-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

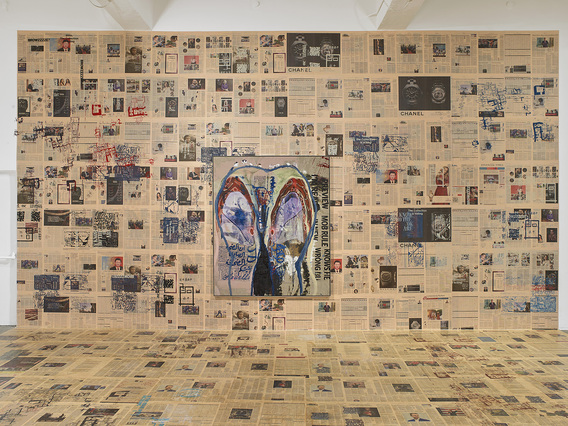

Installation view of MANDY EL-SAYEGH’s “Cite Your Sources” at Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2019. Commissioned and produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. All photos taken by Andy Keate; courtesy the artist.

“Cite Your Sources,” the title of Mandy el-Sayegh’s first solo show in the United Kingdom, presented by London’s Chisenhale Gallery, is a quote from the artist’s former tutor. It nods to the idea that a viewer’s understanding of an artwork is contingent on a multitude of influences, just as it is for the creator, and this meaning can resist being subject to clear provenance or totalizing logic. This is a tricky line to walk, as the risk with such an approach is conceptual and compositional collapse. In el-Sayegh’s case, such a calamity was avoided, but ironically thanks to what appeared to be an adherence to, followed by selective departure from, conventional artistic methods, as well as an eye for composition.

In pieces from the ongoing “Net-Grid” series (2010– ), for example, the well-established visual trope of the grid comes into play, albeit with a twist. El-Sayegh engages with the problems of painting on terms that are not so distant from the approach of Minimalism, conceiving of the canvas as a physical object onto which the application of a white, deliberately textured first layer has more significance than simply to render the surface neutral for the application of an image. On top of the first layer, the artist applies a variety of media—newspaper clippings, fragments of text, partially obscured images, and more—before painting a freehand grid in oil paint above it all. The use of the grid here evokes this particular visual device’s status as a mainstay from Modernism to Minimalism, but it also provides a literal framework in which the disparate elements of el-Sayegh’s canvases can be viewed. The motif allows a means of indexing and contextualizing the work’s elements, comparing them to each other in terms of size and position, and thereby draws connections between them and their own external associations—ultimately suggesting that our understanding of an artwork is more intertextual than intrinsic.

In the middle of the gallery was a series of stainless steel vitrine tables, each a work in itself, which provided a less ordered means of viewing disparate objects and media. The use of the clear cases evoked a sense of institutional legitimacy. This generated multiple meanings when paired with the vitrines’ contents. The array of objects on each table could feasibly create a sense of irony, even humor, in their occupying a frame most often associated with objective documentation. An alternative reading would be that this setting elevated the importance of the display. Either way, the combination of metal handles, wooden coasters, cockfight blades, old issues of Vice magazine, and more, in surefire-shut-eye (2019), or polymer clay, photographs, hair, board game packaging and kitchen toy models in Lingua-Franca (2019), makes for works that are not easily comprehended, but that have the potential for provocation by way of the frames that contain the seemingly unconnected elements, generating a symbiosis.

Not all the works were quite so difficult

to read. One of the standout points of the show, in fact, was el-Sayegh’s decision

to cover a strip of the gallery—including floor and opposing walls—with pages of the Financial Times in an installation titled Figured Ground (2019). Layered atop were various printed images from her archives—works of calligraphy by her father and uncle, diagrams of circuit boards, motifs from fashion branding, and an aerial map of a British excavation site in Gaza. Again, the artist toyed with institutional conventions and modes of framing, surrounding the works mounted within this space—such as Face Forward (2019), a mixed-media image of what appears to be a woman bent over—with an overwhelming superabundance of language and meaning, creating an effect directly opposite to that of decontextualization, often found in the white cube.

There was, besides, a hung series of mainly inkjet-on-canvas works, which brought disparate elements together in order, it seems, to create an intuitive as opposed to logical exploration of the compositions. The doughy grid and circuit-board schematics of Soft Circuit #1 (2016), and medical images of syphilis sores juxtaposed with an image of a painting hung in a gallery were, like many of the other works, difficult to extract meaning from, and yet resisted falling apart before the viewer. It is worth asking whether, putting all theorizing aside, this is in part due to the fact that el-Sayegh simply has an eye for composition, and equally worth asking whether this would be so bad.

Ned Carter Miles is ArtAsiaPacific’s London desk editor.

Mandy el-Sayegh’s “Cite Your Sources” is on view at Chisenhale Gallery, London until June 9, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.