-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

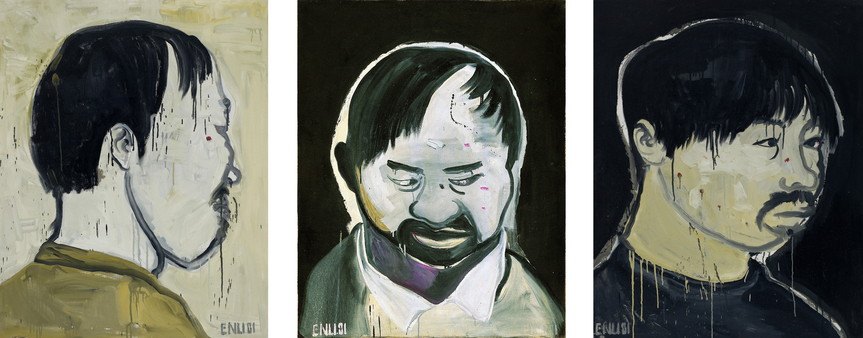

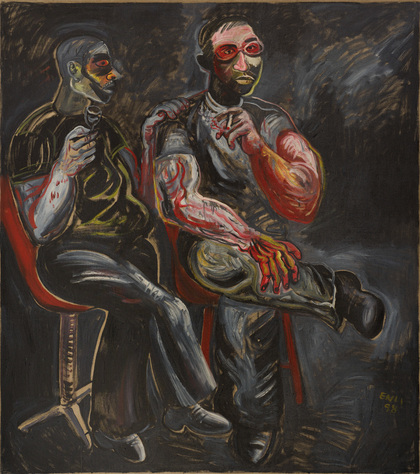

Installation view of ZHANG ENLI’s “A Room That Can Move,” at Power Station of Art (PSA), Shanghai, 2021. Courtesy PSA.

Zhang Enli’s retrospective “A Room That Can Move” presented three decades of work across two floors of the Power Station of Art (PSA). Beginning with his most recent work on the first floor, the show wound its way thematically through galleries arranged similarly to a Chinese garden, with intimate spaces enclosed by high walls and pavilion-like rooms joined by snaking paths.

Entering the exhibition, one walked under one of Zhang’s “space paintings,” large-scale works painted onto a site’s architecture or on mobile cardboard constructions—rooms that can actually move. Here, it acted as a proscenium arch ushering one into a garden of new abstractions, sizeable canvases of blotches and energetic brushwork, huddled white buds and vermillion blooms, with titles like The Meat-Eater (2019–20) and Red-faced Man (2019) conjuring the sense memories of people Zhang had once encountered.

The quietude of this illustrated garden gave way to a long hall, along which hung prosaic paintings of balls in net bags, wire coils, pipes, and torn plastic sheets. The motifs in works such as Liquid (2009) and Three Layer Plastic Sheets (2014) bear an uncanny resemblance to scholar’s rocks, traditionally admired by Chinese aesthetes for their qualities of asymmetry, thinness, openness, and complex curvature. The crowded geometries and complex lines of tubes and transparent forms display similarly alluring qualities.

The next pavilion-like space was furnished with paintings of tables and chairs, hatstands and desks. In the center, the master chamber contained three portraits of bearded men (Hair, Hair 2, and Hair, all 2001) opposite three portrait-like paintings of empty metal buckets (Bucket [ 1 ], Bucket 1, Bucket [ 7 ], all 2007), while a large painting of balls in a cage (Balls, 2007) sat at the end of the space. Zhang has referred to his still life paintings as “reflections” of people, switching subject with object. Here, it is as if we have stumbled upon the emperor, a prisoner in his own palace, surrounded by his eunuchs. The men appear to conspire while the buckets wait in solemn contemplation, as empty vessels are wont to do. The juxtaposition of images compounded the sense of interloping in a private estate.

Leaving the central space, one passed more images of furniture, vacant rooms, and empty containers before entering a smaller room populated by earlier, figurative paintings of townsfolk eating, sleeping, and bathing. These led on to the back street, thronging with dancers and revellers from Zhang’s Pub series of the late 1990s, and among the Old Butcher works, evoking the stench and blood of market stalls.

Upstairs, the gallery implied a different psychological and physical setting entirely. Absent of partitions and small rooms, one found large open spaces, only interrupted by painted columns and a central cardboard construction recalling the Empire State Building in New York. If the downstairs galleries were the provincial governor’s garden, this was the modern city. Fittingly, these rooms contained Zhang’s most recent works: buttery abstractions, and paintings of tiled surfaces and loopy reels of insulated wire, familiar to any modern Chinese city. While the paintings of his earlier years reflected the quotidian lives and effects of old China, these speak to the ungainly but essential materials that make up an emerging power, the cables that carry gigawatts and terabytes.

Set apart from these thematic areas were the space paintings, especially created for the exhibition. Zhang has been developing this practice since 2010 from a desire to eschew the tedium of a mature painting technique in favor of a spontaneous, authentic approach and the immediacy of working directly on walls. Yet extending this practice to pre-painted cardboard boxes for this show undermined this sense of immediacy and spontaneity. Further, the mark-making felt rushed, inexpert, and at moments incomplete—a small purpose-built corridor seemed almost untouched while a transparent tent structure with two spray-painted daubs on the museum’s rooftop terrace appeared unfinished. A Room That Can Move had content enough without them, and would have been stronger for their absence.

Hutch Wilco is ArtAsiaPacific’s Shanghai desk editor.

Zhang Enli’s “A Room That Can Move” was on view at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai, from November 7, 2020, to March 7, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.