-

From Issue 78

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Devastating History

We shall not have succeeded in demolishing everything unless we demolish the ruins as well.

Alfred Jarry

It makes for a tall tongue-twister: a Swiss artist makes an artwork of a Swiss collector dropping a Chinese antique urn that was converted into a contemporary artwork by a Chinese artist—this new Swiss artwork, in turn, becoming a parody of an artwork by that same Chinese artist of himself dropping a Chinese antique urn.

In fact, this story of unsanctioned collaboration, transformation and destruction begins much earlier in time: during the Western Han Dynasty’s (206 BCE–9 CE) age of ceramic innovation, when the vessels that are the subject of these two artworks were forged by craftsmen in kilns that have not been remembered by history. Two thousand years later, an assortment of urns were acquired by the artist and antiques connoisseur Ai Weiwei, who had just returned to Beijing after 13 years in New York City. On one urn Ai painted the Coca-Cola logo, transforming the antique vessel into a contemporary artwork. The work, Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo (1994) (known as the Coca-Cola Urn) was acquired by Uli Sigg, Switzerland’s former ambassador to Beijing and the world’s foremost collector of contemporary Chinese art. Coca-Cola Urn rapidly became one of the most prominent icons of Chinese contemporary art, a universal metaphor for the clash between consumer-driven progress and the preservation of historical artifacts.

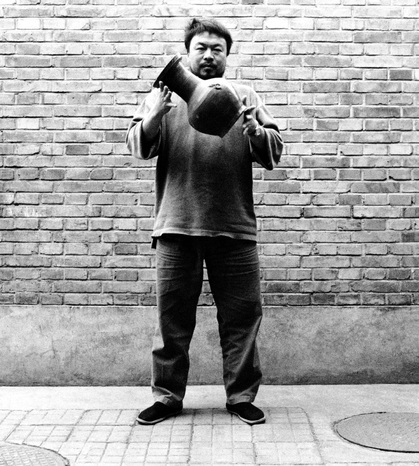

In 1995, a year after the making of Coca-Cola Urn, Ai created yet another monumental, iconoclastic work: a photographic triptych of himself holding a Han Dynasty urn, dropping it and standing over the shattered remnants. This urn was then worth a few thousand dollars, and in fact two urns, not one, were sacrificed in the making of this work, due to the failure of Ai’s photographer to capture the first urn’s fall to the ground. The triptych, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, is today perhaps Ai’s most internationally renowned photographic artwork.

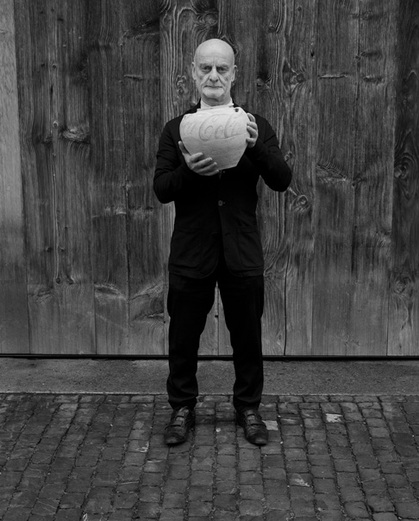

Fast-forward to 2012, when Swiss artist Manuel Salvisberg created a photographic triptych called Fragments of History, which depicts Uli Sigg in an almost identical stance to Ai’s in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Here, Sigg drops the famed Coca-Cola Urn that has long been one of the central pieces of his collection. Fragments of History is perhaps an unprecedented instance of a collector’s deliberate destruction of a valuable object in the service of a brand-new artwork, and it also refers to a long tradition of appropriation and iconoclasm in which Ai himself is well-schooled.

Fragments of History presents a singular opportunity to consider the moral rights of contemporary artists, particularly in relation to acts of artistic appropriation. “Moral rights” is a personality-based legal concept that was incorporated into French law in the late 18th century and in China by the early 20th century. In Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, a notable New York case in 1994–95, moral rights are described as “a belief that an artist in the process of creation injects his spirit into the work and that the artist’s personality as well as the integrity of the work should therefore be protected and preserved.”

The exact scope of moral rights differs by jurisdiction, but in general moral rights protect an artist’s intrinsic rights to paternity—that is, to be identified as the creator of his or her work—and to the integrity of the work, including prevention of its unauthorized alteration, mutilation or destruction. Both China and Switzerland incorporate moral rights (jingshen quanli and droit moral, respectively) into their copyright laws. Ai, as a Chinese citizen, has his moral rights protected under the Chinese Copyright Law of 1990; Salvisberg, a Swiss citizen, is subject to the Swiss Copyright Act of 1992. One major distinction between moral rights and copyright is that the former protects authors’ non-economic interests, while the latter delimits authors’ abilities to exploit other creators’ works for their financial benefit. Although the majority of lawsuits utilize copyright theory and not moral rights, there has been a renewed interest in moral rights and, in particular, much discussion about whether such personality-based rights can and should be licensed, assigned or waived.

