R

E

V N

E

X

T

The curtains closed on the 2017 March Meeting and Sharjah Biennial 13’s opening-week program with a quiet number. Dubai’s own art week, with a gallery night in Alserkal Avenue and Art Dubai had lured many people away to the neighboring emirate or kept them out late. The final program in Sharjah featured four March Meeting correspondents who gave individual presentations about their own research or curatorial projects. It began with Gökcan Demirkazık, a research assistant at Istanbul’s Salt, who talked about ongoing research into how landscape figures into modern and contemporary Turkish art. Nadine Attalah then presented about the projects of Madrassa Collective, whose members hail from countries including Tunisia, Cameroon, Morocco, Algeria, Syria, Egypt and Nigeria. Attalah explained that the group has no physical space nor even a web-platform but uses exhibitions themselves as their “place of gathering” to skirt many of the difficulties that come from being a transnational group. Renan Laru-an, director of the collective DiscLab – Research and Criticism, in the Philippines wove together historical anecdotes about institutions in the Philippines. Finally Berlin-based artist and filmmaker Aykan Safoğlu presented a fictional dialogue between himself and Paul Thek (the latter played by Sharjah Art Foundation’s Karmen Hassan), which proposed the late artist as a kind of patron saint for contemporary art who had sacrificed himself for a younger generation of artists. There wasn’t much conversation that morning, which was a bit of a shame for the presenters but that’s how March Meeting concluded, and people dispersed to see the parts of the Biennial they hadn’t yet, before returning home or moving on to Dubai or elsewhere.

Over the course of the Biennial’s opening days, I also visited the exhibition’s less central locations, which I haven’t discussed so far. The biggest addition to Sharjah Art Foundations is a new building intended for artist residencies in the enclave of al-Hamriyah, a Sharjah free port located north of Sharjah’s neighbor Ajman. The new building, designing by Khaled al-Najjar of the UAE firm Dxb.lab, is one story, with a large open courtyard in the center ringed by a series of concrete-floored galleries, presumably the future studios. One of the first rooms featured a trio of projects referring to the sea: Maria Thereza Alves’s wool carpets based on stamps issued by an American entrepreneur for Sharjah in the 1960s and early ‘70s that featured many American-specific references such as President John F. Kennedy and the Statue of Liberty, and images of American military and technological prowess, including those from the 1965 New York World’s Fair. The largest carpet appeared to show the coast of the emirate seen from above, which linked nicely to Marwan Rechmaoui’s nearby untitled wall pieces comprised of beeswax and concrete that meet like the shoreline or the sky and waves (“tamawuj”). This resonated formally with Walid Siti’s installation Phantom Land (2017), a massive island of plaster-covered pieces about five-centimeters high arranged in a sprawling but deformed lattice that referred as much to Mashrabiya as to unchecked urban development. Picking up the thread of Islamic architecture was an installation by Paola Yacoub, Sabil Kuttab Automate (2017), which refers to the history of Mamluk-Ottoman buildings in Cairo with a fountain (sabil) and an elementary Qu’anic school (kuttab). The central element of the piece is a plexiglass box filled with red and blue pencils that is regularly filled and drained of water, in reference to the regular flooding of the Nile and the “rising tide” offered by education itself. The Otolith Group’s two-channel installation video installation “The Third Part of the Third Measure” (2017) featured four pianists playing compositions by minimalist African-American queer composer Julian Eastman, in an ecstatically rhythmic version of what the composer called his “organic music.” The pieces were originally presented at Northwestern University and had originally created controversy among black students because of their titles—Crazy Nigger (1978), Evil Nigger (1979), and Gay Guerilla (1980)—which were removed from the recital’s program. The speech performed at the end of the video is Eastman’s response to this censorship.

