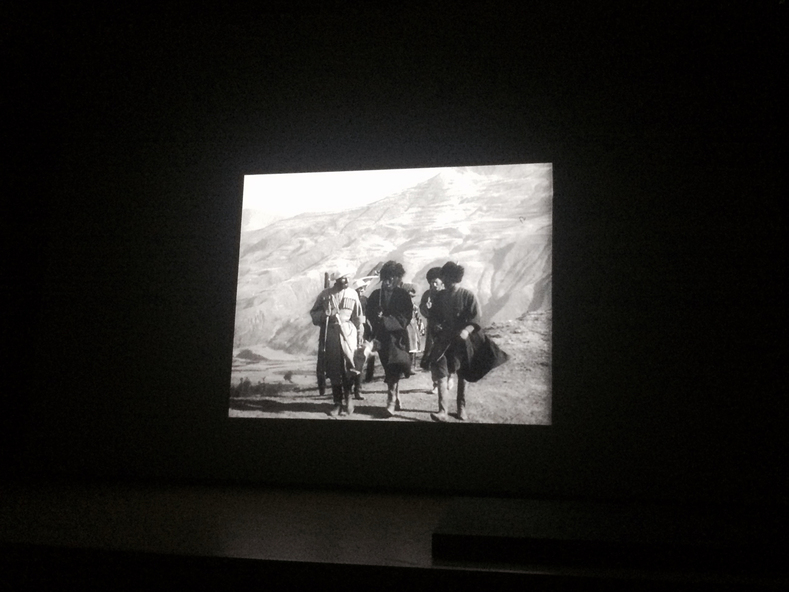

As The State of the State’s fires subsided, the lights dimmed on Eliso, a 1928 silent film by storied Georgian director Nikoloz Shengelaia. If Letters to Max knowingly omitted the Georgian voice from an Abkhazia-centric view of geopolitics, here it was to round off the day. A story of young love mired by class and religious barriers is secondary to the tale of the Russian “pacification” of Georgia in 1864, with the buffoonish Tsarists scooping up arable land as snaking caravans of peasants hit the road to deportation. Resistance, collective bonds, retribution and, yes, exclusion seemed to be the fixings the ousted peasants took on the journey to their next political chapter.

With the Georgians winding below the towering mountainous scene, another landscape beckoned at the Sharjah Institute for Theatrical Arts, where the films were screened. Souls’ Landscapes: Violence, Magical Superstructures and Invisible Guardians—a hypnotic performance by percussionist Uriel Barthélémi.