R

E

V N

E

X

T

Portrait of TSANG KIN-WAH. Courtesy the artist and West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, Hong Kong.

Few viewers, if any, immediately relate the artwork of Tsang Kin-Wah to his Asian, Chinese or Hong Kong background just by looking at it. The artist, known for his large-scale, immersive installation works featuring primarily English-language text projections, was born into a Buddhist family but converted to Christianity after receiving his formative education at a Christian school in Hong Kong from the age of

12 to 19. According to the artist, at this point in life, he and his fellow students were taught that Christianity is the only truth and all other religions or creeds are evil.

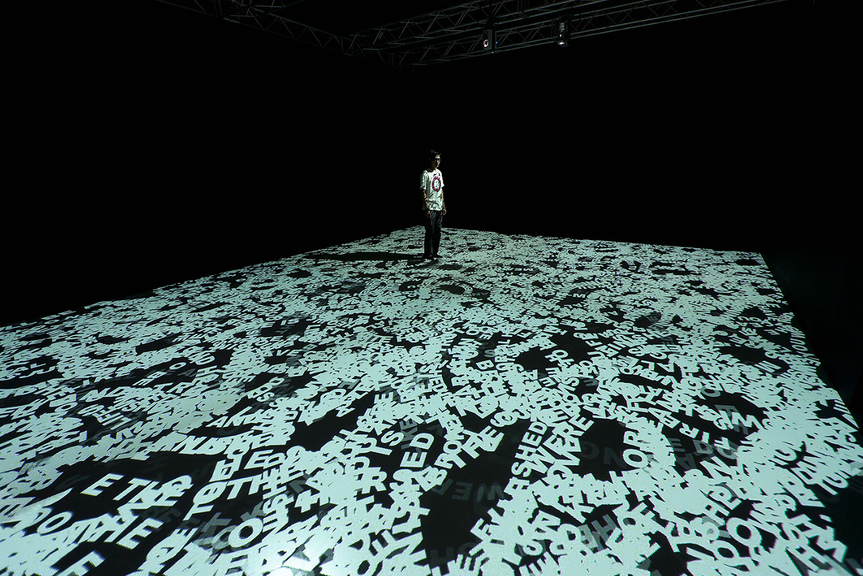

Tsang’s artistic practice has always involved texts. At the start of his career in the early 2000s, he developed the practice of covering an exhibition space with vinyl texts on the wall or the hand-drawn patterned wallpapers. The wallpapers themselves were composed of tiny words—some slang, some foul language—shaped in patterns that emulate the floral wallpaper-prints of English textile designer William Morris. In 2009, he began to create video installations—such as the immersive The Seven Seals (2009– ), Ecce Homo (2011–12) and Prelude to the Seven Bowls (2013)—in which he covered the surfaces of a darkened space with animated texts, often comprised solely

of projected words written in blocky sans-serif font. In The Second Seal – Every Being that Opposes Progress Should Be Food for You (2009), for instance, the texts read: “The sun, the horse, the sword, the man, the flood, the dead letters . . . The inclination of your heart,

the evil from your youth, and your refusal to criticize yourself . . .”

Tsang identifies himself as a resident of the “global village,” and considers himself partially British, having lived in London while

working on his Master’s degree at Camberwell College of Arts. However, although not explicitly, Tsang is probing issues of Asian identity, particularly with regard to modernization and postcolonial identity, Christian morality and its critiques. It is impossible to speak of

Asia without acknowledging the historical influence—positive and negative—of Christianity. The propagation of religion in the age of imperialism during two large-scale waves of missionary activity in East Asia—first by the Jesuits (Society of Jesus) in the 16th and 17th centuries, and the second by Catholic and Protestant organizations from the 19th century onwards—justified European hegemony. It

also served to undermine the local religious traditions of colonized territories. At the same time, Christianity greatly contributed to modernization, providing pathways for advancements in education, medicine and establishment of human rights.

Aside from his background in religious education, Tsang’s work also reference his Asian identity in another way. His solo exhibition at

Hong Kong’s M+ Pavilion in 2016, “Nothing” (2016), was an expansion of his project representing Hong Kong at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, which reflected his continuous interests in the construction of his inner world. Mirroring the formation of the artist’s psyche, the exhibition was a chaotic multitude of references, from Kurt Cobain to Taoism, the Buddhist Bodhi Tree, text extracts from the internet, Friedrich Nietzsche, Emil M. Cioran, William Shakespeare, Ludwig van Beethoven, Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, and images of trees

from Béla Tarr’s movie The Turin Horse (2011).

Upon entering the M+ exhibition, viewers passed through a mirrored corridor and walked across a floor covered with text, evoking Nietzsche’s notion of “eternal recurrence.” Inside the dimly lit space was a black-and-white projection of the prison from Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), while on the opposite side of the wall was a wide, moving image of trees, from Tarr’s film. The main black-and-white image projected onto the wide horizontal wall showed an image of leaves falling off an isolated tree in the wind, which resonated with the real tree in the courtyard. A shrine-like black box sat alone in the left corner while six aluminum-covered columns were placed between the two moving images. Four columns together—perhaps echoing the ill-fated number associated with death in Chinese culture—emulate the Aokigahara Jukai, an area near the base of Mt. Fuji known as the “forest of suicide.” Together, the projections hinted at a mythic reality or a karmic cycle of life. In both interpretations, they comprise an intimate experience, both bodily and visual.

There is also another way to think of the connection between Tsang’s works—especially those presented in “Nothing”—and contemporary Asian culture, when they are considered in relation to the tendency known as sekaikei. Translated as “world type,” sekaikei indicates a specific narrative in Japanese animation, light novels, manga and films that focus on intimate, “you and me” relationships, often set amid grandiose, apocalyptic scenarios where the survival of human race is at stake. Such stories disconnect audiences from reality, offering emotional catharsis. One of the main criticisms of the genre has been that the stories ignore the complex economic, political and historical contexts of society. Cultural critic Hiroki Azuma has suggested that these films, books and manga are often seen as “works where the excessively self-conscious leading character subjectively and speculatively links himself to ‘the end of the world,’ without considering anything regarding the society and the work.” The animated series Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–96), which is set in a dystopic, futuristic Tokyo and features gigantic cyborgs and aliens, is considered the archetypal work of sekaikei anime. The recent blockbuster Your Name (2016)—about a boy and a girl who fall in love through a body-swapping, time-traveling phenomenon, and who quickly realize that their superpower can save the lives of thousands from a comet attack—revived discussions in both Japan and its art world about the genre.

If we look at Tsang’s recent video installations, we see a private, personal interpretation of philosophy and religion that also relates to the sekaikei genre. Compared to his previous works that almost only used text, “Nothing” (2016) incorporated a number of private images, videos and music that represent Tsang’s inner world, and linked the philosophies of Buddhism and Nietzsche while not addressing the social contexts in which these worldviews exist. As these were artworks about Tsang’s personal interests, memories and his own relationship to these religious and philosophical meta-narratives, the exhibition as such could be considered more sekaikei than any of his previous works. In addition, as Tsang often mentioned in his interviews, he began utilizing philosophical and religious narratives in his practice following a separation from his girlfriend. This personal, “you and me” experience was channeled into grand narratives, making Tsang’s works even more sekaikei.

The exhibition was not only an immersive video installation, but also a construction of aesthetic space, a journey of Tsang’s inner world, and for a vast number of symbols and images. Curiously, Tsang’s personal background, his practice of using English texts about Christianity and philosophy, makes him an artist that simultaneously embodies both the position of someone growing up in postcolonial Asian culture and someone who reflects the contemporary sekaikei discourse that ignores society altogether.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.