-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

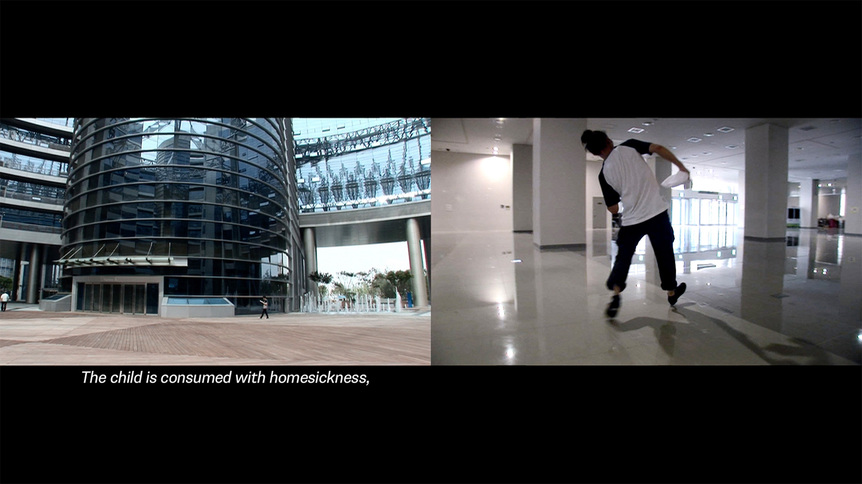

JEAMIN CHA, Fog and Smoke, 2013, still from single channel video: 20 min. Collection of Kadist. Courtesy the artist.

In Ling Ma’s postapocalyptic satire Severance (2018), those afflicted with the mysterious Shen fever fall into a trance, gradually wasting away as they mindlessly cycle through the same routines from their healthy lives. There is something unsettlingly authentic about Ma’s reinvented trope of zombie-like enslavement as an expression of capitalist malaise, and it is the author’s portrayal of drudgery within a quietly disintegrating metropolis that I think of on viewing Jeamin Cha’s “(Home)sickness.” Presented by Kadist—which has yet to open the artist’s San Francisco exhibition due to Covid-19—the online program brings together a trio of videos probing the dark underside of neoliberal modernity in Cha’s native Seoul.

Ghostliness permeates the three works, a fitting representation of the psychological dislocation felt by the invisible casualties of global capital. “There had never been a ghost in the house,” reads a woman at the beginning of Sleep Walker (2009). The two-channel video juxtaposes extended sequences of people reciting from Johanna Spyri’s novel Heidi (1881) and of a man’s frantic tap dance throughout a shopping complex that is ironically called Garden 5. The selected passages recount how Spyri’s jovial orphan starts sleepwalking upon moving from her idyllic alpine village to the city, prompting her housemates to believe they are being haunted. Cha’s performers themselves appear somnambulant, consumed with their respective activities—halfway through the video, the reader and dancer cross paths, oblivious to one another. As the screen cuts to black at the end, the sound of tapping feet continues, a frenetic coda capturing both the unceasing neurosis of city life and the relentlessness of urban encroachment.

Fog and Smoke (2013), with its dynamic camerawork and subdued symbolism, is more visually captivating. It opens to a sprawling scale model of Seoul, with light pulsing along the roads in an eerie simulation of bustling traffic. The camera tracks across a tower emblazoned with “Songdo,” locating the action in the new town on the outskirts of Seoul, before cutting to footage of a fisherman sputtering along the road on a tractor. He later recounts in a voiceover the displacement of local fishermen due to government development initiatives, as futuristic skyscrapers lining a canal fill the frames. This narrative strand intersects with footage of the city taken from a moving vehicle, and of the performer from Sleep Walker tap-dancing through empty streets. The camera is in near-constant motion, adding to the overall feeling of dislocation and exteriority; the viewer is the ghost here, hovering above construction sites and shanties. At one point, the camera pans upward from what initially appears to be a field but is actually unkempt turf next to a highway, framing a vista of skyscrapers glinting in the late-afternoon light—a sequence that foregrounds the difference between the shining there and the cheerless here. Cha disrupts the neoliberal fantasy by showing the unevenness of its promise, contrasting imagery of the new Songdo with lingering shots of the local landfill and indolent pans across dense, identikit buildings.

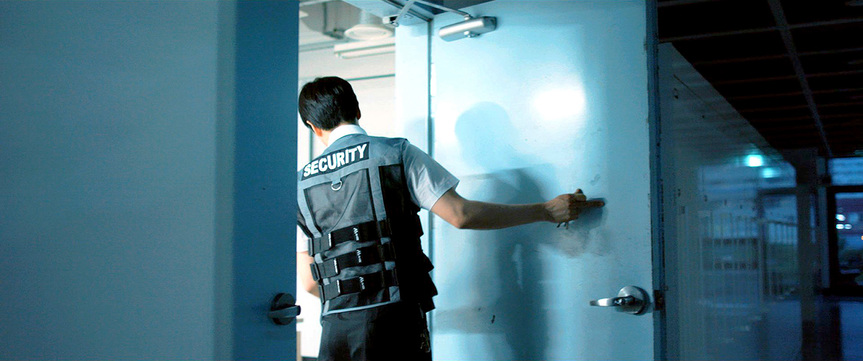

Alienation and tedium give way to more chilling disturbances in On Guard (2018), which follows a young man whose days as a warden are punctuated by his over-the-phone arrangements for someone to care for an elderly relative. This humdrum routine is laced with threat: he mechanically rehearses defensive positions in interspersed drill sequences as if preparing for imminent conflict, while objects seem to move of their own accord as the protagonist makes his rounds. The menacing scenarios occasionally evoke Stanley Kubrick’s psychological horror The Shining (1980), most noticeably in Cha’s close-up of an air mattress’s curving patterns, or spatially disorienting sequences of the guard walking through labyrinthine corridors and basements. The protagonist’s different uniforms and the scene alternations from day to night indicate temporal passage, yet he always seems to be having the same phone conversation—trapped in a cyclical grind that parallels the invisible relative’s home captivity. The drill instructor’s earlier remark that “the cost for human resources will only rise,” unlike with automated security, becomes an ominous prognosis: the protagonist will slog through his existence until he expires due to age or obsolescence.

“(Home)sickness” foregrounds those left off the neoliberal agenda, and the paradox of accepting societal ills as collateral for “economic health.” The potency of Cha’s body of work derives from an outlook it shares with Severance: The world doesn’t end in a single catastrophe; the real terror lies in the slow spiritual death that sets in long before humanity’s final gasp.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

Kadist’s “(Home)sickness” presents each of Jeamin Cha’s three videos for one week, from May 27 to June 16, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.