-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of MADHVI PAREKH’s “The Curious Seeker," at DAG, New York, 2019. Photo by Marzio Fulfaro. Courtesy DAG, New York.

Outsider art—a term loosely referring to Jean Dubuffet’s description of the “raw,” childlike quality of work made by self-taught artists—came to mind on viewing Madhvi Parekh’s first survey, “The Curious Seeker,” at DAG, New York. Parekh’s introduction to art came by way of her husband, the artist Manu Parekh, who gave her Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (1924) as a present several years into their marriage. Klee’s abstract marks sparked her own depictions of childhood memories from her village in Sanjaya, Gujarat—the master painter’s dots and lines reminded Madhvi Parekh of Indian rural embroidery and ritual decorations, and initiated a deeply personal iconography of shapes for the left-handed novice.

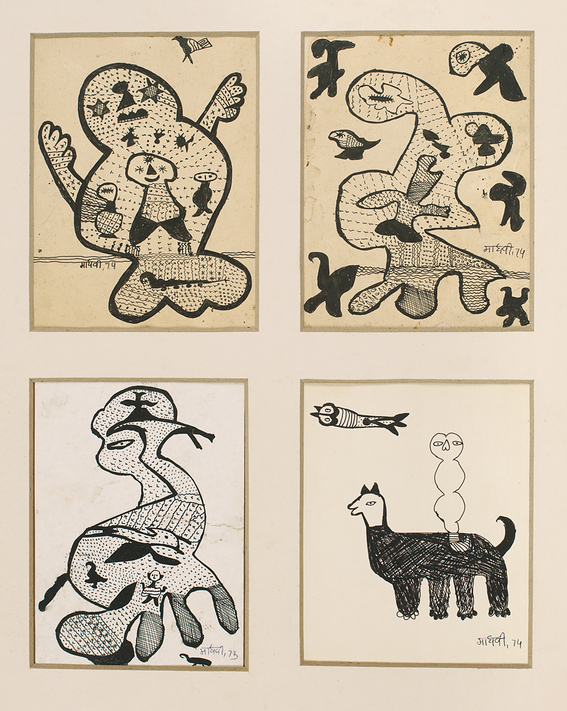

Early works from the 1960s and ’70s, made with markers and pen and ink on paper, reveal how Parekh responded to Klee’s “adventures in seeing” through her exploration of space and form. In Untitled (1974–75), large amoebic shapes embedded with small human and animal forms—now among Parekh’s signature symbols—appear to represent the cosmos. Birds and odd-looking creatures float in the air, conjuring a world imbued with the surreal and the magical. This notion is more evident in Playing under the Sea (1980), in which a human figure flanked by two bipedal beings, one resembling a scarecrow and the other bearing the head of a bird, stand peacefully under water. Always exhibiting a naïve style, Parekh’s formative abstract sketches such as Two Drawings, (Diptych) (1966), of elliptical and geometric humanoid shapes reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois’ distinctive imagery, are emblematic of her rural upbringing.

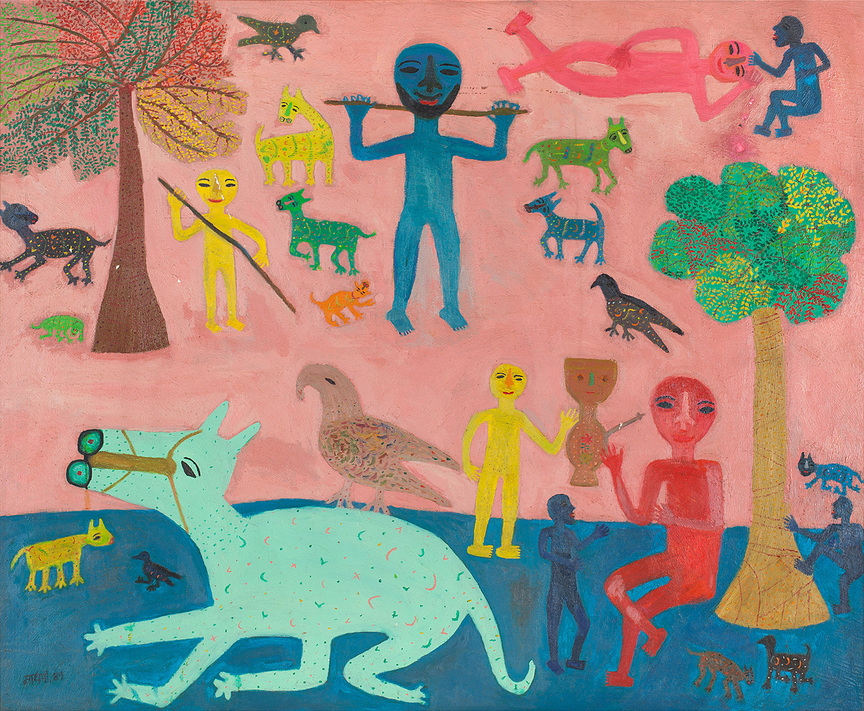

Yet unlike Bourgeois’ configurations, there is nothing unsettling about Parekh’s universe. Quite to the contrary, the latter is redolent of bucolic bliss. Paintings such as Playing with Animals (1989) and Happy in the Village (1988) point to communal harmony. There is great synchronicity between the way the depicted humans and animals interact, and synthesis in the portrayal of surrounding objects like trees, utensils, and hookahs, convincingly channeling Parekh’s desire for and vision of a temperate world. Even in paintings like Flying Goddess (1992), where airborne mythological figures from folklore clash in a battle between good and evil, the villainous human-animal hybrids look benign. More importantly, these pastoral scenes stand out for the artist’s use of color. Candy pink and teal backgrounds with painted figures in bright hues of orange, red, and yellow reflect the traditional Behrupiya folk art form that Parekh grew up with, in which performers painted their bodies in vibrant colors to playact characters from fables.

What was also immediately apparent at the show was the fluidity of Parekh’s art. Life as she recalled it unfolds on canvases where objects are rendered in complex relation to physical and intellectual space. In Sea God (1971) and Horse Rider in the Moonlight (1982), for instance, the painted shapes and symbols are interlocked and connected like totem carvings, and the figures flow effortlessly into one another. In the former, numerous life cycles of human and marine beings fill the Sea God’s organic three-legged shape; in the latter, the rider, whose extended arm seamlessly merges with a turtle’s body, is portrayed alongside a small fish inside a whale’s belly, and a child residing in a man’s heart. Parekh’s flat, non-perspectival surface propels this connectivity and mirrors the elasticity of the mind, while also alluding to the relatedness of all things in the external world.

Although some of Parekh’s later paintings are formulaic and lose the raw inventiveness of her early work, her unique interpretation of folk motifs is a constant. One might argue that her large six-panel version of Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper (2011), made by using the reverse painting technique on acrylic sheet, and Miró-esque organic shapes in works influenced by world travels remove her from the category of outsiders, who, in Dubuffet’s words, are “unscathed by artistic culture,” yet her work still vibrates for the originality of its biomorphic dreamscapes and rustic charm.

Madhvi Parekh’s “The Curious Seeker” is on view at DAG, New York, until December 6, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.