An artist may claim that his or her moral rights are violated if their work has been altered, mutilated or destroyed without their consent. Even to the casual art viewer, a glance at Fragments of History immediately conjures the thought: did Salvisberg obtain Ai’s permission to destroy Coca-Cola Urn in the making of his work? In response to this very question, Salvisberg replied: “Did Ai Weiwei ask the masters who created the vessels he uses in his work many years ago?”

Despite Salvisberg’s dexterous answer, one assumes he probably did have the artist’s consent. If not, and if Ai believed that Coca-Cola Urn’s destruction had destroyed its integrity, Ai would likely have grounds for legal action against Salvisberg and possibly Uli Sigg, as the work’s owner and Salvisberg’s facilitator, under either Chinese or Swiss law. More realistically, one imagines that Ai, the eternal contrarian, would probably have sanctioned Salvisberg’s homage with a knowing wink.

The more intriguing questions, however, arise around the interplay and hierarchy of Salvisberg’s and Ai’s respective moral rights in Fragments of History. Assuming that Ai agreed to Coca-Cola Urn’s destruction, what moral rights does he retain in the work after its demise? Are such rights, if any, separately enforceable from Salvisberg’s? Did Ai assign certain rights to Salvisberg by implicitly licensing him to use Ai’s work?

No exact legal precedent exists for a case such as this, and the verdict would likely depend on the prevailing jurisdiction. For example, under French law, where artists’ moral rights are practically sacred, Ai could make the convincing argument that his authorization of Coca-Cola Urn’s destruction merely constitutes the further exercise of his creative expression; hence, his moral rights in the work remain perpetual and inalienable. Different outcomes might be reached in jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, which balances moral against property rights, or China, which weighs an individual’s moral rights in relation to public policy and the rights of the collective or organization involved. Alternatively, Ai could simply be denied the status of joint creator of Salvisberg’s work, and would thus lack the requisite standing to plead infringements in relation to Fragments of History.

Consider two hypothetical situations that illustrate possible conflicts of Ai’s and Salvisberg’s moral rights in Fragments of History. A Chinese magazine runs an image of Fragments of History in an opinion piece advocating that all Chinese art should be repatriated to China because foreigners don’t know how to treat it properly. The article is not satiric and correctly attributes Salvisberg as the artist and Coca-Cola Urn as “a contemporary artwork by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei.” Despite the article completely missing the point of his work, Salvisberg enjoys the publicity and doesn’t wish to take issue. Ai, on the other hand, is dismayed by his artwork being used to propagate xenophobia and considers the integrity of his work breached.

If Ai has standing to bring suit in China, an interesting precedent to consider would be that of Lin Yi v. China News Press. Lin, a photographer, successfully sued China News Press for publishing his photograph in an article exposing corruption among Chinese customs officials. Lin had intended the photograph as a piece of propaganda “praising the bravery of Chinese Customs staff,” and the court agreed that in this context both the integrity of Lin’s work, as well as his professional reputation, had suffered harm. However, given that Chinese courts frequently prioritize policy over law in their rulings, it would be surprising if a court upheld an iconoclastic artist’s intent over that of a publication with a nominally nationalist bent.

The second hypothetical scenario illustrates different outcomes in moral rights cases involving transformations of existing artwork with new technology. A third party, say, Artist X, uses advanced laser technology to create a three-dimensional, time-based light installation that transforms Salvisberg’s triptych into a hyperrealist projection of Sigg dropping Coca-Cola Urn in slow motion. If both Ai and Salvisberg sue Artist X for breaching the integrity of their works, the determination could vary depending on the jurisdiction. The estate of American filmmaker John Huston was awarded 600,000 francs in damages by a French court from Turner Entertainment, which had colorized Huston’s black-and-white film The Asphalt Jungle (1950), and the French television station La Cinq that broadcast this colorized version. Huston abhorred colorization, which he likened to “pouring 40 tablespoons of sugar water over a French roast,” and the French court agreed that Huston’s right to the integrity of his work had been breached. In contrast, Chinese courts have found that a comedian whose performance was adapted into a flash animation did not suffer infringement of his moral rights because the adaptation neither distorted nor disparaged his work. Again,

if only Ai or Salvisberg objected to Artist X’s work while the other did not, the outcomes might diverge.

When Ai created Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn and Coca-Cola Urn in the mid-1990s, both works were criticized as vandalism of cultural antiques worth thousands of dollars. Ironically, both of these contemporary works have now acquired international exposure, critical acclaim and market values far exceeding those of the original vessels. These cases illustrate the subjectivity of moral rights in relation to artistic issues of appropriation and iconoclasm, as well as the legal challenges of adjudicating moral rights in relation to public policy and technological innovation. It might be apt to conclude with DJ Enright’s poem “Vandalism,” which applies just as well to art: “Since the object in question is a modern poem, / A police spokesperson stated yesterday, / It is hard to tell whether it has been damaged / Or not or how badly.”