-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

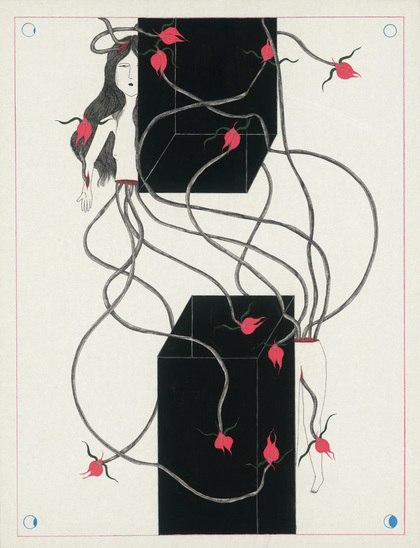

CHAN BEE, Untitled, 2020, Chinese ink, graphite, and technical pen on paper, 36.6 × 43.5 cm. All images courtesy Present Projects, Hong Kong.

Through a moon gate at Present Project’s tonglau (old low-rise tenement) space was a pen drawing of a naked woman, asleep in a floating bubble. Enlivened with colored ink, three thorny, green plants with scarlet, vulvar centers and snaking tendrils ensconce the orb, tainting the woman’s peaceful slumber with an air of imminent threat. This precarity pervaded the exhibition “Surviving Natality,” which included seven untitled works on paper (2020) by Chan Bee created in response to Chan Ho Lok’s titular collection of writings on life, death, and the perishable human body.

The artist—described in the exhibition statement as “a woman born on Earth”—transposes the book’s themes of trauma and suffering onto female-coded bodies, shown bloodied and dismembered in works suspended from the ceiling in oversize glass frames. A central motif is the violence of lifegiving, seen in an image of a bisected figure from whose bleeding stumps and genitals emerge red flowers on writhing stalks. Another piece depicts a woman impaled on a mutant rosebush, its sharp spines piercing through flesh like the arrows in classical images of Saint Sebastian, as shafts of sunlight stream through a window to illuminate her abject body and serene, upturned gaze. Chan Bee’s blossoms thrive on sacrifice.

The religious overtones—emphasized by the distorted, echoing incantations that soundtrack the show—stem from the source text, excerpts of which were printed onto the walls. Chan Ho Lok’s musings on his feelings of estrangement, as someone who has experienced depression, are folded in with spiritual perspectives on existence, including a discussion about the difference between the Christian end point of universal resurrection versus the Buddhist goal of release from cycles of rebirth. In either doctrine, the mortal body signifies a period of “stuckness,” an interim stage at the edge of a promised eternity. This entrapment is spatialized and intensified by mental disorder in Chan Ho Lok’s claustrophobic video How a Bipolar Starts the Day (2016), shot from the point of view of a person whose hands scrabble at endless light switches and door knobs in a loop.

Yet “Surviving Natality” exuded vigor, not self-defeat. Its strength lay in its ability to hold contradictions in perpetual tension, balancing suffering and survival, captivity and release. Nature, seen as menacing in the aforementioned paintings, becomes a refuge in an image of a wounded woman beneath a black, upside-down flower. The spiky plant reappears in another work, in which a one-armed, one-legged woman steps on its red gynoecium, gripping her dismembered arm in her remaining hand, while her severed leg floats further away, amid scattered black wormholes. Behind her, a tunnel yawns to reveal tentacular turquoise and tangerine stems and a rail-like frond receding toward a distant coral sun—a vibrant alternate dimension teasing at escape, rendered in brilliant hues that stand out from the sparse coloring in the rest of the composition. Likewise, contrasting geometric motifs from the paintings were transmuted to physical design elements: a black monolith seen in the image of the bisected woman appeared in a doorway, while circular mirrors beneath the hanging frames seemed to open voids in the gallery floor, materializing both blockage and rupture. A show on life’s suffering could easily have been hackneyed and tiresome, but in the imaginative whirl of “Surviving Natality,” one saw both the terror and glory of survival.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

“Surviving Natality” was on view at Present Projects, Hong Kong, from January 20 to February 20, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.