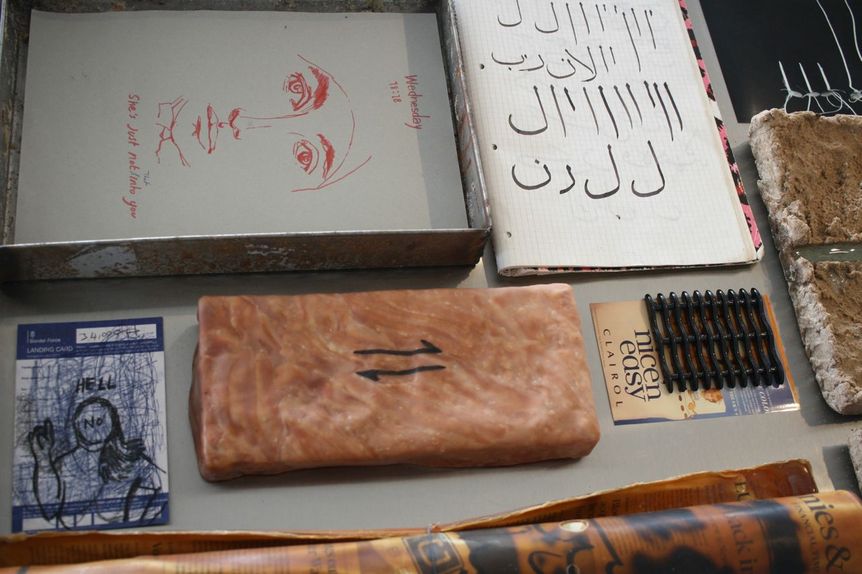

How could I not mention the Flying Saucer? Built in the late 1970s and a takeaway fried chicken restaurant (among other things) until it was utilized by the Sharjah Art Foundation for the 2015 Biennial, the domed interior has been modified and expanded for exhibitions since then (and the fried-chicken signage removed from the roof). While it was unclear what linked the seven artists’s projects here, my sense was that they all had some element of visual distortion. Daniele Genadry’s three landscape paintings in washed out colors—Light Fall, Lakelight and Blind Light (all 2017)—refer to stereoscopic imagery and early photographic attempts to create an immersive visual experience, and made the liquid component of photography and painting feel present in her partial, faded erasure of the mountain scenes. Mandy el-Sayegh’s installation, Boundary Work (2017), of two metal tabletops filled with objects coated in what looked like layers of latex, seemed to be an effort to preserve objects, and thus moments, in time, mirroring her own father’s daily calligraphic practice. Deniz Gül’s works were similarly about transformation: a bathroom sink rendered in a mute black polyurethane foam; a zigzagging neon suspended above a bed of powered sugar that looks like a city seen the air, and a garden hose rendered in plaster. Roy Samaha’s diaristic video Residue (2017) is made up of 85 GIFs from a trip from Beirut to İzmir (Turkey) and then to Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos. The GIFs playing forward and backward, mimicking the back-and-forth migrations of populations in the Aegean region, from ancient times to the present. A deconstructed smart phone, presented in a plexiglass case, like an archeological display, recalled the “tool” used by refugees today, guiding them out of Syria through Turkey to Greece and beyond. A video by Mochu, Machinic Elixir – Improvisation Two (2017) took viewers on another trans-temporal voyage, following spiritual trails forged by the 1960s counterculture through India and capturing the strange residues of hippie culture (shops filled with icon-like canvases of Jim Morrison, for example) which Mochu renders with obviously hokey visual distortions, linking the legacy of psychedelic and digital effects with the dubious search for spiritual epiphanies. It goes to a territory when post-internet aesthetics meets techno-utopianism of an earlier generation—appropriate enough for a building with a star-shaped crown, mosque-like interior dome, and brutalist concrete forms. At the Flying Saucer the “tamawuj” effect—of waves and undulations—achieved its most poetic coherence as the Biennial’s metaphor, where points on a wave (the rising and falling) connect with others points on successive waves across time and undulation. About the many still-unconnected threads from Sharjah Biennial 13, I’ll have more to say throughout the rest of the year, as the program continues in Istanbul (May 13), Ramallah (August 10) and in Beirut in mid-October.

HG Masters is editor-at-large of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.